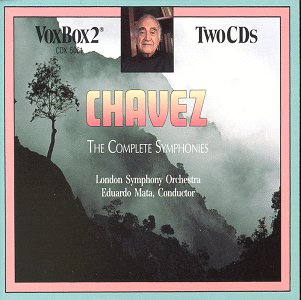

Carlos CHAVEZ (1899-1978)

The Complete Symphonies:-

Nos. 1 (Sinfonia de Antigona); 2 (Sinfonia India); 3; 4 (Sinfonia Romantica); 5; 6

London Symphony Orchestra/Eduardo Mata

rec. 1981

VOX BOX CDX 5061 (2 discs, DDD) [135.01] £9.99

Crotchet AmazonUK AmazonUS Amazon recommendations

I just love Vox Boxes! Perhaps I should quickly add that this is not a deeply considered critical opinion, but an emotional hangover from my youth - those (regrettably long-gone) halcyon days when absolutely everything was new, fizzy-fresh, and infinitely exciting. It all started when, as a junior school-boy, I would zip out of the local sweet-shop clutching in my grubby mitts a "lucky bag" that had cost me the princely sum of 3d. (yes, three denarii - proper pennies!). My pals and I would sit and rummage through our treasure troves, scoffing the sweets (though God knows what they contained) and noisily comparing notes on the tatty trinkets we found in the bags. We were probably being robbed blind, but that didn't matter in all the excitement and fun of discovery. In my early teens, a similar situation held as I clawed my way into Music, only now the "lucky bags" came in the form of cheap LPs (at 9/11d. a throw), the music was gobbled down with the same uncritical approval as those shoddy sweets, and also doubled as the discovered trinkets (indeed, most of it was inevitably unknown to me). Then a pal of mine got a summer job at the town library, and started bringing these sets of LPs from the record department. They usually contained rather more exotic fare, with composers of whose very names we'd never even heard - the archetypal "musical lucky bags": Vox Boxes. The difference was that these were not daylight robbery, and the contents were not usually likely to induce gippy tummies!

After CD booted LP into touch, we (members of the class of impecunious, or simply tight-fisted, record collectors) found ourselves forcibly removed from our utopian bargain-basement adventure playgrounds and deposited in a posh - and horribly expensive - department store. The affordable thrills of Vox Boxes and their ilk perished in parallel with the LP market. I can still remember my dismay, having only a year or two previously bought a DG Privilege double LP of Mravinsky's Tchaikovsky Symphonies Nos. 4-6 for under a mere two quid, at finding that the CD remastering would set me back over £28 - for a flamin' reissue, mind! Nearly twenty years on and the thing's still in the catalogue at full price - is this some sort of record?! Fortunately, the cold, dark night of deprivation was short, as first came Pickwick, then the meteoric rise of Naxos. The game was back on, and was eventually capped by the re-emergence of the good old Vox Box, managing to look on CD as reassuringly cheap-and-cheerful as ever it did on LP! Take a look at the cover on this one, so basic that it makes your mouth water in anticipation! Open the box - curiously enough, not a slim-line, but one of the old-style bulky ones (maybe Vox got hold of a huge job-lot?) - and take out the booklet. It's printed, in plain black-on-white, on paper that's only half a step up from newsprint (i.e. the ink stops short of actually blackening your fingers). Ah, but open it and you find, behind the front cover, fully seven pages of notes, and there's none of that infuriating multi-linguality - every word is in English! What's more, the essay itself, combining notes by Gloria Carmona and Julian Orbon, is sufficiently detailed and erudite to satisfy a fair range of punters. Maybe the focus on the formal aspects of the music is too much at the expense of the elaboration of the expressive, but that's a piddling quibble - these are, when all's said and done, supposed to be symphonies. There's more to "quality" than eye-catching colour print on glossy (and damnably dazzling) paper, and I reckon that on quality this booklet scores where it really matters.

I haven't mentioned the music yet, have I? Sorry, I got a bit carried away on a nostalgia trip. Right - Carlos Chavez. He's hardly been in consistent demand on "Housewife's Choice", has he? Yet RB in his review of Chavez' own recordings of the First, Second and Fourth Symphonies, observes that "These recordings are significant documents in 20th century music", and if you look him up you discover that Chavez himself is one of the most significant figures in Mexican music - not only as a composer, but also as a teacher, educational administrator, conductor, promoter, and publisher. He wrote a considerable amount of music, including lots of orchestral and solo piano music, ballet, band, an opera, incidental and chamber music, vocal and choral music, and (believe it or not) a Partita for Solo Tympanist ! Chavez was also instrumental in establishing a national identity for Mexican music, frequently drawing on the pre-Hispanic culture. In passing, I can't help but observe how we Europeans seem to have been in the habit of muscling into a country and annihilating the natives, then dutifully preserving and exalting their "lost" cultures. Ah, well, better late than never.

The booklet starts with an absorbing discussion of why the Symphony hasn't really ever been taken up by Spanish/Latin American composers, which boils down to their natural flair being for variational rather than motivic developmental forms. This of course provides us with an exceedingly subtle clue as to what makes these symphonies by Chavez, along with those of Villa-Lobos, so important. Apparently, his obsession with motives was such that his scores of Brahms' symphonies and the symphonies and quartets of Beethoven were peppered with annotations, encrusted in layers of ever greater detail until there was hardly a pair of notes that wasn't traced back to some earlier motive, and thence to one or another of the main themes. However, to be told that he was "into" motivic score analysis seems to me to beg the question: what we really want to know is what set him off along this congenitally contrary trail. Maybe he was "influenced"? Apparently not: he followed no-one, trusting instead in his own judgement and analysis, and of those composers he did particularly befriend - Dukas, Varese and Copland - only the last was anything like that way inclined. In any case, before he'd even had the chance to be "influenced" by anybody, as a mere slip of a 15 year old the largely self-taught Chavez was already writing a symphony (sadly, not numbered among those in the present "complete" set - now, that would have been a real treasure to find in this Vox "lucky bag"!), having only ever heard a symphony orchestra play just once in his life! Tracking back, I discovered that at just 12 he swallowed whole Albert Guiraud's "Traité d'Instrumentation et Orchestration". I've not read it myself (nor am I likely to!), but it might be a fair bet that the symphonic spark came courtesy of M. Guiraud's treatise, don't you reckon? If so, it's one of those happy accidents that occasionally enriches our world. On the other hand, it was to be fully 15 years, plus a bit of exposure to outside influences, before he rolled up his sleeves for his Symphony Number One proper.

Of these six symphonies, the only one that's even remotely well-known is the Second, the Sinfonia India. Like many other folk, I came across - and was bowled over by - this in Bernstein's electrifying performance on a CBS recording of the 1960s. If your only knowledge of Chavez is this luscious amalgam of pulsating rhythms and reworked Indian melodies, succulently scored for a ripe romantic orchestra positively bristling with exotic Central American percussion, you could be forgiven for concluding that Chavez had set off hot-foot along the path of Nationalism, as Dukas had encouraged him to do. That is my own conception, or it was until as recently as a couple of years ago when I heard an excellent Batiz recording including Symphonies 1 and 4 (ASV CD DCA 1058). In no uncertain terms, that kicked my conception into a cocked hat. With all six symphonies to go at, the shock value of the present set is even greater, throwing the Sinfonia India into sharp relief as a one-off. Although it is atypical of Chavez the symphonist, this is mainly down to cosmetics - behind its gaudy "nationalist front", the processes at work are every bit as symphonic as those of the other five.

The First Symphony, Sinfonia de Antigona, appeared in 1933, hot on the heels of, and apparently drawing on materials from, his incidental music for the Sophocles drama. Its generally slow-paced, polyphonic, classical austerity is leavened by occasional dance-like episodes, and throughout by colourful, imaginatively differentiated, almost pointillist orchestration (even experienced purely as sound, it's utterly riveting!). For orientation, you could, just about, pitch it between the Stravinsky of Orpheus and a Satie Gymnopédie, although with growing familiarity you soon become conscious of a warm heart beating within its cool flesh.

After the Second (1935), there was a gap of 16 years before the Third Symphony appeared (1951). During this period, his talents as an arts and education administrator cost him more and more time, leaving less and less for composition. Eventually, he even had to give up his position with the Orquesta Sinfonía de México. Perhaps, then, it's less than entirely inexplicable why his Third should set off with such towering anger! There is the same "warm-hearted austerity" of style that characterised the First, but the classical Greek coolness is here supplanted by much grittier sonorities. Gradually, through the inner movements, the clouds withdraw and let out the sun, and in the finale, emerging from gloom through ferocious agitation comes a hard-earned victory. In 1952, he rearranged his life to make more room for composing!

The last three symphonies, tumbling out in relatively short order over the next 8 years, were all commissioned by organisations in the USA (Louisville SO, Koussevitsky Foundation, and NY Lincoln Centre respectively). Perhaps that's why the Fourth contrives to work in a memorable melody in the "Mariachi" manner, as a sort of musical "greeting card". Heard in isolation, you might have trouble squaring the Romantica title with the form and content of the symphony, but in the context of the set "it ain't so hard". The style, as ever, retains the now-accustomed polyphonic severity, but elements of melting lyricism and more overt fervour (on top of that cheerful tune in the finale!) are now cracking the crust and bubbling through (dare I say, "like hot lava"?).

Symphony No. 5, by way of contrast, takes us right back to the Concerto Grosso style of J. S. Bach and company. I say the "style", because this is no piddling pastiche - the content remains thoroughly in character. By scoring it for strings alone, Chavez frees himself to concentrate more fully than usual on his beloved motivic processes, producing a stream of invention that will make the "pattern solvers" among you as happy as pigs in muck. I hasten to add that colour is by no means neglected: Chavez seems to be as alive to the potential of string sonorities as ever was Bartók. It's worth noting that, in the 1920s, Chavez was instrumental in promoting the music of such as Bartók, Les Six, Stravinsky, and even Schoenberg and Varèse in Mexico - he may not have "followed" anyone, but he sure as heck didn't ignore what was going on in the musical world around him!

In a way, the Sixth Symphony stands as a culmination to his life's work, even though he had a good number of productive years still to come. As the booklet says, the "urge to experiment is absent, unless the experiment here consists in accepting the challenge of the great classical forms in all their immutable majesty". I'd probably go along with that, apart from that "immutable" bit. Certainly, the symphony's opening, robust, open-air, and optimistic, has the quality of a composer at the height of his powers and at ease with himself. That it also has overtones of Copland about it is entirely apposite: Copland was after all his friend, and the work was written for his friend's home town. Mind you, there's also an elusive flavour that at first teased me rotten, until with a shout of triumph I caught on: Ives' Second Symphony of all things - I wonder if Chavez ever came across it? His main challenge was the finale, a massive passacaglia that he must have known would invite comparison with Brahms. Suffice it to say that Chavez, utterly unfazed at this prospect, stuck to his guns and produced an imposing edifice, growing out of the gruff tones of a solo tuba and culminating in a vast, cumulative fugue. Awesome!

Here I must issue a warning: if you're expecting from this set five more "takes" on the Sinfonia India, stay well clear! Chavez is, at heart, a very serious symphonist. It might have been Mahler who originated the wholesale use of polyphony in the symphony, but Chavez takes it even further, generally adopting a thorough-going, "severe" style very similar to that of J. S. Bach. Yet, like that great contrapuntal master, Chavez creates music that is at once "cerebral" in its complexity and exciting to listen to. If you enjoy unravelling contrapuntal knots, you'll be in your element. If not, you'll find the music simply knotty - but don't despair, because Chavez also has textural ingenuity in full measure: the sounds he can draw from an orchestra are stunning, and (again like Bach) the more you listen the more "heart" you discover. It can be tough to get "into", but once "in" you'll find it just as tough to get "outof"!

The performances are conducted by Eduardo Mata, who is now tragically lost to us. This recording stands as a fine testament to his talents. A Mexican himself, he did an enormous amount to further the cause of his own "local" music. If you ask me in what way Chavez sounds "Mexican", I would have to say, "Chavez sounds Mexican in the same way that Copland sounds North American". Mata, who was himself a composer, has the same blood running in his veins as does Chavez, and boy, does it show! The orchestra though, is British (although I can't vouch for the provenance of its individual members), yet to my ears they sound thoroughly idiomatic - no doubt Mata saw to that! Their playing is terrific, other than a very few places where I felt the odd twinge of strain but, as this probably reflects more on the demands made by Chavez than the capabilities of the players, I'm not about to quibble about it: the performances, which are well up to the standard displayed by that ASV disc I mentioned, "feel" right, and that's what matters.

Finally, coming full circle, one of the things about the old Vox Box LPs was that they often sounded like "stereophonic MW radio". No such worries here: the sound is perhaps a nadge on the dry side, with the ambience a bit recessed, but it is pretty full and warm right across the spectrum. The stereo spread is wide, with instruments in pin-sharp focus. I am especially pleased to report that the percussion are not "subtly" balanced - you can (as is often not the case these days) actually hear them! The over-riding impression is that the engineer (Bob Auger) was well aware of the composer's contrapuntal complexities, and did all the right things to maximise the all-important clarity of the sound-picture. Now, that's "cheap and cheerful" for you, and no mistake!

Paul Serotsky