The following reviews were first published in the British Music Society

newsletter and are published here with M. Culot's very kind permission. Rob

Barnett:-

ALWYN. Symphony 5 "Hydriotaphia"

(1973); Sinfonietta for Strings (1970); Concerto

2 for Piano and Orch (1960) Howard Shelley, piano; LSO/Hickox

CHANDOS CHAN 9196

Alwyn's Symphony No. 5 came many years after his fourth. In the meantime

he devoted much time to other works, especially his two operas, Juan or

The Libertine and Miss Julie. It shows a considerable evolution

in his symphonic manner though retaining many of his fingerprints. It is

much shorter, and more tightly knit than its predecessors and the scoring

is more imaginative than ever. Along with the Sinfonietta and his String

Trio, it is among his more significant pieces. Commissioned by the Arts Council

for the 1973 Norfolk and Norwich Triennial Festival, the Fifth Symphony is

dedicated "to the immortal memory of Sir Thomas Browne, author of a great

elegy on death 'Hydriotaphia: Urn Burial'". Each section is headed by a quotation

from Hydriotaphia, but the work is not programmatic.

As usual in Alwyn's symphonies, Symphony 5 is based on a motto, present

throughout the piece under various guises, ensuring coherence of the musical

material. Alwyn's other masterpiece, the superb Sinfonietta for Strings

also appears, belonging to roughly the same period but is very different.

The diminutive title is misleading; the symphonic argument is as tight as

ever and any composer, less modest than Alwyn, would have happily entitled

it 'Symphony'. It may be Alwyn's most densely contrapuntal piece whose language

is tenser and sparer than in most of his other works. It is sombre and elegiac.

The string writing is forceful, athletic, sometimes reminiscent of Honegger.

The deeply felt slow movement includes a quotation from Alban Berg's Lulu

woven effortlessly into the typical Alwynian fabric. After a nervous

start, the finale is curiously slow and ends with a quiet questioning coda.

A full body of strings is called for and the LSO, in top form, give it a

full-blooded performance.

Piano Concerto 2 was written for the Dutch pianist, Cor de Groot who

had first performed the Twelve Preludes of 1957. De Groot's sudden paralysis

prevented its performance, planned for the Proms. It was put aside and has

never been performed. Alwyn seems to have worked on it some time later, cutting

out the slow movement and replacing it with a short bridge passage between

the outer fast movements. Alwyn restored the original Andante and so had

to rework the end of the first movement. This is the version used on this

disc. The work, unmistakably Alwyn throughout, is traditional with a popular

appeal that could have made it a huge success with Proms audiences. It is

well worth hearing but may not be among Alwyn's best works. When I visited

him in 1984, he confirmed the existence of the work but saying little about

it. Howard Shelley plays the concerto with the utmost conviction and gets

strong support from the LSO.

© Hubert Culot.

ALWYN Symphony 3 (1955/6);

Concerto for Violin and Orch. (1937/9) Lydia Mordkovich,

LSO/Hickox. CHANDOS CHAN 9187

This release couples two major Alwyn works. The concerto considered by Sir

Henry Wood for Prom performance lay forgotten for nearly fifty years. It

plays some forty minutes. Big in size and content. The first movement is

the longest and weightiest. A big orchestral introduction heralds the soloist's

first entry. The violin then has the main argument with vital orchestral

contributions. The end is quiet so that the transition to the slow movement

is smooth, emphasising the work's global concept. Flowing tunes abound,

particularly in the slow movement - a song without words, characteristic

of so many of Alwyn's. The third movement begins quite fast, alla marcia,

leading to a first powerful climax (the theme here bears a resemblance to

that of the finale of Ireland's Piano Concerto). Moderate tempo is resumed

and maintained with abrupt orchestral outbursts. A second bright climax leads

to a brilliant conclusion. The work, shows the way to the 1949 Symphony No

1 with which it shares characteristics: weight of argument, abundance of

ideas, sureness of touch and above all flawless musicality. Why has such

a masterly work remained unperformed for nearly fifty years? Mordkovich is

superb and the orchestra play with conviction and confidence.

Symphony 3 is a major work of Alwyn's maturity and the most dramatic of his

symphonies. There is devastating energy and the outer movements teem with

furious outbursts, verging on violence. The beautifully appeased slow movement

provides respite before the onslaught of the warlike final movement where

Holstian echoes can be spotted. This dissolves in a peaceful epilogue ending

with an abrupt question mark. The work's tension remains unresolved. Perhaps

Alwyn's most pessimistic work, it was written under the shadow of the Cold

War when another world conflagration was possible. A glimpse into Alwyn's

personal brand of serialism is revealed. Sir Thomas Beecham first performed

the symphony to a good reception by critics and audience. John Ireland considered

it the best British symphony since Elgar's Second. Hickox and the LSO seem

to share the view for they perform this deeply personal masterpiece superbly.

Chandos's recording does full justice to Alwyn's masterly scoring.

Hubert Culot

ALWYN Symphony No 2 (1953);

Overture to a Masque (1940); Symphonic Prelude The Magic

Island ( 1952); Overture Derby Day (1960);

Fanfare for a Joyful Occasion (1948). LSO/Hickox. CHANDOS

CHAN 9093

Most pieces on this record have been available earlier (Lyrita and Unicorn).

The novelty here is the comparatively early Overture to a Masque

completed in 1940, not performed then for obvious reasons. It has never

been performed; the score was recently found in the LSO archives. This enjoyable

short piece belongs to the British 'main stream music' of that period. It

is expertly written and brilliantly orchestrated and, listening to the next

item in this CD, the much later symphonic prelude The Magic Island

written for Sir John Barbirolli and the Hallé, one can appreciate

the evolution of Alwyn's writing. The scoring of the prelude is more imaginative

and resourceful than the earlier work. The overture Derby Day was

written in the wake of Symphony No 4, completed in 1959. Another short colourful

work, it could, heard more often, become popular with audiences. Both The

Magic Island and Derby Day belong to Alwyn's maturity and show

a clear stylistic progress and a richer orchestral writing compared to the

Overture to a Masque. Fanfare for a Joyful Occasion is scored

for brass and percussion. A delightful, brilliantly written work it has many

nice instrumental details, especially in the percussion. It provides a bright

conclusion to a very fine CD.

Symphony No 2, the major item, was written for Sir John Barbirolli and the

Hallé who premiered the Symphony No 1 (1949) and The Magic

Island. It is much shorter than its predecessor but is possibly the best

example of Alwyn's symphonic thinking. Most of the material derives from

the bassoon theme of the very first bars of the first movement. A few other

elements stated from the early stages of the symphony also play an important

part, giving clear coherence to the symphonic argument throughout. The work's

beautiful epilogue is entirely based on the bassoon theme played in turn

by strings, woodwind and finally by the brass as a chorale. Symphony No 2

is a tightly argued work full of fine moments. It is easy to see why it was

the composer's favourite symphony.

The fourth release in Chandos's Alwyn cycle, this is of the same excellent

quality as the earlier ones. The LSO is in fine form throughout. Brass and

percussion are superb in the brightly scored Fanfare For A Joyful

Occasion. This CD also offers the first performance and recording of

an early work that is well worth unearthing and likely to appeal to audiences.

Richard Hickox again confirms his sympathy for and understanding of Alwyn's

music.

© Hubert Culot

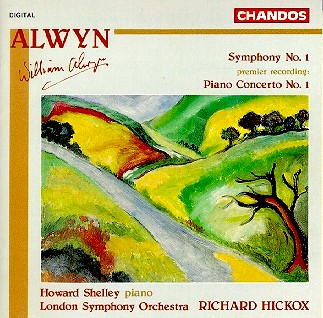

WILLIAM ALWYN Symphony 1

(1944) Piano Concerto 1 (1930) Howard Shelley, piano;

LSO/Hickox CHANDOS CHAN9155

Of many disowned pieces, Alwyn apparently considered his first piano concerto

the best of them. The concerto, written for and premiered by Clifford Curzon

with the Bournemouth SO conducted by the composer, is a fine work. Influences

are easy to trace: Prokofiev and Ireland appear but the work exhibits too

a quite remarkable sureness of touch, especially in the orchestral part,

already signalling Alwyn's mature writing. The one movement work falls into

four clear sections: an energetic opening allegro domino is followed by a

slow section leading to a varied restatement of the opening music immediately

followed by a peaceful epilogue ending with a sustained string chord, perhaps

the most remarkable part of the whole. The work may be Alwyn's first most

significant work and worthy of revival. It is superbly performed and will

surely earn new sympathies.

Symphony 1 was completed at least twenty years after the piano concerto.

Meanwhile, Alwyn had written much film music, gaining technical mastery of

a broader orchestral palate, evident in this symphony. There are still

influences, notably that of Sibelius, but - more importantly - Alwyn's mature

symphonic manner (to be further refined over the years culminating in Symphonies

4 and 5 "Hydriotaphia" and the Sinfonietta for Strings) is affirmed. There

are four movements, an energetic scherzo placed second. Among the many Alwyn

fingerprints is the use of germinal cells on which the rest of the symphony

builds. Thematically rich, the work has many instrumental felicities, instanced

by the magnificent horn tune in the second movement. The slow movement is

a simple ABA form and essentially song-like in character. It is based on

two main themes: the first stated by the cor anglais after a 3-bar introduction

given by the horns and the second one by the violas somewhat later. This

theme dominates most of the movement. Alwyn described the fourth movement

as "probably the most extrovert piece (I have ever) written". The themes

almost run riot and the music is rushed to a brilliant conclusion.Hickox's

reading of the work is fine - further proof of his affinity with and feeling

for Alwyn's music. The LSO play well throughout. © Hubert Culot.

WILLIAM ALWYN. Concerto for Oboe,

String Orch & Harp (1944/5) Concerti Grossi 1 in B flat

(1943) 2 in G (1948) 3 (1964).

Nicholas Daniel, oboe; City of London Sinfonia/Hickox CHANDOS CHAN 8866

Symphony 4 (1959) Elizabethan Dances (1956/7)

Festival March (1950) LSO/Hickox CHANDOS CHAN 8902

These first two CDs of an Alwyn cycle planned by CHANDOS should yield many

riches, including a number of hitherto unrecorded works as well as some already

commercially available. Issue 1 offers three firsts; all the Concerti Grossi,

except C.G.2 are new to recording. C.G.1 is dedicated to 'my friends in the

LSO". It is the earliest item preserved by Alwyn who discarded most of his

pre-1940 works, and a rare example of Alwyn's neo-classicism which he was

soon to abandon. A vigorous fanfare-like first movement is followed by a

delicately-scored Siciliana. This delightful work closes with a Vivace "with

a restatement of the original trumpet theme on the full orchestra". The Concerto

for oboe, string orchestra and harp is one of Alwyn's few excursions into

the pastoral mood once favoured by some British composers. It is in two movements

played without a break: the first, a Moderato with a more animated middle

section, leads into a dancing Vivace. This beautiful short work deserves

more hearings.

William Alwyn recorded his C.G.2 with the LPO (LYRITA SRCS 108). It is scored

for strings including a solo quartet and is beautifully laid out for them.

The fine slow movement has the quartet in dialogue with the full body of

strings and is lyrical in Alwyn's finest vein. These beautiful works definitely

deserve more hearings . Subtitled 'Tribute to Sir Henry Wood' the C.G. 3

is a short, enjoyable work containing forceful brass writing and many fine

moments for strings an woodwind. It is virile, devoid of any neo-classical

gestures and ends with a deeply-felt Andante.

The second disc groups three very different works belonging to the same decade.

The Festival March was written for the 1951 Festival of Britain. It follows

the pattern of Elgar's and Walton's marches, but Alwyn remains himself. The

Elizabethan Dances were written for the 1957 Light Music Festival and show

Alwyn's lighter side. This is superbly-scored music and the whole set is

another example of Alwyn's orchestral flair and mastery. These dances could

be as popular as Arnold's various dance sets, though less flamboyant. Both

the Festival March and four of the Elizabethan Dances (1,2,5,4 [sic]) were

recorded by Alwyn (respectively LYRITA SRCS 99 and SRCS 57); the present

recording is the first of the complete set.

The 4th Symphony is in three movements of fairly equal length: the first,

Moderato, the second a longish Scherzo and the third another Moderato. Thus

the plan bears some resemblance to Rubbra's 7th of 1957. All three movements

are dominated by a motto heard at the outset, a practice already present

in Alwyn's earlier symphonies. The conflict, started in the course of the

first movement, gets more power in the restless Scherzo, while the third

movement, a Passacaglia, brings the work to a triumphant conclusion in which

the ostinato from the scherzo, briefly restated, launches the epilogue which

ends on a bright chord.

All five Alwyn symphonies, his Sinfonietta and Harp Concerto - "Lyra Angelica"

- and some shorter works were recorded by LYRITA in a mini-cycle, all played

by the LPO under the composer. These recordings were superb and still sound

well. The composer's conducting lent authenticity to the fine performances.

Hickox's readings are along similar lines. He conducts all the works with

his customary understanding, sympathy and commitment. His performance of

the 4th Symphony is superb throughout and the warmth of the recording suits

Alwyn's lyricism. Both orchestras are fine and the LSO play the music of

their former colleague with affection, conviction and assurance. The standards

of recording and production are up to CHANDOS's highest; they are to be thanked

and congratulated for this large-scale enterprise that might prove as significant

as their Bax and Walton series Newcomers to Alwyn might start with the Concerti

Grossi CD since that provides a useful survey of Alwyn' s progress between

1940 and 1960. Others will need no further recommendations to get both discs

and look out for further releases in this major venture.

Hubert CULOT

WILLIAM ALWYN

Odd Man Out Suite (1946)

The History of Mr Polly Suite (1949)

The Fallen Idol Suite (1948)

Calypso from "The Rake's Progress" (1945)

London Symphony Orchestra - Richard Hickox

CHANDOS CHAN 9243

String Quartet No.1 in D minor (1955)

String Quartet No.2 "Spring Waters" (1975)

Quartet of London

CHANDOS CHAN 9219

Invocations (1978)

A Leave-Taking (1977)

Jill Gomez, soprano - John Constable, piano

Anthony Rolfe-Johnson, tenor - Graham Johnson, piano

CHANDOS CHAN 9220

Fantasy-Waltzes (1955)

Twelve Preludes (1957)

John Ogdon, piano

CHANDOS CHAN 8399

The last three records under review were first issued in LP format in the

1980s and late 1970s.

The first string quartet is an outstanding example of Alwyn's lyricism and

stylistically belongs to the same period as the THIRD SYMPHONY and the FOURTH

SYMPHONY. It is in four movements of which the wonderful slow movement is

the emotional heart. The second string quartet, subtitled "Spring Waters",

is a very different piece. It is in turn more uneasy, restless, sharp-edged,

more violent and aggressive than its predecessor. It is also imbued with

bitter-sweet feelings foreign to the lyrical mood of the first string quartet.

Even the big unison near the end of the third movement does not sound as

triumphant as the composer might have wished. The performances by the Quartet

of London are very fine and it was their superb first performance of the

second string quartet that induced the composer to write another quartet

for them. This would materialise a few years later when Alwyn completed the

third string quartet which they first performed in 1984.

Alwyn composed several song cycles each as a homage to the singers who took

part in the original broadcast performance of his opera MISS JULIE. A

LEAVE-TAKING to words by Lord de Tabley was written for Anthony Rolfe-Johnson

whereas INVOCATIONS to words by Michael Armstrong was composed for Jill Gomez.

Alwyn's song writing at its best may compare with John Ireland's and some

of the songs are on a grand scale. Both song cycles receive superb performances

from singers and pianists alike, for the piano parts are far from being mere

accompaniments. There is a slight difference in acoustics between these

recordings, A LEAVE-TAKING being given a much more natural balance than the

other cycle. Anyway it must be said that this release is a very fine one

indeed and a worthwhile addition to Alwyn's discography.

Alwyn wrote four large-scale piano works. The FANTASY-WALTZES of 1955 benefits

from John Ogdon's wonderful playing. Ogdon's sympathy with the music is evident

throughout and he obviously relishes Alwyn's brilliantly assured piano writing.

Originally the FANTASY-WALTZES should have been a suite of short characteristic

pieces in waltz rhythm but the work rapidly outgrew the composer's intentions.

Finally it became a big work full of contrasts, invention and colour, a true

kaleidoscope in waltz form. The TWELVE PRELUDES (1957) explore much stricter

material than the FANTASY-WALTZES and belong to the "serial" world of the

third and fourth symphonies and of the STRING TRIO. Each prelude has a clearly

defined character and the whole piece makes for a well-contrasted suite.

The fifth prelude was written in memory of Richard Farrel who was the dedicatee

and the first performer of the FANTASY-WALTZES. It is the emotionally weightier

one of the set.

The last record in this batch of Alwyn from CHANDOS is a most welcome release

and one for which I have been praying for many years. In the too brief period

in which I was privileged to know William Alwyn, I somewhat naively suggested

that he should make concert suites out of his best film scores. He then

regretfully told me that the scores were destroyed in the late fifties when

a fire destroyed Pinewood Studios thus causing the loss of many of his great

film scores as well as those of Walton and others. After Alwyn's death Mary

Alwyn set about sorting her husband's papers and found a number of sketches

of some film scores including ODD MAN OUT and a complete photocopy of the

score for THE FALLEN IDOL. The late Christopher Palmer prepared some suites

which are here recorded for the first time. Alwyn composed some 200 film

scores covering documentary films, fiction features and even three Disney

films.

Alwyn considered writing for films as serious a task as writing a symphony

or a string quartet. He used to do the orchestration himself which is why

his film music shares the same world as his serious works for the concert

hall. Alwyn was also happy in collaborating with noteworthy directors who

involved him from the start in the making of the film. Carol Reed was much

interested in the role of the music in his films.

His magnificent film ODD MAN OUT of 1946 is the only one the above-mentioned

films that I have seen. It made a deep impression and I found the music

wonderful. Hearing it afresh now confirms my feeling that the music for ODD

MAN OUT is really a great score, and quite simply a great piece of music.

The opening music rises to symphonic proportions while the long final scene

in which the wounded IRA gunner (James Mason) painfully makes his way to

the docks entirely rests on the music that has to support the action till

the end of the film. It is a long symphonic movement that opens in a mood

similar to that of the Passacaglia of the first violin concerto of Shostakovich.

It is a powerful March to the Abyss cut short by two gun shots and ending

with a short appeased coda. ODD MAN OUT and SHAKE HANDS WITH THE DEVIL (1959)

are probably among Alwyn's greatest scores and really transcend film music.

The score for THE HISTORY OF MR POLLY (1949) is of course somewhat lighter

but again it is superb full of fine touches such as the exhilarating Punting

Sequence which is a brisk and joyful Scherzo for woodwind. THE FALLEN IDOL

(1948) is another beautiful score and also belongs amongst his most successful.

It is full of invention and of masterly orchestral strokes such as the superb

Scherzo "Hide and Seek" of which the rather ghastly mood is enhanced by the

scoring for muted strings and muted brass. These three film scores are evident

examples of the importance that Alwyn attached to his music for films. They

are sizeable spans of music and each suite lasts some twenty minutes, that

of ODD MAN OUT lasting some twenty-six minutes.

This says a lot about the real musical quality of these scores which are

important milestones in Alwyn's large and varied output. The last item of

this fine release is the highly enjoyable "Calypso" from THE RAKE'S PROGRESS

(1945). Here Alwyn writes a very fine mood piece somewhat reminiscent of

Milhaud in his South-American mood. One could not have dreamed a finer conclusion

to this indispensable record which I unreservedly recommend. I am a bit short

of superlatives to praise the performances and the playing of the London

Symphony Orchestra conducted by Richard Hickox who again demonstrates his

deep sympathy with and feeling for Alwyn's music.

© Hubert CULOT

WILLIAM ALWYN Chamber Works

Sonata for Clarinet and Piano (1962)

Divertimento for Solo Flute (1939)

Crepuscule - Solo Harp (1955)

Sonata for Oboe & Piano (1934)

Sonata for Flute & Piano (1948)

Sonata Impromptu for Violin & Viola (1939)

Nicholas Daniel, oboe - Kate Hill, flute - Joy Farrall, clarinet Julius Drake,

piano - Ieuan Jones, harp - Leland Chen, violin Clare MacFarlane, viola

CHANDOS CHAN 9197

Alwyn's early chamber music was mainly written for colleagues and friends

with whom he used to play as a flautist. It is always superbly written for

the instruments and designed to exploit the instruments at their best. This

expertise was gained through numerous performances of the then modern music

(Ravel, Roussel and others). The first volume released by CHANDOS (CHAN 9152)

made this fairly clear and the second one under review certainly confirms

it.

The CLARINET SONATA written in 1962 for Thea King is a work belonging to

his most mature period. It is a comparatively short work though a tightly-knit

one laid-out in a single movement of considerable musical substance and packed

with energy. It opens with a brisk, nervous gesture immediately followed

by some more relaxed material. A very fine addition to the repertoire of

the clarinet. Much earlier is the DIVERTIMENTO FOR FLUTE written in 1939

and first performed in 1940 by Rene Le Roy at the ISCM festival in New York.

Expertly written for the instrument the piece stills shows the neo-classical

features that Alwyn was soon to abandon. As might be expected this virtuosic

piece exploits the possibilities of the flute to the full and makes serious

demands on the player. It earned its composer his first international success.

CREPUSCULE is a very short piece written for Sidonie Goossens. "The piece

is meant to suggest a cold, clear winter's night with frost snow" (Alwyn).

A delightful atmospheric piece. The OBOE SONATA of 1934 is by far the earliest

piece in this collection. The work was given at a concert of the New Music

Society and was then well received. It is in three movements: a lengthier

first movement followed by a choral-like Andantino. It ends with a livelier

finale capped by a more reflective Coda. The music is naturally more akin

to the British and (maybe more significantly still) French music of its period,

and it exhibits very little of Alwyn's fingerprints. Another worthwhile addition.

Surprisingly enough Alwyn wrote few large-scale works for his instrument.

The FLUTE SONATA of 1940 is actually very short though again of some substance.

Its one movement structure clearly falls into three sections and it again

ends with a short coda. The sonata still has some neo-classical characteristics

such as the fugue in the Allegro ritmico e feroce. The SONATA IMPROMPTU composed

in 1939 was written for Watson Forbes who played it with Frederick Grinke.

Though the piece seems to have enjoyed some performances in the 40s it has

remained virtually unheard since then. (For information's sake, this piece

is listed as SONATA QUASI FANTASIA in Poulton's "William Alwyn : A Catalogue

of his Music" [BRAVURA PUBLICATION 1985 - soon to be replaced by Poulton's

devastatingly comprehensive three volume Greenwood Press Dictionary of British

Composers].) A short prelude and fugue leads directly into a lengthier and

weightier theme and variations. The piece ends with a Finale alla Capriccio.

The sonata for violin and viola is an important addition for it unquestionably

is a big piece superbly written for the instruments and full of beautiful

moments. It is by far the most important piece in this collection (i.e. besides

the DIVERTIMENTO and the CLARINET SONATA).

The performances are all assured, confident and committed; and this beautiful

record lifts the veil on a number of nearly forgotten Alwyn works that certainly

deserve to be heard again. This record is again a worthwhile addition to

Alwyn's discography and it again helps widen our appreciation of Alwyn's

large and varied chamber output.

Hubert CULOT

|