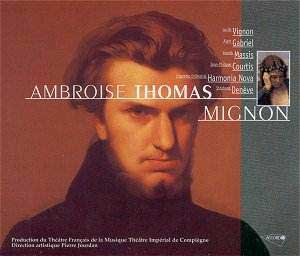

A hundred years ago anybody would have told you that

the top three French operas were Carmen, Faust and Mignon.

(Massenet was just getting into his stride and only a madman would have

supposed that an opera by Berlioz was a viable concern). Indeed, statistics

show Mignon to have been the most popular of the three, reaching

its 1,000th performance in 28 years (Carmen took 29,

Faust 35). By 1955 it had chalked up 2,000 performances but by

then its star was waning. While Carmen is surely established

among the immortals and Faust has resisted a good deal of critical

snobbery, Mignon has not often been heard in recent years and

even its once-famous romance "Connais-tu le pays" is now more

of a diploma set-piece than a recitalist’s standby. This melody, which

also concludes the opera, is already heard in the Prelude, played here

with a lethargy which arouses fears for the aria itself that prove only

too well founded.

The present performance is taken from a production

at Compiègne in 1996 and is the first on CD. However, by one

of those coincidences of which only prima donnas and recording companies

are capable, Sony Classical have just remembered that they have a performance

rusting away in their vaults recorded in London in 1978 under Antonio

de Almeida with Marilyn Horne in the title role and the other major

parts taken by Ruth Welting, Alain Vanzo, Nicola Zaccaria and Frederica

von Stade. The scholarly Almeida included alternative versions of the

beginning of Act Two and the finale and his four LPs, timed at 194’

55", occupy three CDs. Since the present 2-CD issue is not exactly

ideal, readers are advised to seek further information about the Sony

reissue, which I have not heard yet, before deciding which to buy.

The Almeida was the first complete recording of the

opera (a live recording dating from 1949, made in Mexico and sung in

Italian with a little-known Mignon, Graciela Milera, but counting Di

Stefano, Siepi and the young Simionato among the cast, is presumably

for specialists only). However, two LPs containing substantial extracts

were issued during the 1960s, one on HMV with Rhodes, Esposito, Vanzo

and Roux under Hartemann, the other on Deutsche Grammophon with Berbié,

Mesplé, Dunan and Depraz under Jean Fournet. Again, I haven’t

heard either of them but they must surely enshrine many of the traditional

French operatic values and I hope they will resurface one day. Of modern

artists, Susan Graham performed the role in Toulouse in 2002. A revival

is planned for 2005 so a recording from that source seems unlikely in

the immediate future.

Could Mignon ever regain its former popularity?

Probably not. My reaction to the first act was that there was a lot

less real music than there is in either Carmen or Faust;

many pages of agreeably-shaped recitative, supported by some pleasant

orchestral colours. Thomas certainly shows great skill in maintaining

the identity of his characters in quite elaborate ensembles – such as

the sextet – but choruses and dance music are conventional and unmemorable

compared with Bizet or Gounod. However, I found the level of interest

rose considerably in the second and third acts – partly because of the

story itself, but arias and other set pieces for the various characters

come more frequently. As well as her Act One romance, Mignon has an

entertaining scene in Act Two in which she experiments with Philine’s

make-up box and both Wilhelm Meister and Lothario have arias of melancholy

sweetness to match Mignon’s own. Once again, Thomas shows skill in contrasting

his mezzo-soprano heroine with a light coloratura soprano, the frivolous

and spiteful Philine. There is a tendency, though, for the lighter music,

such as the gavotte, to sound more conventional than the slower numbers.

One question which the detailed booklet notes do not address is why

the role of Frédéric, sung as a breeches role (by von

Stade) under Almeida, and I believe normally so performed, is taken

here by a tenor. In short, Mignon is not really on the same level

as either Carmen or Faust, but its total eclipse seems

unfair. Truth to tell, though, I think it was eclipsed not so much by

Carmen and Faust as by Werther. Placing the two

melancholy Goethe-derived heroines side-by-side there is no doubt which

makes the stronger impression, as well as being closer to the spirit

of Goethe, and surely any mezzo-soprano, given the choice, would rather

sing Charlotte than Mignon.

The booklet gives a lot of information about both the

composer and the opera, in three languages (but the synopsis and libretto

are in French only). It discusses the various versions of the opera

at some length, without actually stating what we are going to hear on

the CDs. It is the grand opera version (recitatives not dialogue) with

the happy ending (Thomas’s tendency to provide happy endings to great

literary tragedies was also a notable characteristic of his version

of Hamlet). Applause is included at the end of each act but the only

other evidence of an audience is a few titters as Mignon re-enters in

the second act dolled up in one of Philine’s dresses. There are the

inevitable bangs and bumps associated with live performances. The recording

has been transferred at a low level, but even increasing my volume control

did not remove the impression that a veil had been cast between me and

the music. This in its turn exacerbates a sense of pallor which derives

principally from the conductor. I have mentioned the slow tempo for

"Connais-tu?" – it’s marked andante not adagio – and at the

beginning of Act Three he seems to be trying to see how slow it is possible

to go without actually stopping. Even when the livelier tempi are fast

enough, there is little sense of rhythmic bite. The lack of an incisive

presence on the podium probably accounts for a general lack of sharp

characterisation on the part of the singers. Just to give one example,

Frédéric’s brief exchange with Laërte and Wilhelm

(CD1, towards the end of track 13), where his exclamation "Cursed

Baron, cursed message, cursed coquette" would seem to imply something

more than a placid delivery; nor does he sound "severe" when

he addresses Wilhelm.

The best of the singers is Annick Massis as Philine.

She negotiates her coloratura with considerable ease and her high notes

are relaxed and musical. Alain Gabriel, as Meister, is attractive, plangent

and sensitive in the middle range but his high notes are forced. Jean-Philippe

Courtis sounds old enough for the part of Lothario but this sort of

"realistic" casting (like a Violetta or a Mimì with

a hacking cough from beginning to end) is not really what opera is about.

His crooning delivery of the Act Three lullaby is effective microphone

singing; I just hope the public in the theatre heard it. The problem

of the role of Mignon is that a certain type of mezzo-soprano is likely

to sound far too substantial and matronly for such a frail young creature.

This is at times the problem with Lucile Vignon’s otherwise sensitive

performance. It is not really her fault – a "light" mezzo

such as von Otter is what the role requires. Her several G sharps in

the final ensemble are rather sharp.

She also raises another query, regarding that snorty

French "r", the bane of our schoolboy existence as we turned

our tongues and our throats inside out in attempt to master it. You

may have noticed that French singers generally sing a normal trilled

"r" as in Italian or even in English (though only the Scots

and Irish use it regularly in the spoken language). And in fact the

great Pierre Bernac decreed that in singing this snorty "r"

is sometimes used in folksong and cabaret, but in classical opera and

mélodie its use is to be considered vulgar. It is no business

of mine to tell the French how to sing their own language, so I limit

myself to pointing out that, while all the other singers here evidently

agree with the great Pierre Bernac, Vignon frequently does not.

The booklet concludes with copious notes (in French

only) about not only the performers but also about a number of people

who are not actually heard on the recording at all, such as the pianist,

the director of musical studies (the remarkable Irène Aïtoff,

then 92 years of age) and, with almost two whole pages clearly the most

important person present, the Artistic Director Pierre Jourdan. We get

a chronological list of his productions from 1968 to 1997. The prompter

is neither heard (fortunately) nor named, and what about the ushers,

the programme-sellers and the barmen? Seriously, perhaps we are inclined

to ignore, in recording credits, a whole string of names who have contributed

to the final result although they are not actually heard on the recording.

However, in this particular case the failure to rise above a decent

provincial level must be laid at somebody’s door, and since the Artistic

Director has seen that his name is well in evidence, I take it he is

ready to respond in first person for any artistic shortcomings there

may be.

If this were the only recording I would be prepared

to say that it gives a reasonable idea of the work. As it is, I can

only suggest holding on to see what the Sony reissue has to offer.

Christopher Howell