Bach's Sonatas for Violin and Harpsichord were the first sonatas to take the harpsichord beyond its role as a simple accompanying instrument and give it a central position in the music. Up until these works, such sonatas would be scored for violin and basso continuo - where the harpsichord and a cello would play "background music" to highlight the violin's central part. Here, however, the harpsichord is specified and given a true instrumental role. Some of the movements in these works are written as trio sonatas, others as fugues, others as three part inventions, and some sound like concertos. The right and left hand parts are not mere filler; they each have their own voices, and these works should be seen as three-part works, rather than two.

This is the approach taken by this recording from the new label Musica Omnia. Harpsichordist Peter Watchorn (one of the principals in the company) sets out with the goal of bringing his instrument to a central position in the soundscape, but, rather than miking it closely to achieve this, uses a very large instrument (a copy of a German harpsichord by Johann Heinrich Harraß) similar to one that Bach may have used.

The effect is brilliant. The clarity of the lines of the harpsichord, added to that of the violin, take this music and give it new life. While the muddy mixes of recordings of these works have often disappointed me, this set has opened my eyes in ways I could not have hoped for. The slow movements take on a new emotion, as in the adagio of the C minor sonata, where the violin merges seamlessly with the triplets of the harpsichord's part. Or the amazing dialogue between the violin and the flowing melody of the harpsichord's right hand part, as the violin accompanies it with its double-stops.

The faster movements contain a level of excitement and energy rarely heard in recordings of these works. The allegro of the E major sonata, with its unique rhythmic energy and, again, the clear presence of the harpsichord's part, is majestic. The vivace, the final movement of the F minor sonata, is wonderful in its quirky sound and rhythm; this three-part fugue gives the harpsichord a very important role, and, at times, the violin follows its lead as the right-hand part takes over.

The two musicians both play excellently. Emlyn Ngai plays a beautiful sounding baroque violin that would be a delight to anyone who fears the often shrill sound of such instruments. Watchorn's harpsichord has a rich, ample sound that gives the lower registers much more body than most harpsichords. Taken together, this is an aural pleasure.

Musica Omnia has come up with an original idea. Each of its recordings contains an additional CD, called Beyond the Notes. This is basically a presentation of the music with spoken text and musical examples. In a way, it can be seen as liner notes with music. While one would not want to listen to this CD many times, it is invaluable in giving the listener a more complete approach to the music. Whether listened to before or after hearing the music, it opens the ears to new insights in a way that printed liner notes cannot. Musica Omnia deserves kudos for this idea, and it would be wonderful if other labels picked up on it. Here, Peter Watchorn gives an overview of Bach's career in Cöthen, where these pieces were written, then goes on to discuss each movement of the six sonatas. This gives the listener much more insight into the music, as Watchorn highlights what is unique in each movement.

Another plus on this recording is the performance of a movement that Bach dropped from the first version of this piece. This movement, marked Cantabile, ma un poco adagio, was later reused as a soprano aria in cantata BWV 120. Listening to this haunting movement, one can immediately hear the violin playing obbligato as the soprano part is played by the right hand on the harpsichord. It is a magnificent piece, and a real delight to hear. (This movement is rarely played, but Rachel Podger and Trevor Pinnock also recorded it on their recent set.)

I look forward to hearing more recordings from this new label, especially the projected recordings of Bach's keyboard works by Peter Watchorn.

This is one of the best recordings available of Bach's Sonatas

for Violin and Harpsichord. The performances by both musicians are excellent,

the balance between them a revelation, and the addition of the Beyond

the Notes disc makes this not only a highly-enjoyable listening experience,

but an enlightening one as well. This is an essential disc for any Bach

lover.

Kirk McElhearn

CONTACT DETAILS

http://www.musicaomnia.com

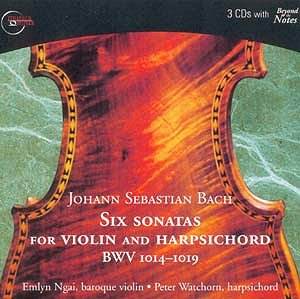

![]() Emlyn Ngai, baroque violin,

Peter Watchorn, harpsichord

Emlyn Ngai, baroque violin,

Peter Watchorn, harpsichord ![]() MUSICA OMNIA MO 0112 [103.30

+ 27.39]

MUSICA OMNIA MO 0112 [103.30

+ 27.39]