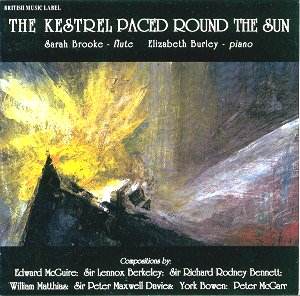

THE KESTREL PACED ROUND THE SUN

Edward MCGUIRE Caprice (1990s)

[2.14]

Edward MCGUIRE Prelude 3 (1985)

[3.35]

Lennox BERKELEY Sonatine (1939)

[9.53]

Richard Rodney BENNETT Winter Music (1960)

[9.32]

William MATHIAS Sonatina (1953)

[7.54]

Peter MAXWELL DAVIES Kestrel Paced Around the Sun

(1976) [6.29]

Edwin YORK BOWEN Sonata (1946)

[18.10]

Peter MCGARR Something Lost (1999)

[12.35]

Sarah Brooke

(flute)

Sarah Brooke

(flute)

Elizabeth Burley (piano)

rec 1997, Rosslyn Hill Chapel,

Halstead

BRITISH MUSIC LABEL BML 032 [70.29]

BRITISH MUSIC LABEL BML 032 [70.29]

Is a whole disc devoted to British music for flute and piano more for the

convenience of the company and the performers than for the delectation of

the listener? Well, there can be little doubt that as a recording project

it is far more cogent and tidy to feature one ensemble and one genre for

each CD. I am sure I recall reading that mixed genre CDs tend to do rather

poorly in the marketplace (eg where you mix solo piano, chamber and orchestral).

The Scottish composer Edward McGuire has not been elevated to the

celebrity of Macmillan or Beamish but this is for extra-musical reasons rather

than any defect in his music. The notes mention his Calgacus and Glasgow

Symphony (orchestral pieces) both of which attained performances and broadcasts

during the 1990s. These two pieces have more in common with the stream of

melody that is his sadly unrecorded orchestral piece Source.

Source spoke of Reichian simplicity without being drawn down too deep

into repetitious puerility. Both works are grace-filled with Prelude

3 being slightly more thorny than Caprice.

Lennox Berkeley is a popular

composer at the chamber and solo level. For me, his music became rather grey

in his later years. There is a vibrancy and danger about his early years'

music that is well worth following up. His Nocturne (brooding with

a Rubbra-like climactic release and still unrecorded but memorably broadcast

in a performance by the BBCSO conducted by Vernon Handley in 1977) as well

as his Overture, Mont Juic dances (with Britten and recorded

on Lyrita SRCD226) and Cello Concerto are works of a more highly coloured

and engaging tack. The Sonatine, originally for recorder, is Frenchified

(Berkeley was a friend of Poulenc), compact and flighty. It compares favourably

with the terse Winter Music of Richard Rodney Bennett.

Winter Music is barbed and brambly in the mood of his Third Symphony

and Violin Concerto. The piano part is stop-start, all-purpose modernism

though never totally losing the melodic track. The flute - the singer - naturally

follows a more engaging line but this remains a piece to take to only after

repeated listenings - nothing amiss with that but just be warned this is

not the Bennett of the recent Chandos film music set.

William Mathias is close

to being a popular composer and I suppose that this is, in many minds,

subliminally legitimised by his death eight or so years ago. My first contact

with his music was of a BBC broadcast of the premiere of his celebratory

anthology cantata This Worldes Joie into which he threw a massive

orchestra, soloists, choirs of children and grown-ups as well as his own

brand of highly-spiced percussion dotted and richly rhythmic tonality. How

fortunate that Lyrita and Nimbus discs make his music so easily accessible.

His trilogy of symphonic movements (perhaps a little like Holmboe in this):

Helios, Laudi and Vistas are easily to be had on disc.

I doubt that he will be easily forgotten or that anyone would want to forget

such a creative imagination. His balm-filled Sonatina was

originally from 1953 and then revised for a fresh premiere with William Bennett

in 1986. It is subtle, fragrant, rest-filled and divertingly playful. Balm

after the Bennett; balm before the late 1970s

Maxwell Davies. Max's

Kestrel

(sadly another misprint in the booklet to match the insistence on

'Matthias' instead of the correct 'Mathias') was inspired by Peat Cutting

a poem by George Mackay Brown. In it the Kestrel, lord of the peat bog, wheels

high above the cutters leaning on their tuskars (peat cutting implements).

Another Orcadian work, the music is virtuosic and apparently based on material

from Max's First Symphony. You may well recall the First Symphony as a massive

work memorably recorded at the time by Decca Headline. It is a startlingly

Sibelian piece though no mere pushover - for if it is Sibelian it is the

Sibelius of the Fourth Symphony and that through a carbonised mirror -

emphatically not of Karelia. The movements of this piece were written

between the movements of the symphony.

We know we are back in tonal hands with York Bowen. He is a notable

romantic from the Royal Academy displaying Corder's rhapsodic Tchaikovskian

line rather than the Brahmsian models of Stanford and Parry (from the Royal

College). A contemporary of Bax, another RAM student, he lived until 1961

(not 1969 as the BML's notes consistently and wrongly insist) surviving Bax

by eight years. By that time however he felt even more of an anachronism

with his music needing special pleading and relying on birthdays and

anniversaries for attention from the BBC. A Lyrita mono LP of the elderly

composer playing a selection of his piano music was due to Richard Itter's

foresight and is very much the exception. Bowen, however, had one signal

advantage over Bax in terms of exposure among musicians and that is the great

flood of accessible music he produced for piano and for various duos. This

latter factor kept his music in use by musicians and in recital programmes.

The fluent Flute Sonata is an example. The notes are at fault in not

mentioning that there are four (not three) piano concertos - the last dating

from the 1930s and being a large-scale work of an ambition and, up to a point,

a consummation that is faithful to Rachmaninov as were the 1930s and 1940s

piano concertos of Reginald Sacheverell Coke. The sonata was written in 1946

for Gareth Morris. It is lovingly turned by Sarah Brooke who is attentive

and sensitive throughout this recital. The Sonata is somewhat in the Baxian

track with the piano part recalling Sergei (R not P). It is a big piece -

no mere bon-bouche. This is the longest work on the disc at 18 minutes and

it is also the one in which the composer avoids any suggestion of responding

to the flute as an exhortation to perfumery. This might easily have served

as a violin sonata. There is a piacevole middle movement and a cheerful

finale with sufficient gravity that it counterbalances the big first movement

which is twice as long. If you needed to pick and choose between this version

and the Kenneth Smith version on ASV CDDCA862 you would need to choose on

basis of the coupling. The recording is clarity itself preserving a fruity

tone.

Peter McGarr wrote his sun-slowed piece for the two soloists on this

disc. Like the Maxwell Davies it is prompted by poetry - this time Philip

(proof-reading at fault in the 'Phillip' in the notes) Larkin's 'Love Songs

in Age'. While modern (1999) this piece which is the second longest on the

disc (in ten sections not separately tracked) is sentimental and a slow blooming

delight - easy to appreciate rather like a cross between the vernal works

of Nino Rota (the slow movements) and Samuel Barber (Knoxville). I

loved this piece.

The spelling errors in the otherwise desirable model-clear booklet are

aggravating (hyphernated' for heaven's sake!) to pedants like yours truly

but don't let that trivial factor detract from the real pleasure to be had

from this disc. It is a serious recital and its variety is lovingly advocated

by both performers aided by Mike Skeet's airy and juicy recording.

Rob Barnett

UK is £10 incl UK P&P

abroad, the appropriate extra - Please approach Mr Skeet for quote.

Mike Skeet at F.R.C.

44 Challacombe

Furzton

Milton Keynes MK4 1DP

phone/fax +44 (0)1908 502836

email:

mike.skeet@btinternet.com

www.skeetmusic.com