Most of us go through life happily discovering composers

who are new to us personally but whose music already has a following.

We meet these men ó and women ó at various times and add their works

to our collections. We are able to read about them and their achievements

either in full-length biographies, articles in journals or in reference

books. Occasionally a researcher finds the manuscript of an unknown

or lost work by a known composer such as the Berlioz Messe Solennelle

as recently as 1992.

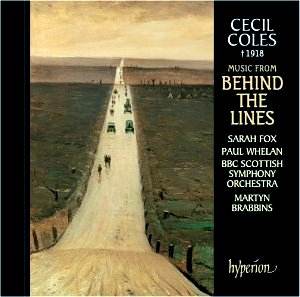

But I cannot recall any case that parallels the dramatic

and poignant discovery of Cecil Coles, the Scottish composer who vanished

without a trace from the musical world despite his friendship with Gustav

Holst and the critical acclaim that followed performances of his music

prior to the Great War.

Like George Butterworth, Frederic Kelly, Ernest Farrar

and Denis Browne, Coles died in the Great War but unlike them he had

no committed champions to keep his name alive and his music before the

public. Now, 84 years after his death, his star is rising thanks to

the combined efforts of his daughter, Penny Catherine Coles, who never

knew her father, conductor Martyn Brabbins and Ted Perry at Hyperion

Records.

After Colesí death on 26 April 1918, his widow refused

to talk about him and eventually, for reasons unknown, the family became

estranged. It wasnít until ten years ago when Catherineís elder brother

Brooke was dying that he contacted her and told her about their fatherís

life and his music. Miss Coles, a writer then in her mid-seventies,

located her fatherís manuscripts at George Watsonís College in Edinburgh,

where Coles had studied. After overcoming some legal hurdles, she deposited

the music, some of it stained with mud and blood and shrapnel-pocked,

at the National Library of Scotland. Indeed two movements of the suite

Behind the Lines are presumed (by Holst) to have been destroyed

by a shell in March 1918.

In 1995, BBC Radio Scotland introduced Coles music

and his daughter to audiences in its Remembrance Sunday program. Four

years later, Brabbins and the BBC SSO performed Coles orchestral music

in a Studio One Concert and in December 2001, four more orchestral works

were introduced. One critic hailed the performances as "an evening

of startling revelations".

Brabbins, who completed the orchestration of one of

the two surviving movements of Behind the Lines, believes that

Coles "was clearly a huge talent cut down in its prime". Brabbins,

the BBC SSO and soloists Fox and Whelan serve Coles very well in this

revealing premiere recording.

While it might be easy to compare him with the composers

whose influences are apparent in his music ó Elgar, Wagner, Mahler,

Brahms and others ó I find such comparisons a bit unfair. Coles was

a young man when he died - only 29. The amount of music he left is small

and much of it is the work of a developing composer who did not have

the time he needed to find a voice that was fully his own. This in no

way diminishes his achievement which is quite remarkable given that

some of the music on this CD dates from his teens. Consider the music

that Elgar, Vaughan Williams, Holst composed at the ages of 17, 21,

23, 26 and 29, measure their musical growth, look at the influences

and opportunities that helped them shape their work and find their own

voices. What would the legacy of each be if he had died at 29?

Coles was a passionate man with a gift for dramatic

expression and scene painting, a musical explorer who embarked on an

adventure each time he put notes on paper. He absorbed sensations and

ideas and observed and captured beauty with the confidence, daring and

purpose of a gifted and determined young man poised to soar.

Coles was essentially a poet, dramatist and painter

working in the medium of music. His profound poetic sensibility drove

his major gift for writing vocal works. He used an orchestral palette

of wide range, depth and nuance to paint evocative scenes and portray

human drama. Even as a teenager, he possessed an innate ability to capture

the right color, tone and emotion in his compositions. The spontaneous,

natural and compelling flow of Colesí music transcends technical accomplishment

and his ideas flow effortlessly and lyrically.

He must have experienced great joy and satisfaction

composing his music, experimenting and learning as he went along. Even

early works like the three-movement From the Scottish Highlands,

a work he began at 17, have a richness and character that is not forced.

He had had little musical training by this time so his ability to handle

the orchestra with considerable assurance is all the more notable. He

was like a sponge absorbing technique, using the music and composers

he already knew as guides and teachers to help him shape his composition.

The Highlands brood and dance in shadows and shafts of light while Coles,

the observer, renders an impression of landscape, love and something

darker, more elusive and mysterious in the beautiful but lonely Highlands.

Coles completed the Four Verlaine Songs in 1909

in Stuttgart, Germany, where he had gone to study on a scholarship (Coles

had previously studied music at Edinburgh University and the London

College of Music). Here we have the first hint of an opera composer

in the making. He sets scenes, contrasts moods and casts words to powerful

effect with the orchestra surging and swelling as a sumptuous equal

partner to create four brief episodes of a mini-drama. Coles had an

instinctive feeling for the meaning and intent of words and weighed

their value carefully before he set them. His music always seems to

fit or express what the words say. "Letís dance the jig",

the last song in the set, is a small gem with its flamboyant introduction

that tumbles into a loverís lament. The structure, daring and colour

of "Letís dance the jig" suggest more than a concluding song

in a cycle but serve as a hint of things yet to come from a bold and

adventurous young composer.

The Scherzo and Overture: The Comedy of Errors

are also early works dating from Colesí twenty-first and twenty-third

years. The overture contains, as Dr. Jeremy Dibble observes in his excellent

discussion of the music, a "broad spectrum of emotions" which

Coles expresses with confidence, warmth, vigour, playfulness and, at

times, majesty. The Scherzo, possibly conceived as a movement

for a symphony, stands on its own as a work that sustains its momentum

and remains dynamic from beginning to end. Coles never falters nor does

he meander uncertainly into flat space to search for ways to connect

musical thoughts. He displays confidence throughout. The Scherzo

remains alive, vital, and varied with Colesí own enthusiasm keeping

the listener alert and anticipating what comes next.

Fra Giacomo, a monologue or scena, for

baritone and orchestra, is an intense and masterful work bathed in a

chiaroscuro of sound and mood that is both tender and chilling. It is

a dark psychological tale of infidelity, jealousy, murder and revenge,

which the 25-year-old Coles handles with insight and sensitivity. Coles

was in full control of his orchestral palette and he used it to dramatic

effect. The words "Ay Father, let us go down! But first, if it

please you, your blessing." seem innocent enough following the

disclosure that the speakerís wife has died but they are underscored

by orchestral tones that warn of an ominous turn in the story. Coles

turns the line "As I kiss her on the cheek" into a sensual

caress while at the same time allowing the husband a moment of quiet

reflection before he takes the next step in his deadly plan. There are

many beautiful, moving and tense moments in Fra Giacomo as Coles

musically juxtaposes the characterís thoughts and actions to achieve

exactly the right effect and emotional response.

Behind the Lines, the title work, concludes

this superb introduction to Coles. It is half of the full composition

that Coles composed and scored while he was "In the Field"

of war. He carried the manuscript with him everywhere and as a result

lost the two inner movements in the shelling. On the stained title page,

he lists all four movements: "Estaminet du Carrefour", "The

Wayside Shrine", "Rumours" and "Cortège".

What makes this work remarkable is the fact that the "Estaminet

du Carrefour" and "Cortège" are the musical equivalent

of todayís live coverage of an event. The only other orchestral work

of which I am aware that was actually composed during the war is Frederic

Kellyís Elegy for Strings to the memory of Rupert Brooke. Kelly,

who died in 1916, began the work the day after Brookeís burial on Skyros

in April 1915.

In Behind the Lines, Coles depicts two subjects

that all soldiers knew: the lightness and freedom of being on rest away

from the battlefields, enjoying the quiet countryside and the conviviality

of the estaminet or café in a village. And the more somber side

of war: death, not the immediate horror of it but the aftermath rendered

in a scene of the ceremonial cortège known to all soldiers. The

music is solemn, poignant and majestic in conductor Brabbinsí orchestration.

Coles did not live long enough to complete Behind the Lines.

He died on 26 April 1918 of wounds received when he volunteered to bring

in casualties from a wood.

A genius? Yes, I think so. A great loss to music? Absolutely.

Pamela Blevins

Ian Lace has also listened to this disc

The manuscript of Behind the Lines is spattered with blood and mud.

Cecil Coles was killed near the Somme on 26th August 1918 during a heroic

attempt to rescue some wounded comrades. He was in his 29th year. The

Great War took its toll on many British composers: it also snatched

the lives of Ernest Farrar and George Butterworth and seared those of

others like Arthur Bliss (composer of the film score of Things To Come),

Ivor Gurney, E.J. Moeran and Patrick Hadley. But the life and work of

Cecil Coles has until now lain all but forgotten. However, thanks to

the persistence and research of his daughter, Penny Catherine Coles,

his manuscripts, some embedded with shrapnel, have been painstakingly

put together to create this first commercial recording of these works

(or indeed of any of his music!).

Behind the Lines consists of a short pastoral evocation ('Estaminet

du Carrefour' - coffee house or tavern at the crossroads) of northern

French landscapes with a central waltz that might have been heard at

a local town dance and, more importantly, 'Cortège', a moving

evocation of a military funeral procession - one of many that Coles

must have witnessed in those grim days.

Coles's music shows influences of Wagner, Bruckner, Brahms and Richard

Strauss. It is powerful and intensely dramatic and atmospheric. There

is much programme music here. Perhaps the most impressive work is Fra

Giacomo a setting of some macabre verses by Robert Williams Buchanan.

It is a tale of revenge and murder and Coles seizes every opportunity

to colour and accentuate its melodrama. A merchant invites the monk,

Fra Giacomo to pray over the body of his newly deceased wife. It soon

becomes clear that the merchant had suspected his wife of infidelity.

Donning the disguise of a priest, he discovered, from her confessions,

that the guilty one was none other than Fra Giacomo to whom he now confesses

that he had not only poisoned his wife but also the drink that the monk

was at that moment quaffing. The work ends with the merchant dumping

the body of the guilty monk in the canal. Baritone Paul Whelan and Brabbins

interpret these murky proceedings with relish.

Coles was interested in French poetry and the chansons of Fauré,

Chausson, Debussy and Ravel. His imaginative and impressive Four Verlaine

Songs combine the elegance and refinement of French mélodies

with a more darkly trenchant Germanic influence. 'Fantastic in Appearance'

is a somewhat harrowing picture of a river gliding 'like death swells…'

through a town. 'A slumber vast and black', is an intensely despairing

song of lost love is written in a progressive post-Wagnerian style while

'Let's dance the jig' is a more defiant and stoical acceptance of lost

love with Sarah Fox savouring its irony. 'Pastorale', is the sunniest

song of the set, a quietly bucolic little piece.

The Comedy of Errors Overture, from Shakespeare's play of misunderstandings,

mistaken identities and reversals of fortune, covers a broad spectrum

of emotions from a darkly turbulent opening, signifying despair to lyrical

romantic episodes and comic burlesque. Influences are many and varied

from Mendelssohn to Wagner and Mahler by way of Edward German and even

a hint of Eric Coates! - but assembled convincingly and entertainingly.

The satirical Scherzo in A minor is another evocative work in a similar

vein. It is full of sardonic humour with, in parts, a demonic edge and

Coles introduces some arresting harmonies and orchestrations. Occasionally,

its rhythms might imply a Spanish setting. From the Scottish Highlands

comprises a Mendelssohnian Prelude with a bolero-like dance. The central

Idyll (Love scene) is unashamedly romantic; akin to Bruch or Tchaikovsky

in its lusher moments while the concluding Lament broods darkly and

menacingly although its trio is a tender waltz.

In truth, Cecil Coles's music cannot be claimed to be a major find

for it is the work of a young man yet to establish his own voice. It

is often derivative and thematically none too strong. But it demonstrates

Coles's penchant for the dramatic and a gift for writing evocative,

atmospheric music. Like George Butterworth, who also died at the Battle

of the Somme, he showed great promise. A notable find and a valuable

addition to the British music archives. Hyperion and Martyn Brabbins,

who contributed to the restoration of this music, are to be congratulated

on the release of this enterprising album.

Ian Lace