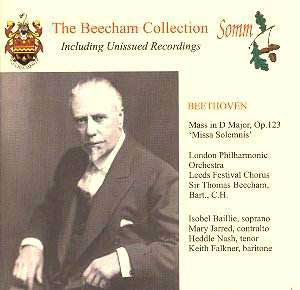

Simply magnificent. I am sorely tempted to leave it

at that because no words of mine could ever convey the drama, the majesty,

the intimacy and unexpected depth of this live performance from the

1937 Leeds Triennial Music Festival, one of only two performances of

the Missa Solemnis that Beecham ever gave. I say unexpected because

of Beecham’s occasional penchant for Beethoven-bating but this is a

searing and extraordinary interpretation by which I was completely transfixed

throughout its entire length. The performance was given on the morning

of the 5th October and repeated in London a week later at

a Royal Philharmonic Society concert. The only change was that for the

London performance Harold Williams replaced Keith Falkner. Of course

it’s not necessarily for the most fastidious of ears – there are some

minor aural problems; considerable timpani overload in the Kyrie

and some negligible wear on the unique copies that have survived in

otherwise impressive condition. One is acutely aware of the care taken,

despite Beecham’s operatic reputation in this regard, to balance choir

and orchestra and properly to integrate the quartet of singers. As a

result the solo entries emerge, in the circumstances, with remarkable

fidelity. In the Gloria Isobel Baillie’s soaring beauty of tone

and Heddle Nash’s ardent tenor entwine with a naturalness only enhanced

by Falkner’s own noble entry. When Mary Jarred joins, lending her consummate

contralto, the quartet and the timbres and intensities of its singers

become apparent – Baillie, crystalline and pure, Nash, with his uniquely

expressive lyricism, Jarred’s affecting plangency and Falkner’s deeply

considered seriousness.

The Choir’s dynamic levels have clearly been well prepared

and for that, I suspect, considerable praise was due to Norman Strafford,

the Leeds Festival Choir’s Chorus Master. The choral singing is deeply

impressive – the equal or superior of any choir in the land at the time

– and with one or two slight hesitancies apart, unstinting in its overwhelming

contribution. The grandeur and sweep of the Gloria is momentous

but precise. The male choral entries are as dramatically strong – but

scaled – as the female; whereas in the Et Incarnatus est from

the Credo there is a corresponding raptness, an inwardness of

expression, which reveals itself most fully in the unravelling of solo

voices. There is no false piety here – Nash’s clarion declaration swells

and falls, hardens and darkens and leads to the benediction of Jarred’s

consoling contralto; listen to the strings here at 3’26 for their acute

support and maintenance of line. Et resurrexit opens with implacable

choral power and the LPO are here on superb form, supportive of the

decisiveness and concentratedness of Beecham’s conception. The Sanctus’s

affecting tread is followed by a long solo for leader David McCallum

in the Benedictus – his sweet, concentrated tone is entirely

apt for the vocal quartet’s extraordinary intimacies of expression –

the way Baillie succeeds McCallum at 2’35 is truly astonishing, as she

coils her tone to blend and fuse with his. Felicities of this kind abound

and continue in the Agnus Dei; Falkner may not be ideally secure

here initially but he grows in control, freely rolling his "r"

with the passion of a Prophet and spreading his solid baritone ever

outward. Mary Jarred is especially fine here in her passages before

and with Nash and one can see why she was so admired in her day and

deplore that she is so unjustly forgotten in our own. The concluding

Dona nobis pacem has been hard won, through strife and loss,

but the abruptness of its final triumphant orchestral close seems to

catch the Leeds audience by surprise.

This performance has been issued before, on Beecham

5, where it was coupled with a performance of Beethoven’s Second Symphony

from 1936, to join the three commercially recorded versions of the Symphony.

As for the Missa Solemnis it is now the earliest surviving performance

on record and one of the most incandescent and moving.

Jonathan Woolf