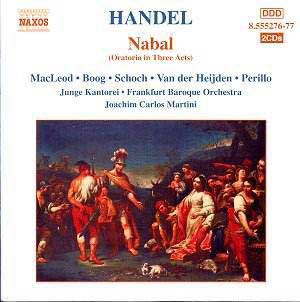

You doubtless wonít be alone in not having heard of

Nabal, a three act Handelian oratorio first performed five years

after the composerís death. It is not an original work by him at all

but rather one of the many examples of pasticcio, in which a

composite work is constructed through the use of excerpts from other

works or indeed other composersí works. In Nabalís case the conduit

was the eminently practical John Christopher Smith, son of Handelís

principal copyist, who had, when a boy of twelve, taken harpsichord

lessons from Handel. In 1750 Smith helped the ailing composer with performances

of his oratorios and was himself a valued musician, being organist and

choirmaster at the Foundling Hospital. After Handelís death he led an

annual performance of Messiah in his memory and subsequently

went on to work with Garrick, collaborating on three operas together.

The pasticcio suited eighteenth century entrepreneurial

spirit very nicely; it satisfied the continued thirst for oratorio rendered

problematic by the unavoidable absence of the formís principal producer

in London. Handelís death certainly didnít spell the end of Handelian

oratorio. The enterprising Smith, after a period of retrenchment and

manuscript searching, joined up with Thomas Morell to create new works

Ė Rebecca and Nabal were the first fruits of their collaboration

and both had their premieres on 16th March 1764. Nabal received

a further performance five days later but itís likely that it has never

been heard since, at least not publicly. Morell had written the libretti

for some of Handelís greatest works Ė Judas Maccabaeus, Theodora,

Jeptha and others Ė and he wrote a text drawn from Samuel 1:25,

one that fitted pre-existing music from a wide variety of source material:

operas, oratorios, anthems and cantatas. The recitatives are probably

the work of Smith himself. The booklet covers very well the attribution

of source material noting, where known, the original work from which

Smith derived the music and upon which Morellís new text was grafted.

In this kind of work one is constantly dimly aware of a half recognised

melody - and in the light of Handelís own borrowings and self-borrowings

the sense of absorption, digestion and renewal takes on a new form.

The performance is neat and conscientious, sometimes

more. Tenor Knut Schochís English is strongly accented and he has a

rather hollow quality to his tone and nothing glamorous about it. He

makes a real meal of the runs in the Third Part air Lovely beauty,

and struggles with the top of his voice here and elsewhere. But

he is an intelligent and understanding musician. Francine van der Heijden

has a sure instinct for Handelian line, great clarity and security of

register Ė I particularly admired her negotiation of the air The

lord, our guide derived from Muzio Scevola; a fine and valuable

voice for the Baroque literature. As for Nabal himself Stephan MacLeod

has a notably well modulated bass though one that can tend to bark

in the higher register Ė as he does in Still fill the bowl. Linda

Perillo, as the shepherd, is a playful and dramatically inclined soprano

but her production is uneven and can tend toward the erratic; in her

aria Gay and light as yonder sheep she negotiates her divisions

reasonably well but at 1í22 engages in some not especially attractive

gurgling. By contrast she is much more effective and successful, dramatically

and musically, when floating her voice. She is a most interesting singer

and itís to be hoped that something can be done to sort out her register

breaks. The choir sounds rather distant and diffuse; occasionally individual

voices can be heard, strands not ideally blended. The small orchestra

meanwhile is spirited and alert - nice string articulation in the instrumental

gavotte of the First Part Ė and take sensible tempi directed by Joachim

Carlos Martini though to my ears the chorus By slow degrees the wrath

of God is not well sustained at this slow tempo. Nevertheless this

is an honourable presentation of a work, the problematical and artificial

nature of which means that recordings will be few and far between.

Jonathan Woolf