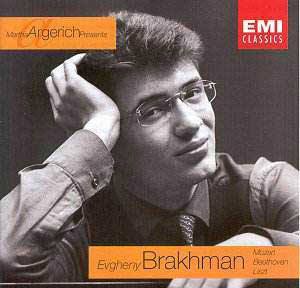

As is the way with modern marketing, Argerich’s name

appears as boldly as Brakhman’s on this debut disc from yet another stunning

young Russian virtuoso. Fair enough; the record companies have to try

somehow to attract our attention to what is, after all, a recital of very

well trodden territory. In fact what strikes me, on initial acquaintance

with this artist, is playing of exceptional clarity and lucidity, light

years away from Argerich’s volatile impetuosity, perhaps more akin to

a young Perahia. In one so young (20 when this was recorded) this is admirable,

though it does have its drawbacks in music as emotionally wide-ranging

as some of the works here.

Brakhman’s slightly cool, detached but very musical

style of phrasing is probably best suited to the Mozart. This marvellous

sonata, published in 1784, is the most extrovert of a set of three,

and displays a brilliance and energy that would fully show off the young

Mozart’s keyboard skills. So it does with Brakhman, and the crystalline

clarity of his scales and ornaments are something to marvel at. The

finale’s triplet figurations and Alberti bass really are superbly steady

– any budding pianist will know just how deceptively difficult these

common classical devices really are.

Beethoven’s spuriously titled ‘Tempest’ sonata

is less completely successful. I like his pacing of the difficult first

movement, and his very precise placing of the syncopated sforzando

accents. The finale is also brought off well, with the tricky broken

chords at 2.43 well handled. The problem lies in the great slow movement,

which is a shade under-characterised. The drum-roll-like accompaniment,

for instance at 5.50, simply lacks mystery, and turning to some of the

competition is not particularly kind to Brakhman. Richard Goode, on

a highly recommendable Nonesuch cycle, manages to convey greater depth

and emotion in this profound music. Similarly, Solomon’s classic reading

on EMI is a model of spiritual insight. Still, there is much to enjoy

in the sheer unaffected nature of Brakhman’s performance, and at least

he does not impose his own ego on the music.

Liszt’s monumental one-movement B minor Sonata,

however, does need something of an ego to make it fully convincing.

What we get, once again, are the notes, pure and simple, and in the

many long, intensely personal passages in this piece, that is not enough.

The opening, once again, lacks any of the anticipation of a great journey

about to be undertaken. The technique is certainly secure, and the fabulous

double octaves towards the end are breathtaking in their precision and

bravura. But this is a forward-looking masterpiece, and the structure

and contrast need to be clearly defined. Of the many versions in my

collection, the current favourites are Zimerman (on DG), Argerich herself

(also on DG, at mid-price), and, best of all, Richter, on stunning form

and superbly coupled with the two concertos (mid-price Philips). It

may sound like a cliché, but I’m sure the wisdom of age and experience

do bring benefits in music such as this. Richter’s technique may be

fallible in places (it is live, and sounds un-edited), but such is his

grip on the extremes of contrast and mood changes within the chameleon-like

structure, that the listener simply has to submit and be a participant

until the very last note sounds, and the great circle is closed. This

is surely the mark of a great performance, though Brakhman’s musical

intelligence and technique are such that he will almost certainly reach

that standard one day.

So, all in all, much to admire, if ultimately falling

short of the very best, especially given the incredibly severe competition

in the Liszt and Beethoven. The recording is good, though so closely

balanced that the piano’s damper mechanism is clearly audible through

most of the recital.

Tony Haywood