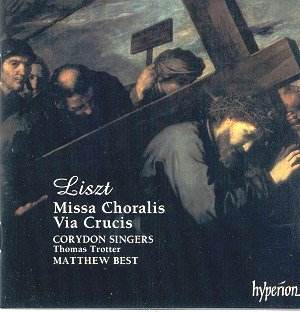

FRANZ LISZT

Missa Choralis

Via Crucis

Elizabeth Atherton

Soprano

Elizabeth Atherton

Soprano

Jane Bovell Soprano

Harriet Webb Mezzo-soprano

Jeanette Agar Contralto

John Bowley Tenor

Peter King Tenor

Leigh Melrose Baritone

Nicholas Warden Bass

CORYDON SINGERS

Thomas Trotter Organ

Matthew Best Conductor

Hyperion CDA 67199

Hyperion CDA 67199

Crotchet

£11.99

Amazon

UK £11.99

AmazonUS $17.97

Liszt's Missa Choralis was written in 1865 during the period he was

resident in Rome and took holy orders. He spent much of this time following

an almost monastic existence as guest of Cardinal Gustav Hohenlobe, and devoted

himself to studying and composing church music - including the oratorios

St Elizabeth and Christus. All of this was in stark contrast

to his life in the 1830s and 1840s when he was constantly touring all parts

of eastern and western Europe, enjoying a flamboyant, raffish, womanising

lifestyle and revelling in the adulation of his besotted admirers. His apparently

abrupt transition from the profane to the sacred puzzled many at the time

and ever since. We should recall however that, after high public exposure

as a child prodigy, he spent his adolescent years, following the death of

his father in 1826, in much religious reflection and reading. It was

only in his 20s and 30s that he became fired up and embarked on the "outrageous"

compositions and performances for which he is best remembered. We may conclude

that Liszt's period as Kapellmeister at Weimar (1848-58) saw a re-awakening

of his youthful religious preoccupations. Certainly his move to Rome occurred

with a sense of mission: to restore mystical depths to church music and rescue

it from the "operetta" style into which it seemed to have degenerated - hence

his deep study of Palestrina. Set in this context, we can understand the

pivotal importance of the Missa Choralis in Liszt's musical and

psychological development.

Whatever his admiration for Palestrina, and his occasional incorporation

of plainchant themes and use of mediaeval modal tonality, Liszt's music here

is in no way derivative and contains no complex polyphony. Much of it is

either unison or homophonic. It is essentially the simple expression

of profound emotion, yet expressed in terms of wide ranging changes of tonality

- sometimes abrupt and sometimes so skilfully subtle that the listener is

unaware of just how bizarre a journey of modulation his ears are being taken

through. The structure of the movements follows 18th century

convention, in its reflecting the mood and sense of the text, and in the

alternation of soloist ensemble and full chorus. The setting could thus be

said to stand in line of descent from the tradition of Haydn and Mozart -

but, importantly, with the "operatic" frills removed: there are no ornate

melismata and no long instrumental ritornelli. The organ accompaniment, where

used, is complementary and almost never heard on its own. The singing is

thus a capella with organ support. The music is amply served by the

Corydon Singers under Matthew Best. This choir has a well-earned reputation

for 19th and early 20th century choral music and its

talents are ideally suited to this rendering of Liszt. Especially profound

poignancy is achieved in the angst sections: Qui tollis in the

Gloria and Crucifixus in the Credo.

Via Crucis also comes from Liszt's "religious" period, being composed

in 1866. It illuminatingly shows how the mind of the creator of this music

was all part of the same joined-up psyche as that of the composer of his

most extravagant piano and orchestral works. It belongs to that favourite

formula of Liszt: a sequence of short movements based on pictures or statues

- in this case the Stations of the Cross - each one a miniature cameo of

penetrating intensity. A range of texts and themes are used to illustrate

the Station's devotions: Latin hymns (including lines from Vexilla

regis, Stabat mater and Ave crux), Lutheran chorales (his

own harmonisations - not the familiar ones of Bach), quotations from the

Bible, and organ solos. With fifteen movements, lasting very few minutes

each, the whole work's integrated consistency is achieved by much thematic

and textual cross-referencing (as matches the narrative sequence) and by

the repeated use of "The Cross" leitmotif - a rising sequence of just

four notes - two tones and a minor third. These also form the very last notes,

played pianissimo on the organ, of the whole work.

The Corydon Singers and soloists extract the poignant and mournful depths

of the music in full measure. There is no catharsis here, no sneakily

anticipating the resurrection; it is profound pathos and anguish throughout.

It is not for everyday listening - or indeed for recreational concert hall

performance at all. Perhaps this disc should come with a warning label directed

at potential listeners with depressive or suicidal tendencies? Certainly

intense concentrated listening does induce morbid introspection of the darker

regions of the soul. On the other hand, if given less close attention, the

listener risks becoming merely bored. This may go some way to explain why

the work was rejected for publication at the time of its composition and

was never heard in Liszt's lifetime - or indeed until 1926.

This disc will not be everybody's cup of tea. However the quality and

authenticity of the performance makes it especially valuable for those who

wish to enrich their understanding of this key phase in the evolution of

19th century choral music. These are certainly works of a rare

genius, combining (as they do) without inconsistency the ancient traditions

of plainchant with the mould-breaking iconoclasm of mid-19th century

romanticism.

Humphrey Smith