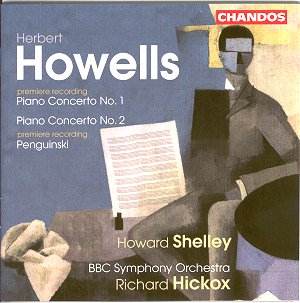

HERBERT HOWELLS

Piano Concerto No.1 in C minor Op.4

Piano Concerto No.2 in C major Op.39

Penguinski

Howard Shelley, piano

Howard Shelley, piano

BBC Symphony Orchestra/Richard Hickox

CHANDOS CHAN

9874

CHANDOS CHAN

9874

Crotchet

Herbert Howells is generally best-remembered for his organ works and his

choral music which includes some large-scale choral/orchestral pieces. One

tends to forget that quite a number of his early works were either instrumental

or orchestral ones.

CHANDOS's earlier releases (Orchestral Works Volume 1:

CHAN

9410 Volume 2:

CHAN

9557) together with the present disc help put things straight again and

make one regret that, for whatever reasons, Howells did not write any purely

orchestral music after about 1940. (Incidentally Music for a Prince of 1948

is just a reworking of two movements from the early suite The Bs.)

Howells' three big orchestral works - if one excepts the magnificent

Concerto for Strings - are concertante pieces: the two piano concertos

and the masterly and long-forgotten Fantasia for cello & orchestra.

Moreover the First Piano Concerto was completed in 1913 when Howells was

still at the RCM. Stanford conducted its first - and possibly last - performance

with Arthur Benjamin as soloist in 1914 at the Queen's Hall. Ivor Gurney

obviously loved the piece and longed to hear it again. He was never to do

so. The First Piano Concerto is a most ambitious piece lasting over half

an hour cast in the grand romantic mould with a lengthy first movement including

an extensive cadenza, a long meditative slow movement and a more animated

finale. One might be forgiven for hearing echoes from Rachmaninov, Schumann

or Brahms in this youthful work which already displays a remarkable orchestral

flair and assurance in its handling of long paragraphs. Quite an achievement

for a composer still in his early twenties.

The score of the First Piano Concerto used for the present recording was

prepared by John Rutter who completed the missing final bars and to correct

some errors in the parts and score.

The Second Piano Concerto, of which this is the second recording (Hyperion

CDA66610),

shows a considerable advance on No. 1. By now Howells had found his way into

music and was fully master of his trade. He devised his Second Piano Concerto

in the grand romantic manner although this now clearly Howells' throughout.

The first performance was not altogether a success. The soloist, Harold Samuel,

disliked it and the conductor, Malcolm Sargent, was not particularly fond

of it. This disastrous premiere came as a blow to Howells and probably caused

him to cease writing orchestral music.

Howells described this Concerto as having "deliberate tunes all the way"

and "being jolly in feeling, and attempting to get to the point as quickly

as may be". Of course, with Howells, things are not always as simple as that.

The music of the concerto has many Howells fingerprints but the accusation

of "modernism" heard at the time of the first performance does not hold if

put into the context of the present times.

This bright, brilliant and dynamic piece may now be enjoyed for what it is

- a beautifully crafted, colourful work likely to appeal to audiences that

enjoy, say, Ireland's Piano Concerto or Prokofiev's Third Piano Concerto.

There is not much to choose between the present performance and that by Kathryn

Stott with the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Vernon

Handley (HYPERION CDA 66610 ). Hickox tends to favour somewhat slower tempi

in the first two movements while he makes the Finale really joyful.

Stravinsky's Petrushka was a lasting influence on Howells' orchestral

music which often has some sort of concertante piano part. Clearly

Penguinski is yet another homage to Stravinsky (even in its title!).

This short ballet is a delightful trifle well worth hearing. It is a fine

example of Howells at his most extravert. It was written for a visit made

by the then Prince of Wales to the RCM. Incidentally Paul Spicer in his excellent

insert notes mentions 1933 as the date of this visit whereas Christopher

Palmer (in "Herbert Howells: A Celebration" Thames 1996 2nd edition) mentions

1929. Can anyone shed any light on this small documentary point?

Howard Shelley plays with assurance and affection, and receives a superb

support from the BBC Symphony Orchestra conducted by Richard Hickox. So I

do not hesitate in recommending this most welcome addition to Howells' steadily

expanding discography, mainly thanks to enterprising record companies such

as CHANDOS and HYPERION. I hope there will soon be a fourth volume.

Hubert CULOT

A belated response to a question posed

by Hubert Culot in his review of the disc including the brief ballet

'Penguinski' by Herbert Howells. Hubert asks about the discrepancy in

dating this work between Paul Spicer's booklet note (1933) and Christopher

Palmer's book 'Herbert Howells: a celebration' (1929). Spicer is correct.

I compiled the works list for Christopher's book as an ofshoot of a

long and ongoing project to document Howells' music. Penguinski is one

of several works by Howells about which there has been some confusion,

a situation often exacerbated by the innacuracy of the composer's own

memory in his old age. We took the date from an earlier source, based

on a conversation with Howells himself. At the time all that existed

of the piece was an undated and incomplete sketch. We knew that it had

been written for a specific occasion at the Royal College of Music,

but the actual date of that concert was not unearthed until after the

publication of Christoper's book. Later still, a complete and intact

set of parts was uncovered - presumably those from the first and only

performance - and this formed the basis of the score that was made up

for the Hickox recording. Needless to say there were discrepancies between

the parts and the sketch, but we took the parts to represent Howells'

last thoughts on the matter.

Paul Andrews

p.d.andrews@btinternet.com