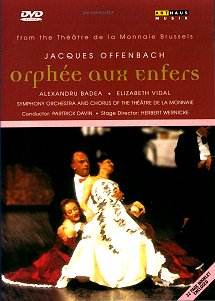

Satire is a funny game. Offenbach’s parody of Napoleonic

society and its social injustices uses figures from Classical mythology

to render the comedy and comment at one remove, a trick pioneered by

Aristophanes and used frequently during the intervening space of (approximately)

2368 years. Orphée’s success led Napoleon himself to order a

Command Performance of the piece 18 months later, which is rather like

The Queen inviting the Sex Pistols to a Royal Variety Show.

The tableau gradually revealed during the Overture

leads the viewer to suppose that a recognisable reflection of that satiric

intent is about to unfold: Classical scenes of disporting deities are

revealed, but there’s something wrong: the paintings are third-rate,

and they are peeling off the walls. This is a nice idea which puts the

viewer in house and distracts from the scrappy playing and sluggish

conducting in the pit, where the camera is usually trained during these

opera-on-film productions.

The Bizarreries only start when Public Opinion is revealed

not on stage but haranguing her way through the stalls, a French Nora

Batty in appearance and vocal quality. If it’s put on, it still sounds

dreadful. The production’s one estimable advantage soon appears, an

Orpheus who can actually play the fiddle as opposed to the lame mugging

often seen on stage. In fact Badea’s skills on the violin are superior

to those of his voice, which proves dry and rather inflexible. Mind

you, one can only sympathise when Eurydice, driven to despair by her

husband’s violinistic soliloquies, exclaims ‘Ah, how dreary and irritating!’

The fault here lies less with Orpheus or Badea than with Offenbach,

in one of the several musically thin moments (sometimes five-minute

spans) in the piece.

But there’s also fizz and fun in Offenbach’s score,

so long as the conductor and director are willing to share the joke.

They aren’t here. Tempos stay flat, and when they speed up from time

to time, cracks show in the ensemble large enough to demonstrate why

they slow down again. Act 2 is set on Mount Olympus but in Herbert Wernicke’s

vision, the gods loll about in the ‘Mort Subite’ café, wherein

the action of the whole opera takes place. Perhaps the geographical

transference pokes fun at the dinner-jacketed and degenerate upper classes

(even those who go to the opera, bit of cutting social criticism there)

of our age and of Offenbach’s. I thought, perhaps naively, that one

of the first rules of drama was that the characters have to appear interested

in what they are doing for the audience to share the feeling. Everyone

looks so catatonically bored that it required an effort of will not

to put them out of their misery and press the ‘Eject’ button. Maybe

the entry of Mercury, winged messenger of the gods, through the café

roof was meant to reduce me to helpless laughter, or maybe it was his

continual failure to sing on the beat. Constant stage business renders

absurd the few moments of lyric tenderness; while Eurydice sings her

farewell to earth, Pluto slathers on panstick to make himself up as

a comedy devil. Orpheus’s brief song of triumph is subverted by Public

Opinion stumbling along the front row of the stalls and treading on

the toes of a few Brussels opera-goers en route. It’s not funny, and

it has precious little to do with Offenbach. In such circumstances it’s

no wonder there are no very distinguished vocal contributions, though

Elisabeth Vidal’s Eurydice is brightly sung. The opera’s famous closing

Can-Can bowls along, as it should, with a slight sense of hysteria that

suggests either another po-mo piece of subversion or relief on the performers’

part that they have got this far.

May I suggest that the senses of humour possessed by

the French and the Germans are not entirely complementary? My apologies

to those who regard such comment as a slur on either nation, but I posit

it as one possible reason among many to account for this turgid travesty

of a night at the Brussels Opera.

Peter Quantrill