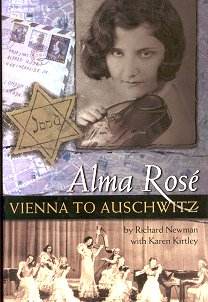

ALMA ROSÉ: VIENNA TO

AUSCHWITZ

By Richard Newman with Karen Kirtley

Amadeus Press. 400 pages. ISBN 1-57467-051-4

AmazonUK

£22.50

AmazonUS $20.96

Alma Maria Rosé was born in 1906 to Viennese "musical royalty". Her

mother was Gustav Mahler's sister Justine and her father was Arnold Rosé,

for over fifty years the Concertmaster of the Vienna Philharmonic and State

Opera Orchestras and leader of the legendary Rosé Quartet. Alma, named

after her Aunt who was Uncle Gustav's wife, first knew only a world of music

and a world where music making meant renown and privilege. The early part

of this book details this lost world as almost a "Who's Who" of musical Vienna

seemed to spend time it's in the Rosé household. By the very end of

Alma's story, however, music would have become the difference between life

and death.

Alma grew up beautiful, clever and talented as a violinist like her father.

When she married the Czech violinist Vasa Prihoda in 1930 the two went on

tours together. Even though he appears to have been given more of the attention,

Prihoda still resented Alma's presence, resented the name of his famous wife,

not to mention her getting in the way of his philandering and the tours tailed

off. Then in 1932, in a bizarre pre-echo of what would be her eventual fate,

Alma founded and led an all-woman orchestra, "The Vienna Waltzing Girls".

They were a big draw with audiences. Leaving aside the fact that this was

a top class string orchestra, the fact that they were also pretty girls in

flouncy frocks guaranteed attention and Alma had a winner.

Her family was Jewish but Arnold Rosé cared little about religion.

Like many assimilated Jews of his musical circle his art was his god. Though

baptized as a Protestant and then converted to Catholicism when she married

Prihoda, Alma also appeared to be of the same mind as her father. But this

was now Europe in the 1930s, Nazism was spreading, anti-Jewish laws were

soon enacting the resurgent anti-Semitism always beneath the surface in Europe

in the first half of the 20th century and the Nazis determined who was Jewish

and who was not. In the end "The Waltzing Girls" found their dates gradually

being canceled causing them finally to fetch up penniless in Munich in 1933

where Prihoda had to pay their debts to get them back to Vienna. Two years

later Prihoda and Alma divorced and new Nazi racial laws meant the days of

"The Waltzing Girls" were numbered. When Hitler turned the screw on Austria,

Jewish musicians found it harder and harder to perform and by 1938 the group

disbanded completely. Alma still worked in Holland but the sky was darkening

and she decided to get her aging parents out of Europe altogether.

Enlisting the help of her old friend Bruno Walter, she got her father to

England just after the death of her mother. Alma even came to London with

the old man but then fatally went back to Holland to carry on working as

a virtuoso, even staying when the Nazis came, playing in private homes to

earn enough to live. When the Nazis inevitably decided to clear Holland of

all Jews she tried to cheat the SS but, in the end, while attempting escape

to Switzerland, she was betrayed, captured and sent to Auschwitz. Had it

not been for her musical ability she would have become victim of the medical

experiments of the infamous Dr. Josef Mengele. But fate had other ideas.

Saved by her name and talent she was appointed director of the recently formed

women's orchestra in the camp.

For ten months she shaped a large number of starved and terrified girls into

a brilliant orchestra using whatever talent they had in whatever instruments

they could play on. Mozart played on accordions and mandolins, as well as

violins and pianos, for example. So impressed were the camp masters by Alma's

exacting standards that visiting Nazi leaders were given special performances

by this remarkable ensemble whose fame spread through the hierarchy of the

"new order". By doing so Alma undoubtedly saved the lives of her players

because if they played and played well they would not be sent to the gas,

or Dr. Mengele. It was as simple as that. That Alma herself did not survive

the camp with the fifty or so women she inspired and who owed her their lives

was probably due to one of the many ironies that cut through this story.

Among "privileges" granted her and her musicians by the camp for what they

did was better food rations. At a special dinner given for her by Nazi guards

she seems to have contracted botulism from a contaminated can of meat and

died from it in April 1944. One final, appalling irony then remained. One

of the doctors who tried to save her was Josef Mengele himself. After her

death, after she was laid out honorably on a catafalque, he came to see the

woman whose music making had moved him to tears many times. A singer with

the orchestra, Fania Fénelon described the visit: "Elegant, distinguished,

he took a few steps, then stopped by the wall where we had hung up Alma's

arm band and baton. Respectfully, heels together, he stood quietly for a

moment, then said in a penetrating tone, 'In memoriam.'" That is one

of many contradictions you are forced to face in the course of this book.

In "Playing for Time" Fania Fénelon wrote of her own time as a member

of the women's orchestra in Auschwitz, leading to her survival. But Fénelon

had entered the camp after Alma Rosé and came to see her as little

more than a tyrant and so left a very unsympathetic view that was skewed

and biased. For example, Fénelon knew nothing of what Alma had been

through prior to Auschwitz and, crucially, her early days in the camp. Especially

she knew nothing of Alma's courage in standing up to the SS with the certainty

that whatever she did would save many lives. But you can read it all now

because Richard Newman was a friend of Alma's brother Alfred who, in Canada

long after the war ended, discovered a large collection of Alma's letters

that paint a different portrait from that of Fénelon. Newman also

heard from Alfred Rosé's widow a story that an Auschwitz survivor

that his sister had indeed saved the lives of many Jewish and non-Jewish

girls in Auschwitz by her courage. And this is the touchstone for this book

in which Richard Newman with Karen Kirtley set out to put the record straight

about their subject at last. Their attention to detail, thorough research

over many years and painstaking zeal to piece together the tatters of evidence

that remain to get as close to the truth as possible is as compelling and

moving as the story that emerges. Their detailing of daily life in the corner

of Auschwitz that the women occupied is especially impressive in its grotesque

detail. This is not hagiography, though. It's a rounded, warts and all portrait

of a life whose appalling end inspires as well as saddens beyond words. Not

an easy book to read, principally because you know from the start how it

will end, throwing the carefree glitter of the earlier episodes into tragic

relief. But read it you should.

A true story brilliantly told where music comes to mean the difference between

life and death and where life is stranger and crueler than fiction could

ever be.

Tony Duggan