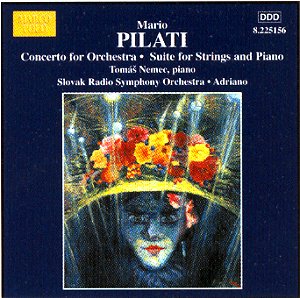

The curiously mono-nomenclatured conductor, Adriano,

also writes the extensive programme notes for this CD. This he does

passionately and with considerable persuasion, but he says (and this

is quite likely to put listeners off), Pilati’s output "over a period

of only eighteen years is already full of surprises and of great maturity,

leading the present writer not to hesitate in regarding him as a genius."

Mario Pilati was born in Naples in 1903 and is therefore

some 25 years younger than the Respighi and Casella generation and belongs

to a disparate group of composers which includes Petrassi, Dallapiccola,

Rieti and Nino Rota. In truth he does not fit into that group. His short,

and one must say unfulfilled, life never allowed him a chance fully

to develop, to have his music promoted or to be taken up by leading

figures. Much of it remains published. These factors never allowed the

composer to develop his burgeoning and promising voice.

There is enough on this CD to show that Pilati, who

was very prolific, was a promising and very fine composer. A great one

… ? Well, perhaps Marco Polo will allow us more opportunities in the

future to decide on that one.

There are certainly times when a career in films might

well have been ideal for Pilati (e.g., the Forlana in the ‘Three

Pieces’ and the third movement of the ‘Concerto for Orchestra’

when I could almost see an Italian Malcolm Arnold peeping out between

the ravioli and the pasta.

In retrospect I probably made an error when I first

listened to this disc. I decided to listen in chronological order, beginning

with the less representative ‘Suite’ of 1925. My next selection followed

the sequence of the CD with the longest and most impressive work being

the so-called ‘Concerto for Orchestra’. Although the booklet

reminds us of works of similar title by Bartók, Lutoslawski etc,

it also informs us that one of Pilati’s favourite composers in the '20s

was Ernest Bloch who composed his first and best known ‘Concerto

Grosso’ in 1924 (the 2nd not until in 1951). It is the

baroque idea of 'concerto', that informs this piece, with its grand

opening Prelude. The contrapuntal basis of the second and third movements

hides the main theme of the opening but the return of this theme is

the basis for the cyclic nature of the work. The piano at times seems

like a soloist. The E minor second movement is neo-classical in perception

with its ornamentations in the piano, string and wind figurations in

a baroque manner but with romantic harmonies. I personally find the

sound of the piano in the texture unconvincing and it brings to mind

the sound of a theatre orchestra trying unsuccessfully to be serious.

Indeed the scoring in general is a mixture of the Hollywood MGM sound

of the 1930-40s tweaked with reminders that baroque music should be

more hair-shirt than passion.

The ‘Three Pieces’ consist of three dances,

a Minuetto, a Habanera and a Furlana. These are

very attractive works deliciously, nicely and convincingly scored -

the influence of Ravel can surely be heard here. I am thinking of ‘Le

Tombeau de Couperin’ (1917) but also in the Habanera a touch

of ‘La Valse’. There is a colourful use of percussion throughout

especially at the opening of the Furlana. The harmony is rich and was

quite probably was considered rather modern for its time.

The ‘Suite’ is a strongly neo-classical work in which

the piano dominates. The booklet is graced with a lovely sepia photograph

of Pilati and his small orchestra at the time of its first performance.

The Sarabande is a perfect work of its type and style as is the Minuet,

so reminiscent of Ravel and even Fauré.

The disc ends touchingly, with Pilati’s last work,

written as he was literally on his death bed, a ‘Cradle Song’, really

a melancholy Berceuse for one might say, his own slumber. It

is scored for five wind instruments, celesta, harp and strings. It is

a work that should be better known and any readers who work for Classic

FM would find it an ideal advert for the world’s most beautiful music.

The recording is perfectly good and well balanced.

I have little criticism of the orchestra except that the strings seem

to be not quite on top of the demands in parts of the Concerto.

For a number of years now early 20th Century

Italian music has, thanks to Marco Polo, been getting more exposure.

There is so much more to Italian art music of that era than Puccini

and Respighi. Well worth investigating.

Gary Higginson

![]() Slovak Radio SO/Adriano

Slovak Radio SO/Adriano![]() MARCO POLO

8.225156 [61.05]

MARCO POLO

8.225156 [61.05]