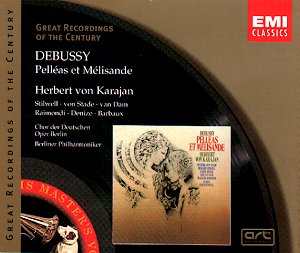

Pelléas.............................Richard Stilwell

Mélisande.........................Frederica van Stade

Golaud........................... José van Dam

Arkel.............................. Ruggero Raimondi

Geneviève.........................Nadine Denize

Yniold........................... ..Christine Barbaux

Choir of the German Opera, Berlin

The Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Herbert von Karajan

Background and Critical Acclaim

What a perfect medium Maeterlinck's play is for Debussy's moody impressionistic

music - heavy with symbolism, enigmatic and imprecise leaving much to the

imagination. As Debussy admitted, in the context of his opera, silence is

used as a means of expression -leaving the audience's imagination to fill

in the detail. This opera has no set pieces, no grand arias. It is all

atmosphere, all mood. The orchestra is the main protagonist with the singers

delivering their parts in a form of heightened and shaded speech almost as

though they were declaiming poetry. It was Debussy's exquisite achievement

in blending these vocal lines so superbly into his overall music tapestry.

Following the example of Wagner, Debussy uses a system of leitmotifs and

thematic transformations. Although Debussy tried to distance himself from

what he called "the ghost of old Klingsor", nevertheless the influence of

Tristan und Isolde and Parsifal on Pelléas et

Mélisande is very apparent as Karajan eloquently proves in this

recording.

The opera gestated, and was drafted and revised over a period of nine years

from 1893 during a period of great turbulence and emotional upheaval in the

composer's life. It was premiered under the baton of André Messager

in April 1902. Many were baffled by it and many unkind words were spoken

about it. Yet it was a considerable success; so much so that Debussy discouraged

too long a run for fear of crudities entering the production and of singers

improvising and ruining the work

Karajan conducted the opera in Rome in 1954 upsetting Toscanini because Karajan

insisted that it should be sung in the original French. In 1962 he had conducted

a legendary production at the Vienna State Opera. Commenting on this performance,

Joseph Wechsberg writing in Opera magazine said, "For the first

time in my experience, I was shaken by the power of Debussy's music; previously

I had only been moved by its beauty. This is a lyrical and a dramatic

interpretation and when the inexorable climax comes towards the end one sits

spellbound. Karajan opens the delicate texture of the score, lovingly displaying

its beauty ...and always painting, painting with music." These eloquent

comments equally apply to this recording as do the words of Neville Cardus,

describing the same Vienna production, which I reproduce here in full -

"Pelléas et Mélisande is a drama of the inner, the really

"real" world, a drama of implications, of psychological conflicts too secret

to concentrate into the obvious attitudes of life, exhibitory and active...Arkel

is old age poignantly particularised. The music by which Debussy gives him

grief and wisdom is bowed in its sombre-moving phrases and harmonies, so

pathetically in contrast to the golden throated lyricism of Pelléas;

the innocent youngness - but older in herself than she knows - of

Mélisande; and the simple manliness of Golaud, that unfortunate horseman.

All these people are pulsating themselves, but we see them from a distance:

they move in a permanent timeless dimension. It is ourselves, watching and

overhearing from our clock-measured, active, merely phenomenal world, who

are unreal. Debussy does not describe, he evokes. His orchestra, unlike Wagner's

does not point. It covers everything, a veiled, unheard, yet heard, presence

- omnipresent. I can think of no better compliment to Karajan...and the singers

than to say that all these intrinsic qualities of the work were brought home."

Karajan made this acclaimed recording in 1978 when he was 71 years old, body

infirm but mind and spirit as sharp as ever. He had begun to take on Arkel-like

qualities of wisdom and resignation which manifest themselves in this recording.

Karajan's attention to detail was remembered by Frederica von Stade who recalled

that the maestro rehearsed the orchestra over and over again until they achieved

the effect he wanted in the Act IV love scene immediately after Pelléas's

declaration, "Je t'aime" and Mélisande's reply "Je t'aime aussi".

On Pelléas's line, "On a brisé la glace avec des fers rougis!"

("The ice has been broken with red hot irons!") there is an amazing sound

high in the violins an effect that took great effort to get absolutely right.

The Review

The opera opens with the meeting of widower Golaud, already greying, with

the younger Mélisande in the forest. He is searching for an animal

he had wounded. She is there in mysterious circumstances, never explained,

gazing into a pool where there lies a lost crown. She does not appear to

want it when Golaud offers to retrieve it. Debussy's music paints the scene

- the forest mysterious, dense and dark, and sensual too, hinting at hidden

passions both present as Golaud falls under Mélisande's quiet spell

and immediate past tragedies and losses(?) in Mélisande's life. Somewhat

reluctantly she is persuaded to follow Golaud out of the forest. Symbolically

he admits, as the scene closes, that he is as lost as she is. The following

interlude carries forward this shadowy, mysterious mood before the textures

lighten somewhat to admit pastoral sounds of birdsong and creatures of the

forest. Frederica Von Stade conveys a distant purity and vulnerable innocence

in the part of Mélisande and José van Dam is a sympathetic

(at this stage in the story) and strong Golaud.

In scene II of Act I the action moves to the castle where Geneviève,

mother to Golaud and Pelléas , is reading to the old half-blind King

Arkel a letter Golaud has written to Pelléas. Golaud tells him that

Mélisande after six month's marriage, remains as mysterious to him,

as when he first met her. He hopes that Pelléas will persuade the

King to receive Mélisande. He goes on to say that he will look for

a light on the turret of the castle from his ship and come ashore if he receives

the signal but sail onwards if it is refused. A resigned Arkel (sung with

quiet dignity by Ruggero Raimondi) accepts the situation although he had

hoped that Golaud might marry Princess Ursula helping to heal rifts among

rival Princes. Pelléas, no doubt having some premonition, wants to

go to the aid of a dying friend but Arkel persuades him to remain and meet

his brother and his new wife. The rest of Act I concerns the arrival of Golaud

and Mélisande at night. Mélisande does not like the look of

the dark gloomy forests that press about the castle and is saddened that

Pelléas tells her he, himself, might have to leave. Debussy's music

vividly evokes the darkness and mists over velvet black water as the ship

that has brought Mélisande prepares to leave harbour - and the sense

of the irrevocability of destiny now set in train is palpable.

Act II opens with Pelléas and Mélisande beside the Fountain

of the Blind. Irresponsibly, and significantly, she tosses her wedding ring

in the air and lets(?) it fall into the deep waters. "I threw it too high

towards the sun," she claims and Pelléas tells her she must own up

to the truth to Golaud. Meanwhile, far away and at the precise moment the

ring is lost, Golaud's horse rears up; the music tightens and becomes darkly

foreboding. Back at the castle, Golaud is angry when he learns of the loss

of the ring and demands that Mélissande go and find it immediately.

She lies to him saying the ring was lost in a cave and of course Pelléas

and Mélisande's search there, in growing darkness, is pointless. Debussy's

tone painting of the darkening sea, and the lights and shadows playing on

the roof of the cave is again beautifully impressive.

Act III commences with the famous scene where Mélisande hangs her

hair out of the castle tower window and Pelléas immerses himself in

it and declares that it loves him more than she does. Debussy points up the

metaphor here likening Pelléas's immersion in the waves of

Mélisande's hair to drowning in the waves of the sea. (In turn, this

'sea' as it so often does in music, symbolises passion and a sense of drowning

in love.) Richard Stilwell, as Pelléas, conveys both the surface innocence

of his child-like game, and his hardly-recognised underlying passion.

Mélisande is clearly frightened and Golaud happening upon the episode

begins to suspect something is going on. This is manifested when he shows

Pelléas the vaults below the castle, the music symbolically suggesting

dank, still black waters but lightening as the two men ascend the stairs

into the fresh air and the scent of roses. But Golaud advises Pelléas

to avoid his wife. This proves to be impossible and in the next scene, outside

the castle, Golaud questions his little son about the behaviour of Pelléas

and Mélisande together. He cannot be assured that the pair are innocent

and makes the poor little boy spy on the hapless pair. Debussy's music becomes

increasingly tense and dramatic as Golaud's suspicions cloud his judgement

and he is filled with jealous anger and frustration. Van Dam cleverly portrays

Golaud's rapidly increasing paranoia.

Act IV Pelléas is persuaded by Arkel to leave but before he goes,

he requests a final meeting with Mélisande. She is distraught but

agrees. Arkel in a mood of optimism persuades Mélisande and himself

that things will improve and begs a kiss of affection. (Raimondi is particularly

fine and vulnerably human in this aria). But Golaud enters and in a fit of

jealous anger questions, berates and beats his wife. The music clearly shows

that he is now completely deranged and out of control. Later Pelléas

and Mélisande meet to say their farewells, but declare their love

and embrace, their clinging shadows reaching across open ground to where

Golaud is hiding amongst the trees. He emerges and slays Pelléas.

This whole scene is one of the highpoints, if not the highpoint of the whole

opera. It is a potent mixture of ardent romantic music and terror. Yet the

music tells us so much more; we can sense Mélisande's own sense of

tragic inevitablility as she seemingly surrenders, without resistance to

fate.

Act V and Mélisande lies mortally ill after giving birth to a baby

girl. She is cared for by an understanding Arkel. Golaud also present is

grief-striken and full of remorse yet he is obsessed to know the truth of

the relationship between Pelléas and his wife. In his brutality to

know what he feels is the truth, he pushes Mélisande over into death.

The opera ends in great beauty as the suffering soul of Mélisande

departs.

This is a wonderful production. Pelléas et Mélisande is not

an easy work. For those unfamiliar with this opera, I would caution that

it requires patience and repeated hearings to fully appreciate all its riches

but such commitment is well worthwhile.

Reviewer

Ian Lace