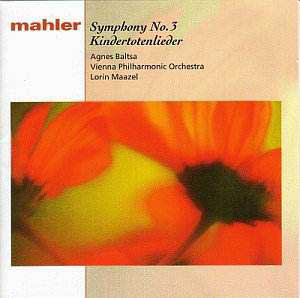

Maazel’s 1980s Mahler cycle was something of a curate’s egg.

At least one performance, the Fourth, received much praise and is still

a leading contender in various guides. Elsewhere, the main criticism tended

to revolve around rather slack tempos, flabby phrasing and a tendency

to over-indulge and luxuriate at the expense of the musical line. The

playing of the Vienna Philharmonic will always be praised, of course,

but on the one performance from this cycle that I owned, the Ninth, there

was a feeling that they were on overdrive. In fact, I only bought that

version because, if memory serves, it was the first digital Ninth to be

issued on CD. I soon dispensed with it when the real competition started

to be issued – Bernstein (particularly his Berlin version), Barbirolli,

Walter (Vienna), Karajan (the live second) and Rattle. Listening to the

re-issue of Maazel’s Third has re-kindled all those old feelings, though

admittedly it is now at bargain price, and has a fill-up that should be

taken seriously.

In the massive, sprawling first movement, "… the

most original and flabbergasting thing that Mahler ever conceived",

to quote Deryck Cooke, summer does not quite march in as one would like.

The big opening tune, announced on eight unison horns, and sounding

almost like a grotesque parody of the C major melody from the finale

of Brahms’ First, lacks the ‘vigorous, decisive’ manner that Mahler

asks for. It doesn’t help that the recorded sound is a bit recessed

and distant, lacking the sort of presence and impact given to others

(notably Abbado’s first version on DG). The sheer length of the movement,

and the amount of wildly contrasting material in it, demand a tight

grip, and Maazel’s rather tentative, almost ‘softly-softly’ approach,

does it, and us, no favours. The way that the various march elements

are developed needs careful consideration, and a strong characterisation

from the players. But the conductor must keep the tempo currents strong

and flowing. Maazel seems too content to let the music unfold episodically,

and even the massive exposition climax (between Fig.28-29) does not

sound enough like a culmination, but almost appears out of the blue.

To be sure, there is some fine playing, and the famous trombone solo

is nicely dispatched. But is this enough in this music? Do we really

feel the sense of the ‘primordial’ that Cooke talks about? I’m afraid

it all sounds a bit too safe and under-whelming for my liking.

The four shorter inner movements fare a little better,

though even here one senses little of the innocence and wonder that

other conductors are able to convey. The little A major ‘flower’ minuet

lacks the grazioso element Mahler asks for, though there is some

suitably fine wind playing throughout. The C minor ‘birds and beasts’

movement should surely have a livelier scherzo feel, and though other

conductors do take Mahler’s comodo marking as literally as Maazel,

they do manage to invigorate their players into giving sharper dynamic

contrast and greater characterisation. The post-horn solo lacks the

shimmering mystery that one gets elsewhere, and the great E flat minor

outburst towards the end of the movement (Fig.31) reveals some rather

sour tuning in the horns.

Maazel is probably at his best in the fourth movement,

helped immeasurably by Agnes Baltsa. This predecessor of the great ‘Abschied’

from Das Lied von der Erde is generally successful, with conductor

and soloist creating an atmospheric misterioso that works well.

In the ‘Angels’ fifth movement, the boys obviously enjoy their ‘bimm-bamms’,

and it’s difficult to ruin this entirely. But even here, I feel more

contrast could be made of the troubled middle section (say between Fig.

6-7), where Abbado, for one, digs deeper into the sub-text of the music.

From all I have said, one might imagine that the great

hymn-like Adagio finale would suit Maazel’s approach to perfection.

However, an extremely slow tempo is only one ingredient in the whole

picture. Many individual lines are beautifully phrased, but the counterpoint

must flow, and momentum be sustained, if the music is not to get bogged

down under its own weight. Bruno Walter showed many times that Mahler’s

slow movements could move on without the spiritual dimension being harmed.

By the same token, Bernstein and Haitink have shown us that the slowest

tempi can still have an intensity and controlled grip in the right hands.

In this recording, we do not experience, as fully as we might, an apotheosis

that transports us to a world where ‘Nature in its totality rings and

resounds’.

The Kindertotenlieder make a generous and welcome

filler. All are performed with great expression and intensity, and are

generally much more enjoyable than the symphony. Not all competitors

(particularly Haitink and Abbado) offer any extra music. Bernstein’s

mid-price Sony set offers plenty of extras, with Jennie Tourel singing

Kindertotenlieder and a selection from Des Knaben Wunderhorn.

Tilson-Thomas’s highly praised mid-price digital Sony set (with the

LSO) has Janet Baker in the great Rückert Lieder.

Given my reservations, and a rather backwardly balanced

recording, I find it hard to give more than a very qualified recommendation

here. Yes, it is cheap, but a few extra pounds will go a long way with

Mahler recordings these days. If money really is an issue, go for Tilson-Thomas

or Bernstein. A few more pounds will get you the inimitable Horenstein,

whilst at full price, Haitink, Rattle or Abbado (either recording) will

ultimately offer greater listening rewards.

Tony Haywood