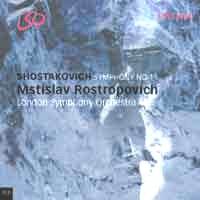

This stunning performance of Shostakovich’s Symphony

No. 11 was recorded live at a series of concerts in London to celebrate

Rostropovich’s 75th birthday last March. Conducting works

by composers Rostropovich had known (Britten, Prokofiev and Shostakovich)

all the concerts were notable for the intensity of the playing and the

incandescence of the conductor, perhaps now at the zenith of his interpretative

skills.

The Shostakovich was ecstatically received by London’s

critics, and Rostropovich was given a standing ovation after the first

concert performance of the symphony. How odd, therefore, that LSO Live

should remove applause, which they had the misfortune to leave intact

in their recording of Elgar’s First Symphony under Colin Davis, a much

less notable recording than this one. If any recent live performance

justifies the inclusion of applause it is this Shostakovich Eleventh,

a helter-skelter of emotion and intensity.

The symphony is neither one of the composer’s best

(suffering from the same bombast that disfigures the Twelfth) nor one

of his most heard in the concert hall. Partly for that reason it is

easier to be persuaded by the sheer bravura of this performance; ones

of the Fifth, Eighth and Tenth nowadays lack the very quality this recording

has in spades: a sense of newness, and a sense of rawness to the playing

it is rare to hear from Western orchestras. Some years ago Bernard Haitink

conducted two performances of the Eighth with the London Symphony Orchestra

which, because they were so perfectly and so beautifully played, left

this writer quite unmoved. That symphony simply cannot be played like

that and actually mean anything. Rostropovich is a different animal

altogether; the playing is superlative throughout, but there is a volcanic

power underpinning an interpretation of wild dynamic extremes. Only

a truly great orchestra can play pianissimos with the ghostly

restlessness we hear in the opening movement (piano playing that

has a kaleidoscope of inner-meaning to it); at the other extreme, such

as the brass band fanfares in the second movement, only a truly great

conductor can open up the multitude of textures so every instrument

is given an inner clarity. Orchestra and conductor work together in

such a symbiotic way that this recording actually seems the more remarkable

for it.

The Eleventh is contemporaneous with events in Hungary

in 1956, yet, like all of Shostakovich’s symphonies after the Fourth,

the work seems to invite universal truths into its interpretations and

interpreters. Few conductors are more crushing in the climaxes of this

work than Rostropovich, and even fewer are as tender in the more eerily

quiet sections of the symphony. Rostropovich’s interpretation is based

on a broad latitude of suffering most conductors simply do not bring

to the symphonies of Shostakovich, and this is the very reason this

particular performance can only be compared with the very greatest:

Mravinsky in Prague in 1967 (available on Praga PR 254018) and in Leningrad

in 1957 (on Russian Disc RDCD 11157).

The symphony must be a nightmare to record live, given

that the balances are so extreme in the work. The LSO engineers do not

entirely succeed – in the final movement from about 6’00 to 7’46 the

sound seems congested, and the strings sound almost metallic and slightly

grate on the ear. Moreover, playback needs to be at a very high volume

to produce sufficient bass in the recording, a real problem when the

dynamics of the work are so broadly based. When this performance is

loud it is very loud; when it is quiet it is almost inaudible.