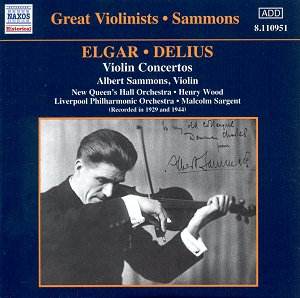

Naxosís series of historical issues has already brought

forth a stream of important releases but this, I venture to suggest,

may be the most significant to date for it couples and potentially puts

into a wider circulation than ever before two recordings of supreme

importance in the recorded history of English music.

Albert Sammons (1886-1957) was arguably the greatest

virtuoso violinist this country has ever produced. His recording of

the Elgar concerto was the first uncut one to appear and Delius was

inspired to write his own concerto (for Sammons) after hearing him play

the Elgar in concert. Sammons gave the first performance of the Delius

concerto and was the obvious choice to make its premiere recording,

here reissued.

The recording of the Elgar was made in 1929, three

years before the composer made his celebrated recording with the sixteen-year-old

Yehudi Menuhin. Sammons had already made an acoustic recording of the

work in 1916, also with Sir Henry Wood conducting, but that performance

suffered from cuts. As Tully Potter points out in his notes, the Menuhin

account has always overshadowed that by Sammons and it has been consistently

available whereas the Sammons recording has been in and out of the catalogue.

I think Potter is absolutely right to praise Sammonsí recording but

I do rather part company with him when he dismisses the Menuhin performance

as one which is "nicely played, to be sure, but sounding more like

the work of a sixteen-year-old with each of its manifold reissues."

In my opinion, no allowances need be made for Menuhinís age. His is

a performance which thoroughly justifies its classic status. Sammonsí

performance too is a great one but it needs no denigration of a rival

to advance its cause.

I think the crucial difference is that Menuhinís account

of the solo part, while characterful and entirely assured, is a part

of the overall performance whereas Sammons dominates his recording.

This is apparent from the very first entry of each soloist. Both command

attention but Sammons, with his huge tone, is the more rhetorical, more

questing. In part Iím sure that this is a question of mental and physical

maturity. Menuhin, after all, was only sixteen years old at the time

of his recording while Sammons was forty-three with a much longer career

behind him. Menuhinís is the voice of youth, Sammons represents experience.

However, I think that the role of the respective conductors

must not be overlooked. They are as different as chalk from cheese.

In the first movement in particular Wood presses ahead vigorously whereas

Elgar is more ready to linger. Anyone who has performed Elgarís music

will know that often it seems that there are scarcely two consecutive

bars without a tempo modification, however subtle (all precisely noted

in the score). I welcome Woodís urgent basic tempo for the first movement

in particular but to my ears at least there are times, particularly

in that first movement, when he seems reluctant to relax when the music

demands it. Tully Potter perceptively comments that Elgar might have

been too self indulgent a conductor for Sammons and that Wood was a

better foil for him. Iím sure this is right but I would still have loved

to hear Sammons and Elgar in partnership. As it is, Wood takes two and

a half minutes less than Elgar for the first movement, and lops some

two minutes off the composerís timing for each of the other two movements.

Mere timings donít tell the full story, of course, but Iím sure it's

not just greater familiarity with the Elgar recording which makes me

feel more at ease with the pulse which the composer sets in each movement.

To return to the soloists. Sammons dashes off every

one of the manifold technical difficulties in the first movement (as

he does throughout the work). I have referred to his big tone but his

dexterity in the many filigree passages is just as breathtaking. Mind

you, Menuhin is not found wanting technically either. His finer tone

has more of a will oí the wisp quality about it.

The contrast of tone is important also in the slow

movement. Menuhin weaves a seamless web with poise and delicacy. Sammons

is no less refined but his tone is more full-bodied and this allows

him to invest the music, and the closing bars in particular, with a

yearning nostalgia which is most moving. Comparing and contrasting the

two is rather like hearing the same music sung by a soprano and a mezzo-soprano:

both are beautiful but in a different way.

Both Sammons and, pace Mr. Potter, Menuhin give

deeply satisfying accounts of the difficult finale. For me, however,

the defining moments come in the accompanied cadenza which Naxos sensibly

presents on a separate track (as do EMI on my copy of the Menuhin, contained

in Volume 2 of their Elgar Edition). Here, excellent though Menuhin

is, Sammons takes us to a different level of musicianship. As so often

in this recording it seems to me that itís the actual tone which is

so crucial. One takes for granted technical prowess but whenever the

music becomes reflective and nostalgic Sammonsí burnished, nut-brown

tone, his greater maturity and his consummate understanding of the music

and the idiom adds an extra dimension.

As I have already indicated, my admiration for the

Sammons performance does not lead me to denigrate the Menuhin account.

That remains a very special experience with a precocious young soloist

inspired by and inspiring a conductor nearly sixty years his senior.

The Menuhin performance also benefits from the unique authority of Elgarís

presence on the rostrum (he was an excellent conductor of his own music)

and from better sound which lets more orchestral detail register. However,

Sammons is, I think, hors concours. It is a compelling, magisterial

performance by a very great player. Iím just profoundly grateful that

we have the opportunity to compare and contrast two great performances

and to return with pleasure to either.

The Elgar is one of the greatest of all violin concertos.

The Delius concerto is not in that league but it is a lovely work. Sammons

makes a strong case for it. Indeed, he gives the solo part the kind

of strong profile which is so necessary if sections of the work are

not to appear to ramble a little. He projects the solo line very characterfully

and though he makes a generous sound he proves capable of spinning a

subtle, rhapsodic line above the stave. He is ably supported by the

Liverpool orchestra under Sargent. This was but one of several fine

recordings which this orchestra made for Columbia and HMV around this

time (one thinks of the premiere recordings of Holstís Hymn of Jesus,

Elgarís Dream of Gerontius, both under Sargent, and Waltonís

own recording of Belshazzarís Feast.) Sargent was clearly no

mean orchestral trainer as these various recordings show. Furthermore,

in this Delius piece his accompaniment seems to me to be just as idiomatic

and characterful as is that which Beecham, no less, provided for Jean

Pougnetís 1946 recording.

Mark Obert-Thorn has produced very good transfers of

both recordings. So far as I know this is the first time that these

two performances have been coupled on CD. They are magnificent accounts

of two very different works and the appearance of this Naxos release

is a cause for rejoicing. Sammonsí account of the Elgar concerto, in

particular is mandatory listening for all lovers of English music. This

is an essential purchase and at the Naxos price represents absurdly

good value for money.

Recommended with all possible enthusiasm.

John Quinn

And Rob Barnett writes:-

And still they come in Naxos's rapid and smilingly

relentless flow of historical reissues.

This disc acts as a companion to the three volume Beecham

Delius series and as a complement to the Walton/Elgar violin concertos

Heifetz CD.

The coupling is astute ... even politic. Both recordings

are well known and are currently available in the case of the Elgar

on Pearl and for the Delius on Testament. The Pearl (GEMM CD9496)

is coupled with Sammons in the Elgar Violin Sonata with William Murdoch.

The Testament (SBT1014) is a long-established Delius concertos disc

with the Piano Concerto (Moiseiwitsch) and a sprinkling of Delian brevities.

Sammons is very smooth of tone, sweet-toned and ever

so slightly acid - like the song of a blackbird. This is the first ever

recording of the Delius concerto by the soloist who premiered the work.

He gives a great feeling of continuous song without angular edges but

with plenty of variety and accenting along the way. Ida Haendel's Proms

broadcast with the BBCSO and Rozhdestvensky in the 1980s was even better

but this is no longer available (it used to be on the BBC series from

IMP).

The Elgar recording does not sound fourteen years older

than the Delius. The orchestral role is distanced by the exigencies

of 1920s recording technology but the violin squats centre-stage in

secure focus and the range from pp to ff is represented

with fidelity. The interpretation does not dawdle but neither is it

insensitive. Sammons is good at the drama, impetuous, plays up a storm

and conveys surging energy rushing forward yet never scouting detail.

If you don't know the recording sample the last five minutes of the

first movement.

Choose your coupling and your price and take your choice.

The Naxos is an inexpensive choice but it depends ultimately on what

you want. If you need a complete Delius or Elgar disc then go for the

Testament or Pearl. Otherwise the Naxos will give you two classic recordings

of two great concertos (nationality issues are irrelevant) in the hands

of a modest and sincere musician who never attained nor even wanted

international stardom.

The age and analogue origins of the recordings are

declared by the ultimately reticent bed of 'shush'. This is only a shade

more 'brambly' in the Elgar. Side change transitions are imperceptible.

The liner notes are by Tully Potter and are well up

to his usual exalted standard. He says about the famous Menuhin recording

that overshadowed the Sammons exactly what I have thought for years.

Place this version of the Elgar on the shelving next

to the Heifetz, Accardo, Hugh Bean (at least if you have been able to

prepare a CDR of his 1970s Classics for Pleasure LP pending its too

long deferred appearance on commercial CD) and the Zukerman.

An inexpensive way to add to your collection two well-loved

archive recordings of the Elgar and Delius. The Elgar, in particular,

still has the power to startle, stir and delight.

Rob Barnett