Martin is not a crowd-pleaser. Had he been born in

the UK he would have been viewed as part of the benighted Cheltenham

generation. Performances in Cheltenham would have been in the 1940s

and 1950s but as the 1970s progressed he and his music would have lost

its precarious footing and slipped from view. The music of Martin is

known for sincerity, earnest qualities and sobriety; not for brilliance

or ecstatic statement. The closest British parallel might be Rubbra.

While Rubbra was a symphonist with eleven in his catalogue Martin had

only one. Rubbra was Roman Catholic and Martin Protestant. However their

music tends towards dour and dedicated. The uninitiated might brush

it aside as dull. Neither Martin nor Rubbra wrote a great deal of music

for solo piano but in this field the comparisons strain. Rubbra's piano

music is of lowish profile - devotional rather than brilliant. Martin's

piano music is wide-ranging in character. There are certain catalogue

similarities however. Rubbra wrote a Sinfonia Concertante for

piano and orchestra (with a middle movement dedicated to Holst in his

death-year) as well as a single Piano Concerto (discounting a very early

concerto). Martin wrote a Ballade for piano and orchestra and

two piano concertos.

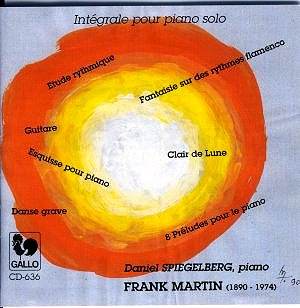

Spiegelberg is not a familiar name but his range and

imagination seem well matched to Martin.

The Danse Grave is an early work which derives

its character from the 'dompes' of Dowland and weaves this line with

the Pavanes of Fauré and Ravel.

Guitare is a four movement suite written originally

for Segovia but then transcribed by the composer for orchestra and for

solo piano. Not at all surprisingly the music carries the stamp of the

guitar. The first movement's ombrageous hispanicisms contrast with dazzling

brightness. The Air recalls Danse Grave. The strumming

of the Plainte is a direct tell-tale of the work's instrumental

origins. The Gigue is gawkily insistent. The suite would go well

with Lionel Sainsbury's Spanish pieces.

The quadripartite Flamenco Fantasy ends the

disc and it too looks to Iberian origins. While Martin's son provoked

in his father a delight in the bass tones of the electric guitar (surfacing

in one of his last works) his daughter’s love of flamenco gave birth

to a winter year’s immersion in recordings and concerts. The Fantasy

was the result. The rhythms clash and struggle in this work with a complexity

that others, pre-eminently Nancarrow, have solved with resort to the

player-piano. Martin liked a challenge and passes his victory on to

the pianist. The last two of the four sections are termed Soleares

and Petenra and here the crabbed tension of the early stages

of the dance are dissected in ominous steady grumbling and grunting

impacts - quiet and loud.

The Eight Preludes are caring and grave. They

in part pair neatly with Rubbra's piano music and with Rawsthorne's

Bagatelles. This is Chopin refracted, pensive and jangling (allegretto

tranquillo), dancingly like Rachmaninov in the fourth Prelude, in

another deploying constant pearling runs of notes vivace; at one time

satisfied with the stillness of Debussy crossed with Schoenberg (rather

like the isolated Clair de Lune piece) and finally jazzy, clear-headed

and gawkily angular. A steady all-elbows awkwardness extends to the

Etude Rhythmique and the Esquisse.

I started by making comparisons with Rubbra. We should

also look at another Swiss composer who is something of a Gallo speciality.

Richard Flury was born six years later than Martin and died seven years

earlier. Flury was an ultra-conservative musically coloured by his masters

Hans Huber and Joseph Marx. Martin took a quite different route - prizing

his own rather matte expressive language, much taken with Bach and choral

music. His music still struggles for recognition with an armoury that

lacks the qualities that instantly beguile. From the perspective of

the twenty-first century Martin, blessed with a name that sounds too

English and ordinary to be intriguing, is known by comparatively few

yet is well respected and even loved by connoisseurs. His music carries

the fibre and sincerity that will make it a natural target for the sort

of revival that Bach had from Mendelssohn. Flury has the sincerity and

as the generations roll forward the wholesale use of nineteenth century

German romanticism will matter less and less. However I doubt, on the

evidence of the two Gallo discs I have heard, that Flury has the intrinsic

memorability and sense of the special that will make his music stand

prominent in 2200.

Rob Barnett