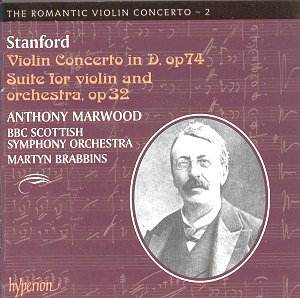

Charles Villiers STANFORD

Suite in D, op.32 for violin and orchestra;

Violin Concerto no.1 in D, op.74

Anthony Marwood (violin)

Anthony Marwood (violin)

BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra/Martyn Brabbins

Hyperion CDA67208

[66:40]

Hyperion CDA67208

[66:40]

Crotchet

AmazonUK

AmazonUS

Stanford's writing for violin and orchestra was fairly extensive. An early

concerto (1875 - the same year as the first symphony) was suppressed but

not destroyed and was followed by the Suite on this record which Joachim

played at the famous Stanford concert with the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra

in 1889 (how many British composers since have been invited to conduct an

entire programme of their music with that orchestra?).

The first concerto likewise enjoyed distinguished advocacy from its dedicatee

Arbós and from Fritz Kreisler, no less, yet it may not have been played

between 1918 and this recording of 2000. Maybe it was the chance to rehear

this first concerto which inspired Stanford to write a Second in 1918, followed

by a set of Variations in 1921 and the Sixth Irish Rhapsody in 1922 (recorded

by Lydia Mordkovich on Chandos). The Second Concerto and Variations may have

survived only in MS transcriptions for violin and piano. Still, the full

score of the First Concerto is a recent discovery so let us hope this disc

will one day have a companion.

Stanford can be a puzzler, to those who know a wide range of his music even

more than to those who don't. The Suite is a far from lightweight piece composed

in a romantic idiom with sensitivity and obvious feeling, and with no apparent

resemblance to any other Stanford work I know. The sheer variety of his output

is such that we will never entirely know him until all his music is available

to us (and that would be a very large-scale undertaking indeed).

I think that, had I heard the Concerto "blind", I would have recognised the

composer from the cut of the themes, yet it expands our knowledge of him

wonderfully. The way in which the innocent opening is expanded to support

effortlessly the vast structure of the first movement is unprecedented in

my knowledge of his work. Nor does he flag in the slow movement, which expands

passionately in its central section and closes with deep poetry (and what

formal originality, again, to have the cadenza in the slow movement rather

than the first, as usual), or in the finale with its entrancing folkloristic

colouring.

A little bird (present at the sessions) had warned me that the performers

had taken the first movement too slowly. I disagree. I think they have understood

perfectly the still soul at the centre of the work, which the grander moments

rise out of but never dispel (even in the lively finale it is the poetry

which remains in the mind). Since I have sometimes been critical of Stanford

performances which others have lauded to the skies (the Varcoe song-recordings,

for instance) I hope my total praise for the performances on this disc will

ring all the truer.

I have always felt that Stanford was a great composer only in his smaller

vocal works, and perhaps the Irish Rhapsodies. Despite fine and magnificent

moments, even whole movements, in the not inconsiderable series of instrumental

works which we now have on CD, I can't quite place the piano concertos among

the great piano concertos or the symphonies among the great symphonies. I

hope I won't be repenting in ten years' time for my rashness but this violin

concerto really does seem to belong among the great violin concertos. How

interesting that he achieved this in a work which completely abandons Brahmsian

structural logic in favour of an anticipation of Sibelian "growth-and-collapse"

which allows him to unlock his true romantic nature.

Snap up this beautifully engineered disc without delay - I can't recommend

it too highly.

Christopher Howell