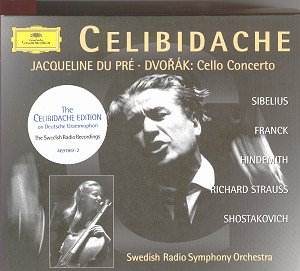

CELIBIDACHE

The Celibidache Edition

Dvorak: Cello Concerto,

Franck: Symphony in D minor,

Hindemith: Mathis der Maler

Sibelius: Symphonies Nos. 2 and 5,

Strauss: Till Eulenspiegel, Don Juan

Shostakovich: Symphony No. 9

Swedish Radio Symphony

Orchestra/Jacqueline du Pré

Swedish Radio Symphony

Orchestra/Jacqueline du Pré

Recorded 1965-1971

DEUTSCHE GRAMMOPHON 469

069-2 4 CDs [257'

14"]

DEUTSCHE GRAMMOPHON 469

069-2 4 CDs [257'

14"]

Crotchet

£49.95

Amazon

UK £55.99 AmazonUS nya

Sergiu Celibidache (1912-1996) was a flamboyant, charismatic conductor and

a musician of strongly held convictions. He was a meticulous rehearser, usually

from memory and that not only due to failing eyesight but also because there

was nothing he did not know about every detail of the music he was preparing

for performance. He insisted on so many rehearsals ('his musical standards

border on the inhuman', observed an adoring orchestral player) that few

orchestras could afford him ('there is no miracle in music, only work' he

would assert to justify his demands). He pointedly refused to conduct opera

because it meant making too many compromises. He was also an implacable foe

of the gramophone record. For Celibidache listening to a recording of a great

piece of music was 'like going to bed with a photograph of Brigitte Bardot'.

His view of the performance of music was encapsulated thus, 'Music arises

out of the moment, and this moment cannot be fixed or repeated'. His speeds

were judged according to several precepts and conditions including the complexity

of note values (he loathed the metronome), their epiphenomena (in other words

the sounds which appear from the division of the main note after it is played),

and the acoustical properties of the hall in which the performance was taking

place ('time is space'). Many consider his speeds too slow but most concede

that he was capable of producing immaculate articulation, brilliant detail

and vivid colours. His eye for phrasing and his ear for balance was everywhere

in all he conducted.

After his death his widow and son decided to grant permission for his

performances to be put on CD and a flood of live recordings of concerts has

emerged during the past five years. EMI have released his concerts with his

last orchestra, the Munich Philharmonic, whilst DGG have his earlier encounters

with two other orchestras he headed, the Stuttgart Radio Symphony Orchestra

(who could afford to give him plenty of rehearsal time) on discs from the

late 1970s and early 1980s, and with the Stockholm-based Swedish Radio Orchestra.

Unfortunately this set is the first not to include a CD of him rehearsing,

which often proved as revelatory as the results. Celibidache was only briefly

in Stockholm, between 1965 and 1971, but left his mark with both players

and public alike. Significantly he had few encounters with soloists (a marked

exception was Michelangeli), personality clashes generally produced unhappy

results but not with Jacqueline du Pré, who came to Sweden for two

performances of the Dvorak cello concerto in November 1967, and the two got

along well. Her unmistakeable sound with its quintessential physical attack

at her first entry mark a striking encounter between two musical phenomena.

He insisted on (and got) a piano rehearsal followed by three or four sessions

with her and the orchestra, for his view was that the orchestra was not a

servile accompanist but one half of a musical partnership. The result was

a chamber music-like approach; her playing is intensely romantic and while

phrases hang in the air (such as in the wonderful duet with the clarinet

in the finale), the vibrato she uses has passionate warmth. The portamento

sometimes seems old-fashioned but it all falls into place in the amazing

clarity of both artists' musical thought in the Adagio. Du Pré clearly

loved this music almost as much as her beloved Elgar concerto, and the result

is flawless playing. Celibidache had an amazing capacity to make the listener

come fresh to a work, however familiar it may appear to be, but in this instance

we have the glorious playing of Du Pré as well.

What a pity DGG could not have filled the thirty minutes left on this CD

with either some of the rehearsal of the concerto (if any of it was indeed

recorded) or another work conducted by Celibidache. They were far more generous

in eighty minutes of Sibelius, a bubbling account of the youthful second

symphony with its skittish woodwind choruses and blazing brass. This recording

(1965) was made early in the six year partnership between the SRSO and

Celibidache, whilst that of the fifth (1971) clearly shows the difference

he made to the orchestra during his tenure as conductor (he forbade the

designation of his appointment to any orchestra as Chief Conductor). Not

only has the playing quality significantly improved, but ensemble has unified

and the sound taken on more refinement. This is not to denigrate the playing

of the second symphony, there are magical moments aplenty, in particular

the hushed pianissimo the strings achieve at times in the Adagio.

Every programme Celibidache conducted with the Radio Orchestra had to have

a week's rehearsal (hitherto only two and a half days including the dress

rehearsal were allocated) and it shows, particularly in the playing two of

Strauss' tone poems. His detailed work would probably be neither tolerated

not affordable today but in his superbly graphic reading of Till

Eulenspiegel the solos are all immaculately refined in true Straussian

style from that nerve-wracking solo horn passage to the leader's rapid descent

of Till sliding down the bannisters, and the strangulated shrieks of the

E flat clarinet as he goes to the gallows. It is exhilarating playing, and

you can tell what's going on without knowing the story of Till's merry pranks.

Don Juan gets off to a frenetic start but the performance (recorded

in Nuremburg during a tour by the orchestra of Germany in November 1970)

develops into a highly sensuous one with a glorious climax. En route Celibidache

is always considerate for the orchestral solos excellently taken by his leader,

principal oboist, clarinettist and horn player. The degree of accuracy in

this performance of a work notoriously prone to accidents at any point along

the way simply goes to show the extent of Celibidache's meticulous rehearsing,

while his way of drawing the listener's ear through the textures makes for

compelling listening. Coupled with this pair of tone poems is Shostakovich's

quixotic ninth symphony, the 1945 creation expected to celebrate the Russian

part of the victory at the end of World War II. Instead the result is a huge

musical tongue in cheek, full of acerbic wit and acid humour. Celibidache's

view of the work is given in this clean cut performance (March 1971) full

of biting parody and wistful melancholy.

The familiar Franck symphony is easy meat for Celibidache, whose favoured

interpretations of both French and German music find a comfortable synthesis

in this Wagner-influenced work. He succeeds in drawing out the elegance of

the phrasing, while once again giving both space and breadth to his players

in their respective solos. For his powerful interpretations of music from

the German repertoire, turn to the EMI set of Bruckner symphonies or the

DGG Brahms cycle, but Celibidache also had a special affinity of a contemporary

German composer, Paul Hindemith. Furtwängler took a defensive stance

against the Nazis over Hindemith's 1934 opera Mathis der Maler and

paid the price with the loss of his post as State Music Director, while

Celibidache did not have to make such a sacrifice when he conducted most

if not all of the composer's orchestral output. His interpretation is

unsurprisingly full of powerful conviction, drawing on the strengths of the

work's vivid orchestration and, in places, its contrapuntal infrastructure.

Celibidache, unlike Stokowski, was not one for effects but a conductor whose

conviction and drive was both purposeful and unshakeable in the pursuit of

interpretation. There is never a moment when your attention will wander when

listening to this man's musicmaking.

Christopher Fifield

Performance

Recording