Prague born Ignaz Moscheles grew to maturity as a young

virtuoso alongside such contemporary titans as Hummel, Cramer and Weber.

Venerating Mozart and Clementi he lived to see the adulation of the

Liszt cult and it’s perhaps tempting to see Moscheles as a locus classicus

of the early romantic dilemma – inheritor of Mozartian procedures but

straining to encompass a wider body of expression. In that of course

he was not alone – and I think it would be fair to say that he succeeded

far more comprehensively and more persuasively in his solo piano works

than in his concertos. He apparently admitted that he found problems

with the orchestration of the Concertos, though there is certainly nothing

either improper or limited in a conventional sense about the carapace

he placed around the solo part. But there is, ultimately, a lack of

melodic distinction to these works that render them peripheral to the

struggles of the early romantic literature, though not, obviously, without

moments of interest.

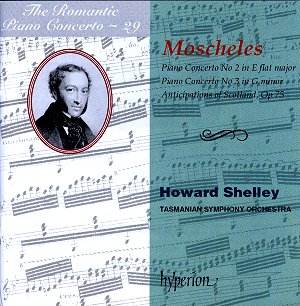

Moscheles wrote eight Piano concertos between 1819-38.

The Third is the best known and has been recorded several times before.

It’s a strong, powerful work that struggles to balance Classical equilibrium

with more subjective Romantic elements. The maintenance of such dichotomous

material was inherently problematical, though it has to be said that

Moscheles’ acknowledgment of it was implicit in his scores and it’s

a welcome sign of his imaginative engagement that he was prepared to

attempt the coalescence of such material in his writing. To the Mozartian

frame Moscheles looked to Beethovenian propulsion. This added a determined

syntax to the development of the First Movement of the Third Concerto

which still manages to breathe effortlessly. The slow movement’s brass

interjections and thematically rather theatrical gestures lead to the

piano’s scampering insouciance; Moscheles floods the movement with lightness

and a measured largesse of spirit but is reluctant ever to plumb great

fissures of feeling. He remains an urbane cosmopolitan when it comes

to depth. In the earlier Concerto, published in 1825 but first performed

some years previously his Mozartian proprieties are fleshed out orchestrally,

extended but never inflated. Throughout the first movement elements

of Polonaise rhythm threaten to become explicit and the anticipation

of Chopin is palpable here; it wasn’t only Field and Hummel who occupied

some amorphous proto-Chopinesque territory. Again Moscheles’ slow movement

is a decorative and rather frilly one whilst the dotted noted finale

makes clear what the first movement hinted at – a Polish dance movement.

The grandiloquently titled Anticipations of Scotland; A Grand Fantasia

was written when Moscheles lived in England – as he did for over twenty

years; playful, frequently variational in form, employing the expected

dance rhythms. Performances are good; sometimes the strings sound undernourished

in the Concertos. Not a disc of undiscovered masterpieces obviously

but a sure reflection of the dilemmas confronting a talented composer,

thematically and stylistically, during two decades of the early nineteenth

century.

Jonathan Woolf

Hyperion

Romantic Piano Concerto Series