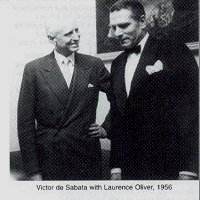

I purposely included the picture of Laurence Olivier with Victor de

Sabata, in this review, so that I could provoke immediate, subliminal

theatrical and cinematic associations. This highly colourful, dramatic,

generously melodic music could so well have been written for the screen.

So often it reminds one of the heady effulgence of Max Steiner and Korngold

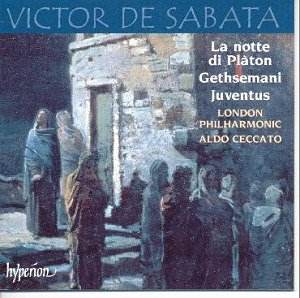

in full flow. Hyperion is therefore to be congratulated on recording

these terrific works; it is only to be regretted that de Sabata wrote

so little. It all comes as something of a surprise when one remembers

De Sabata as a gifted conductor. In that capacity, he has left a significant

legacy of recordings of late Romantic and Impressionist music, notably

recordings of works by Debussy and Respighi; and probably the best-ever

recording of Puccini’s Tosca with Callas, di Stefano and Gobbi

(reissued this month by EMI, at mid-price in their ‘Great Recordings

of the Century’ series). [Considering that opera was really the only

genre in demand in Italy, and that so few Italian composers broke away

to compose orchestral or other forms of music (Respighi for instance)

might explain why de Sabata was discouraged from further composition.]

La notte di Plàton (The Night of Plato), written

in 1923, represents the opposites of hedonistic pleasures of the flesh

and the quiet restraint and introspection of the spirit. De Sabata choses,

as his illustration, Plato’s last feast before renouncing pleasure to

follow the teachings of Socrates. A sumptuous, grandiose work, scored

for a huge orchestra, it is extremely colourful and exciting in its

wild orgiastic dances and languid and voluptuous in its suggestion of

carnal earthly pleasures. All this abandon is contrasted with calmer

contemplative material and a memorable melody, aspiring and noble. The

influences are numerous: Richard Strauss certainly, probably Respighi,

and perhaps Mahler.

Night descends on Gethsemane. Peace and tranquility reigns. Pilgrims

looking towards the heavenly stars are overcome with holy ecstasy in

contemplation of the Saviour’s suffering and God’s promise… This is

the scenario of De Sabata’s 1925 composition, Gethsemani

(poema contemplativo). The entire thematic material is based on Gregorian

chant subtly stated at the outset and developed with great beauty and

refinement. This is descriptive, impressionistic music, predominantly

serene and contemplative, the music fragrant colourful and evocative

of moonlit fountains, flowers and birdsong. The violence of our Lord’s

arrest is beheld at arm’s length and not allowed to intrude into the

foreground. The momentous, yet slowly gathering Romantic climax is more

in keeping with the Passion of Christ’s love for the world and its redemption,

rather than his suffering (although, in the decrescendo, this image

may be just apparent). One can easily imagine this music being used

in some Hollywood biblical epic.

Probably the most ‘Golden Age of Hollywood’ - like music comes in

the shortest of the three works, Juventus (Youth), composed

by De Sabata in 1919. In this composition, De Sabata sets confident

thrusting music against passages of restraint to suggest the joy and

passion of youth as opposed to the hesitant, inhibition and disillusionment

of increasing years. In this fulsome melodic composition, in De Sabata’s

most Romantic voice there are pre-echoes of Max Steiner and Korngold.

I feel sure, for instance, that Bette Davis would have given her eye-tooth

to have this composition underscore Dark Victory or Mr Skeffington.

For all unashamed romantics -- this recording is absolutely fabulous.

Don’t miss it. If only today’s composer’s of film music could find such

a lyrical and unrestrained voice. I hope that Hyperion can find enough

material to produce a second ‘composed by Victor de Sabata’ album.

Ian Lace