Voices of the Past

By Brian Wilson

Regular readers may recall that my round-ups used to include frequent

reviews of recordings from Beulah and Naxos Archives, made from 78s and LPs

up to the European copyright date of 1962. In addition to download-only

material from those and other sources, it is still possible to obtain

recordings deleted on CD, not just as downloads, but, in some cases, as

specially licensed CDRs from Presto, while Chandos and Hyperion also offer

special CDRs (and downloads) of their deleted CDs.

Index:

BARBER

Essence of – Beulah

BRAHMS

Symphony No.3 – Schuricht (rec. live 1963) – Legendary Archives

BRUCKNER

Symphony No.3; Richard STRAUSS Tod und Verklärung

– Knappertsbsuch (rec live 1964) – Legendary Archives

GAY

Beggar’s Opera – Sargent – Beulah

GOMBERT

Music from the Court of Charles V – Sony/Presto

HANDEL

Arias – Ferrier, McKellar – Beulah

JONES

Symphonies Nos. 3 and 5 – Thomson – Lyrita

MAHLER

Symphony No.5 – Konwitschny (live 1960) – Legendary Archives

- Symphony No.7 – Kubelík (live 1960) – Legendary Archives

PROKOFIEV

Cinderella

– Pletnev – DG/Presto

RODRIGO

Concierto de Aranjuez

– Yepes/Argenta (with solo guitar music – John Williams) – Beulah

SHOSTAKOVICH

Symphony No. 5 – Ormandy (live 1958) – Legendary Archives

- Symphony No.8 – Haitink – Decca/Presto CD; Silvestri (live 1958) –

Legendary Archives.

- Symphony No.12 – Ivanov (live 1961) – Legendary Archives

SIMPSON

Symphonies Nos. 5 and 6 – Davis, Groves – Lyrita

VAUGHAN WILLIAMS

– Tallis Fantasia; Symphony No.5 – Bush (1953, 1955) – Legendary Archives

VAUGHAN WILLIAMS

– Tallis Fantasia; Symphony No.5 – Bush (1953, 1955) – Legendary Archives

Adagio

– 10 Slow Movements – Beulah

Brendel

– Early Recordings (vols. 1-3) – Beulah

Elijah Rock

– Mahalia Jackson – Beulah

Organ of the Tower Ballroom, Blackpool – Dixon - Beulah

***

Beulah

I have quite a bit of catching up to do since my last survey of Beulah

reissues in November 2020.

I imagine that more people will have heard of at least some of the music

from the Bertolt Brecht/Kurt Weil Dreigroschenoper, or Threepenny

Opera (‘Mack the Knife’ ring a bell?) than of its model, John GAY’s Beggar’s Opera, put together in 1728

with music by Johann Christoph Pepusch, largely arranged

from ballad songs and snatches. It doesn’t get too many outings, though, by

coincidence, I see that a DVD/blu-ray recording, featuring Les Arts

Florissants and William Christie, has just been released on the Opus Arte

label. I haven’t seen that, so my benchmark remains the 2-CD 1991 Hyperion

recording directed by Jeremy Barlow (CDA66591/2 – Archive Service or

download with pdf booklet from

hyperion-records.co.uk).

I imagine that more people will have heard of at least some of the music

from the Bertolt Brecht/Kurt Weil Dreigroschenoper, or Threepenny

Opera (‘Mack the Knife’ ring a bell?) than of its model, John GAY’s Beggar’s Opera, put together in 1728

with music by Johann Christoph Pepusch, largely arranged

from ballad songs and snatches. It doesn’t get too many outings, though, by

coincidence, I see that a DVD/blu-ray recording, featuring Les Arts

Florissants and William Christie, has just been released on the Opus Arte

label. I haven’t seen that, so my benchmark remains the 2-CD 1991 Hyperion

recording directed by Jeremy Barlow (CDA66591/2 – Archive Service or

download with pdf booklet from

hyperion-records.co.uk).

From an earlier period comes the Beulah reissue of the 1955 recording

conducted by Sir Malcolm Sargent, with the Pro Arte Chorus and Orchestra

and an almost predictable cast for the time: Elsie Morison, Constance

Shacklock, Anna Pollak, Monica Sinclair, Alexander Young, John Cameron,

Owen Brannigan and Ian Wallace (10PD13 [1:27:20]). The

Hogarth painting on the cover, predictably, features on both recordings,

but they part company in that Sargent uses the Austin edition while Barlow

returns to the earthier original, with the Bowdlerised bits un-Bowdlerised.

Unlike the Italian-texted operas of Handel, the Beggar’s Opera

relies on spoken text in the vernacular, much of it replete with satire and

humour that meant a great deal to the audiences of the time, but now

requires footnotes, like Pope’s Dunciad, which makes it less

immediately accessible to a modern audience. (I nearly said ‘boring’, but

that would have given away the reason why my C18 paper earned me the lowest

mark in finals.) We can listen to and enjoy Judas Maccabæus

without knowing that the conquering hero was inspired by the Duke of

Cumberland and his role in putting down the 1745, but to hear the Beggar’s Opera in its original form is as if listeners 300 years

hence were to listen to an opera while scratching their heads over references

to Donald Trump, QAnon, Boris Johnson and the pandemic.

So, the Hyperion is more authentic and better recorded, in stereo, contains

an hour more of the work, and comes with a pdf booklet containing the text,

but I suspect that most modern listeners would prefer the much livelier

older Sargent recording, as well transferred as it is by Beulah. Among the

virtues of the older recording are the occasional interventions, as if from

the original audience. The Hyperion download costs £16.99 (link above), the

Beulah £11.99 in lossless sound from

Qobuz

or £7.99 in mp3 from

AmazonUK.

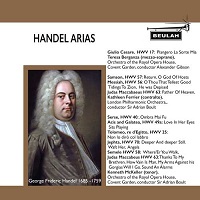

There’s a good deal of Kathleen Ferrier on an album of HANDEL Arias (1PS89 [69:48]): Samson – ‘Return, O God of Hosts’; Messiah – ‘O thou that

tellest’; ‘He was despised’; Judas Maccabæus – ‘Father of Heaven’,

with the London Philharmonic Orchestra and Sir Adrian Boult. This is plain

singing, without any of the modern attempts to reproduce the ornamentation

of Handel’s day, the Messiah just as printed in the old Ebenezer

Prout edition. I don’t normally warm to Ferrier’s voice, for reasons which

I’ve gone into many times, but this was one of the recordings where the

engineers caught her at her best, so popular on LP that Decca later

re-recorded the accompaniment in stereo, but this (1952, mono) original is

preferable. Her work as a telephonist would already have ironed the

Lancashire vowels out of her voice, but there’s still a hint of her native

Walton-le-Dale in ‘behold your God’.

There’s a good deal of Kathleen Ferrier on an album of HANDEL Arias (1PS89 [69:48]): Samson – ‘Return, O God of Hosts’; Messiah – ‘O thou that

tellest’; ‘He was despised’; Judas Maccabæus – ‘Father of Heaven’,

with the London Philharmonic Orchestra and Sir Adrian Boult. This is plain

singing, without any of the modern attempts to reproduce the ornamentation

of Handel’s day, the Messiah just as printed in the old Ebenezer

Prout edition. I don’t normally warm to Ferrier’s voice, for reasons which

I’ve gone into many times, but this was one of the recordings where the

engineers caught her at her best, so popular on LP that Decca later

re-recorded the accompaniment in stereo, but this (1952, mono) original is

preferable. Her work as a telephonist would already have ironed the

Lancashire vowels out of her voice, but there’s still a hint of her native

Walton-le-Dale in ‘behold your God’.

For all that I find this a better representation of Ferrier, the opening

track, the aria from Giulio Cesare – ‘Piangero la sorte mia’, sung

by Teresa Berganza (rec. c.1960, stereo), is more impressive.

The rest of the recital concentrates on Kenneth McKellar, with Boult again

conducting: ‘Ombra mai fu’ (Serse); ‘Love in her eyes sits

playing’ (Acis and Galatea); ‘Did you not hear my lady’ (a modern

confection after music from Ptolemy); ‘Where’er you walk’ (Semele), three extracts from Judas Maccabæus and three

from Jephtha. A fine voice, not helped by its employment in the

more popular

repertoire with which McKellar was associated, which perhaps

explains some of the occasional strain on the longer-held top notes. These

recordings date from 1959 or 1960 and are in decent stereo. Lossless sound

from

Qobuz.

repertoire with which McKellar was associated, which perhaps

explains some of the occasional strain on the longer-held top notes. These

recordings date from 1959 or 1960 and are in decent stereo. Lossless sound

from

Qobuz.

Reginald Dixon at the Wurlitzer Organ of Tower Ballroom Blackpool

will bring back many memories for those who, like me as a child, regarded a

trip to Blackpool as a real treat, and a visit to the people’s palace of

the Tower Ballroom to see the mighty organ rise from below the floor an

absolute delight. Later, I came to prefer the more genteel Lytham St Anne’s

with its second-hand bookshops, but this Beulah recording of popular

classics and middle-of-the-road music made between 1935 and 1961, is real

trip down memory lane, which I seem to have missed when it was released in

December 2019.

(1PS55, mp3 from

AmazonUK; lossless sound from

Qobuz).

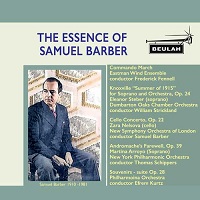

The Essence of Samuel BARBER

on 1PS87 [75:29] – mp3 from

AmazonUK; lossless sound from

Qobuz

– contains some familiar music and some unfamiliar. The short opening Commando March [3:10] comes from the Eastman Wind Ensemble

and Frederick Fennell, whose recordings are to be found on several Beulah

reissues.

The Essence of Samuel BARBER

on 1PS87 [75:29] – mp3 from

AmazonUK; lossless sound from

Qobuz

– contains some familiar music and some unfamiliar. The short opening Commando March [3:10] comes from the Eastman Wind Ensemble

and Frederick Fennell, whose recordings are to be found on several Beulah

reissues.

Knoxville – Summer of 1915

[13:59] is much more familiar, though I don’t recall hearing this recording

from Eleanor Steber (soprano), the Dumbarton Oaks Orchestra and William

Strickland before. This beautiful 1947 evocation of small-town life before

the US entered WWI was commissioned by Steber, and this recording, from US

Columbia, apparently dates from 1950 – if so, it has come up extremely well

in this transfer. There are more recent performances with more beautiful

solo singing, notably from Dawn Upshaw, and in better sound, but this

performance by the soprano who commissioned the work is special. I don’t

think it was issued in the UK until it appeared on a now defunct CBS

Masterworks Portrait CD in 1991.

The Cello Concerto (1946) – Zara Nelsova (cello), New

Symphony Orchestra of London conducted by the composer [27:25] – is also

fairly familiar Barber territory, as is this recording, which also dates

from 1950, this time for Decca and released on a 10” LP. With a soloist who

was already associated with the work, the composer conducting, and a good

transfer of the recording, this is the highlight of the reissue. As

released on Ace of Clubs in 1966, with Symphony No.2, this was my

introduction to the work, even at a time when I was turning my nose up at

mono reissues; Decca were already reissuing some of their prime stereo

recordings on Ace of Diamonds by then.

The album is rounded off with a powerful performance of Andromache’s Farewell, Op.39 [12:09] – Martina Arroyo

(soprano), New York Philharmonic Orchestra and Thomas Schippers (1963, but

not released in the UK at the time, perhaps a little too much like film

music) – and the least familiar item (to me) the Souvenirs Suite, Op.28 [18:44] (Philharmonia

Orchestra/Efrem Kurtz). Like Knoxville, the original Souvenirs ballet inhabits a pre-WWI world, this time in grand

society. There is no other current generally available recording, so this

reissue of one side of a 1956 HMV 10” LP is welcome, though I can’t claim

that this is music of the same quality as the two central works; it’s a bit

like Ravel’s la Valse without the irony. Though mostly of somewhat

venerable origin, these transfers really are worth purchasing from

Qobuz

in lossless sound, though they are also available from

AmazonUK

in mp3: both cost the same (£7.99).

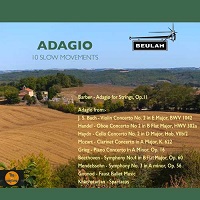

I know there is a ready market for snippet recordings; much as I would like

to think them a stepping stone to full symphonies, concertos or operas,

that’s as far as many are prepared to go. Designed to appeal to that market

is Adagio: 10 slow movements on 1PS90 [72:41]. Only the opening Samuel BARBER Adagio [7:44] was composed as a

stand-alone item. The cover doesn’t specify the provenance of any of these

recordings, but this is the idiomatic recording made by the Philadelphia

Orchestra and Eugene Ormandy – the information is in the codec if your

player can display it. (The free MusicBee programme can.)

I know there is a ready market for snippet recordings; much as I would like

to think them a stepping stone to full symphonies, concertos or operas,

that’s as far as many are prepared to go. Designed to appeal to that market

is Adagio: 10 slow movements on 1PS90 [72:41]. Only the opening Samuel BARBER Adagio [7:44] was composed as a

stand-alone item. The cover doesn’t specify the provenance of any of these

recordings, but this is the idiomatic recording made by the Philadelphia

Orchestra and Eugene Ormandy – the information is in the codec if your

player can display it. (The free MusicBee programme can.)

The closing

Aram KHACHATURIAN Adagio of Spartacus and Phrygia

[9:07], from the Spartacus ballet, also developed a life of its

own when it was used as the theme music for a TV programme about a shipping

family, The Onedin Line. The music actually has nothing to do with

a ship under full sail, but it seemed to fit perfectly, in this recording

made by the composer with the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra, still

available on the MVE label, download only, and short value with just 23

minutes from the ballet. Better to choose the Beulah.

The slow movement of the GRIEG Piano Concerto [6:00] in

one of my favourite recordings, from Clifford Curzon, the LSO and Øivind

Fjeldstad (1959), is another highlight of the collection, but it also

serves to point the listener to their complete recording, with the Schumann

Piano Concerto and Franck Symphonic Variations (Decca 4336282) or on a

Presto special CD

with Peer Gynt Suites (4485992). And who could fail to enjoy Sir

Thomas Beecham’s special magic with the Adagio from the Faust ballet music on the next track [4:16]?

Another old favourite, Maurice Gendron and Pablo Casals in the slow

movement of the HAYDN Cello Concerto in D, now known as

No.2 since the discovery of the concerto in C, also points to the complete

recording on another Beulah release, Great Cello Concertos. mp3

from

AmazonUK;

lossless sound from

Qobuz

Among the recent highlights from this label are three recordings made by

the young Alfred Brendel. What they lack in maturity and recording quality,

they more than make up for in sheer vitality:

1PS86

contains BEETHOVEN Fantasy in g minor, LISZT Piano Concertos Nos. 1 and 2 (with Vienna Pro

Musica/Michael Gielen) and MOZART Quintet for piano and

winds, K452 (with Hungarian Wind Quintet), rec. 1957-62. Download from

AmazonUK

(mp3) or

Qobuz

(lossless).

1PS86

contains BEETHOVEN Fantasy in g minor, LISZT Piano Concertos Nos. 1 and 2 (with Vienna Pro

Musica/Michael Gielen) and MOZART Quintet for piano and

winds, K452 (with Hungarian Wind Quintet), rec. 1957-62. Download from

AmazonUK

(mp3) or

Qobuz

(lossless).

We have just been reminded of the power of a young pianist’s Liszt in a

recital by Benjamin Grosvenor which includes the Piano Sonata (Decca). Ian

Julier has given that a Recommended accolade (pending), and I’m very happy

to concur with his very high opinion, but I’m equally happy to agree with

another new recruit to our team, David McDade, who thought these Liszt

concertos superb and the Mozart formidable –

review.

And, though I’ve mentioned the recording quality of the Vox recordings,

the sound has come up very well in this Beulah transfer.

2PS86: This is less familiar Brendel territory – MUSSORGSKY

Pictures from an Exhibition, STRAVINSKY Three Movements

from Petrushka, BALAKIREV Islamey andLISZT Harmonies poétiques et réligieuses: Invocation and Pensée des Morts, all recorded in 1955.

Download from

AmazonUK

(mp3) or

Qobuz

(lossless).

2PS86: This is less familiar Brendel territory – MUSSORGSKY

Pictures from an Exhibition, STRAVINSKY Three Movements

from Petrushka, BALAKIREV Islamey andLISZT Harmonies poétiques et réligieuses: Invocation and Pensée des Morts, all recorded in 1955.

Download from

AmazonUK

(mp3) or

Qobuz

(lossless).

Like most listeners, I find the Mussorgsky in the original piano version

something of a let-down after the Ravel and other orchestrations, but

Brendel does his best to add colour to the playing, both here and in the

Stravinsky, where orchestral music is re-imagined for the piano. Once

again, my colleague David McDade puts his finger on the matter – review

pending – by noting that Brendel looks carefully at each piece and

penetrates its meaning. Islamey is more of a show piece, and

doesn’t bring out the best in Brendel, but the Liszt finds him at home

again. These are older than the recordings on Volume 1 and, inevitably,

sound a little dry, but the transfer has, again, been judiciously made.

3PS86: BEETHOVEN Piano Concerto No.5 in E-flat, Op.73,

‘Emperor’ (rec. 1961, with Vienna Pro Musica and Zubin Mehta),LISZT Harmonies No.10 Cantique, and MOZART Concerto No.10 for two pianos and orchestra, K365

(with Walter Klien, VSOO and Paul Angerer). Download from

AmazonUK

(mp3) or

Qobuz

(lossless).

3PS86: BEETHOVEN Piano Concerto No.5 in E-flat, Op.73,

‘Emperor’ (rec. 1961, with Vienna Pro Musica and Zubin Mehta),LISZT Harmonies No.10 Cantique, and MOZART Concerto No.10 for two pianos and orchestra, K365

(with Walter Klien, VSOO and Paul Angerer). Download from

AmazonUK

(mp3) or

Qobuz

(lossless).

This recording of the Emperor has been through several transmogrifications since it

was first released on Vox STGBY512050. The ever-reliable Trevor Harvey

deemed the (1968) Turnabout reissue the work of ‘a very fine pianist who is

also intelligent to a high degree’. I’m not about to disagree with that,

except to note that the recording is a little on the dry side.

Brendel and Klien between them recorded several of the Mozart Piano

Concertos for Vox, so it’s appropriate that they paired up for K365.

Another of the reliable old reviewers, Jeremy Noble, dubbed this recording

‘astonishing and delightful … music making’. (It’s a sad indication of my

age that I remember reading the original review in 1961.) Once again, I’m

not likely to disagree with that summary. I praised the Beulah reissue of

Klien’s Mozart Piano Concerto No.14 when it was released separately in 2013

–

review

– and it’s equally worth having on Great Piano Concertos (with

Beethoven No.4, Backhaus, and Chopin No.2, Askenase – download or stream

from

Qobuz). Though Brendel received better recording quality when he was taken up by

Vanguard – see my

review

of Mozart Piano Concertos Nos. 9 and 14 – the Vox recording of K365 is

more than tolerable in this transfer.

An anthology entitled Classical Guitar (1PS88 [71:57]) just had to include the RODRIGO Concierto de Aranjuez, here offered in

one of the classic recordings, by Narciso Yepes, Orquesta Nacional de

España and Ataulfo Argenta (DG, stereo, 1957). That’s a recording which has

stood the test of time well – it’s still one of my versions of choice. Here

it sits well in the company of solo guitar music recorded by John Williams

in 1958: Albeniz, Ponce, Villa-Lobos, Sor, Segovia, Granados and

others. It’s also available on a budget Alto CD, ALC1379, with Rodrigo’s Fantasia para un Gentilhombre (Yepes again, with Frühbeck de

Burgos) and the Concierto serenata for harp and orchestra

(Zabaleta and Märzendorfer). This recording of Aranjuez has also

appeared on an earlier Beulah release, Guitar Concerto –

DL News 2014/2.

Choose the coupling according to your preference. Download from

AmazonUK

(mp3) or

Qobuz

(lossless).

An anthology entitled Classical Guitar (1PS88 [71:57]) just had to include the RODRIGO Concierto de Aranjuez, here offered in

one of the classic recordings, by Narciso Yepes, Orquesta Nacional de

España and Ataulfo Argenta (DG, stereo, 1957). That’s a recording which has

stood the test of time well – it’s still one of my versions of choice. Here

it sits well in the company of solo guitar music recorded by John Williams

in 1958: Albeniz, Ponce, Villa-Lobos, Sor, Segovia, Granados and

others. It’s also available on a budget Alto CD, ALC1379, with Rodrigo’s Fantasia para un Gentilhombre (Yepes again, with Frühbeck de

Burgos) and the Concierto serenata for harp and orchestra

(Zabaleta and Märzendorfer). This recording of Aranjuez has also

appeared on an earlier Beulah release, Guitar Concerto –

DL News 2014/2.

Choose the coupling according to your preference. Download from

AmazonUK

(mp3) or

Qobuz

(lossless).

One of Beulah’s specialities, military music, is represented here only by

the opening work in the Barber anthology, but another speciality, jazz, is

here in force in the form of 1PS92: Mahalia Jackson – Elijah Rock. As well as the title

work, the collection includes

He’s got the whole World in His Hands, When the Saints go marching in

(even livelier than Louis Armstrong), What a Friend we have in Jesus, Amazing Grace and Joshua fit the Battle of Jericho. Recorded between 1937 and 1959,

mostly live, the sound is inevitably variable, but the vivid Beulah

transfers make it all eminently listenable.

One of Beulah’s specialities, military music, is represented here only by

the opening work in the Barber anthology, but another speciality, jazz, is

here in force in the form of 1PS92: Mahalia Jackson – Elijah Rock. As well as the title

work, the collection includes

He’s got the whole World in His Hands, When the Saints go marching in

(even livelier than Louis Armstrong), What a Friend we have in Jesus, Amazing Grace and Joshua fit the Battle of Jericho. Recorded between 1937 and 1959,

mostly live, the sound is inevitably variable, but the vivid Beulah

transfers make it all eminently listenable.

My next project is an article on recordings for Passiontide and Easter, new

releases for 2021 and older favourites, including a new version for Alpha

of Handel’s Brockes Passion. The spiritual power of this Mahaliah

Jackson collection could easily merit a place in that collection. It wasn’t

yet available at the time of reviewing it; watch out for its appearance on

the Beulah webpage, and choose the Qobuz lossless download for preference.

***

Lyrita

For some time, in addition to their new recordings and

very valuable reissues from the LP

age, a treasure trove mainly of British music, Lyrita have been bringing us

excellent transfers from radio broadcasts made by their founder, Richard

Itter, and other broadcast recordings by arrangement with the BBC. Two

recent additions to those off-air refurbishments are especially well worth

getting to know, on CD or as downloads.

Daniel

JONES (1922-1993) Symphony No.3

(1951), rec. 26 January 1990 [28:29] and Symphony No.5

(1958), rec. 9 February 1990 [39:33]: BBC Welsh Symphony Orchestra/Bryden

Thomson, ADD/stereo. LYRITA SRCD.390 [68:03]. Reviewed as

downloaded from lossless press preview. CD from

Presto

or

Amazon UK.

Daniel

JONES (1922-1993) Symphony No.3

(1951), rec. 26 January 1990 [28:29] and Symphony No.5

(1958), rec. 9 February 1990 [39:33]: BBC Welsh Symphony Orchestra/Bryden

Thomson, ADD/stereo. LYRITA SRCD.390 [68:03]. Reviewed as

downloaded from lossless press preview. CD from

Presto

or

Amazon UK.

I closed my

review

of SRCD.364 – Symphonies Nos. 2 and 11 – with the hope that there was more

in the pipeline. Here it is, and it’s very welcome: music immediate in

appeal, yet powerful and genuinely symphonic in scope. Lyrita already had

recordings of some of the other symphonies: as well as the album referred

to above there’s Nos. 1 and 10, another BBC recording, on SRCD.358, Nos. 4,

7 and 8 on SRCD.329, and 6 and 9 on SRCD.326.

Robert SIMPSON (1921-1977) Symphony No.5

(1972): LSO/Andrew Davis, rec. 3 May 1973 [38:53] and Symphony No.6. (1977): LPO/Charles Groves, rec. 8 April

1980 [33:12], both ADD/stereo. LYRITA SRCD.389 [72:05]

Reviewed as downloaded from lossless press preview. CD from

AmazonUK.

Robert SIMPSON (1921-1977) Symphony No.5

(1972): LSO/Andrew Davis, rec. 3 May 1973 [38:53] and Symphony No.6. (1977): LPO/Charles Groves, rec. 8 April

1980 [33:12], both ADD/stereo. LYRITA SRCD.389 [72:05]

Reviewed as downloaded from lossless press preview. CD from

AmazonUK.

I’ve never quite come to terms with Robert Simpson, though I’ve listened to

and enjoyed the Hyperion series of his symphonies (CDS44191/7, 7 CDs or download, and separately as downloads) and chamber music, so I

was pleased that David McDade volunteered to review this release (review

pending). He was so impressed with No.5 that he has awarded Recommended

status, though he felt that No.6 had not received enough rehearsal time.

So, a challenge to the Hyperion No.5 (Vernon Handley with the RPO), though

Handley, with the RLPO, reigns supreme in No.6.

***

Presto CDR

From modest beginnings, Presto’s range of CDRs, licensed from the major

manufacturers, has grown to be considerable. Although most of the albums

are also available as downloads or for streaming, which is how I have

reviewed them, I know that many music lovers like to have the physical CD

with its booklet, the latter sadly all too often missing from the download.

You’ll find reviews of many of these Presto specials on our main review

pages, but I wanted to draw attention to the series and pick out a few here

that we seem to have missed.

I haven’t reviewed many of these Presto CDRs in physical form, but I did

very much appreciate the reissue of a Sony recording of the music of GOMBERT – Music from the Court of Charles V (SK48249 –

review). As with many of these Presto reissues, the inclusion of the booklet,

with texts and translations, identical to the original, and absent from any

download that I could find, is especially valuable.

I haven’t reviewed many of these Presto CDRs in physical form, but I did

very much appreciate the reissue of a Sony recording of the music of GOMBERT – Music from the Court of Charles V (SK48249 –

review). As with many of these Presto reissues, the inclusion of the booklet,

with texts and translations, identical to the original, and absent from any

download that I could find, is especially valuable.

Sergei PROKOFIEV (1891-1953)

Summer Night: Suite from The Duenna, Op.123 [20:13]

Cinderella, Op.87 [1:56:49]

Russian National Orchestra/Mikhail Pletnev

rec. 13 April 1994, Great Hall, State Conservatory, Moscow. DDD

Presto CD or download

DEUTSCHE GRAMMOPHON 4762233

[2 CDs - 2:16:44]

A complete recording of Cinderella, as opposed to the suites, is rare, and

the Summer Night Suite almost as rare. Add the fact that Presto

have given us two CDs for their regular price of £12.75, when the lossless

download costs more than that, bear in mind that this is a ‘Rosette

Collection’ album, a 3-star Penguin Classics recommendation, and you are

looking at a genuine bargain. The only rival comes from Vladimir Ashkenazy

with the Cleveland Orchestra (1983) on a Double Decca, with Glazunov The Seasons, a slightly less expensive proposition on CD at around

£11.50 and significantly less expensive as a download for around £10

(4553492).

Even when it was at full price, the Pletnev had an edge on other

recordings. At the price of the Presto CD, it’s unbeatable – unless you

must have the Glazunov, which, I must admit, is music that I turn to often.

You could download that separately from the Double Decca for around £4.

Dmitri SHOSTAKOVICH (1906-1975)

Dmitri SHOSTAKOVICH (1906-1975)

Symphony No.8 in c minor, Op.65 (1943) [61:42]

Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra/Bernard Haitink

rec. 1982.

Presto CD or download

DECCA 4116162

[61:42]

I’ve written (below – Legendary Archives) about the great disappointment

that this symphony caused in 1943. The authorities, who had been hoping for

something optimistic as the war was beginning to turn, made the best of a

bad job and dubbed it a memorial for the victims of Stalingrad – it’s more

likely to be for the victims of Stalin himself, but you dare not even think

that in Russia in 1943.

This Haitink recording has been through several metamorphoses on CD; the

Presto CDR restores the catalogue number and cover of the first of them. At

one time it was a budget-price offering on the Eloquence label, and it’s

still available at mid-price on Decca Virtuoso, but that’s advertised as

out of stock at the UK distributors, and the lossless download, at £11.11,

is more expensive than the CD, leaving the Presto CD your best option. It’s

a safe option, too, with a fine performance from all concerned, and well

recorded, and I found myself preferring it to Ashkenazy in his complete

Shostakovich set –

review

– now download only. It’s just a little tame, however, by comparison with

Mravinsky on budget-price Alto and the live Silvestri recording from

Legendary Archives (details of both below).

I’ve mentioned some Presto Britten-conducts-Britten recordings in

my recent

overview of Decca and DG releases:

English Music for Strings:

English Music for Strings:

Henry PURCELL (1659-1695)

Ciacona in g minor, Z.730 (arr. Britten) [6:59]

Sir Edward ELGAR (1857-1934)

Introduction and Allegro for strings, Op.47 (1905)1 [14:09]

Benjamin BRITTEN (1913-1976)

Prelude & Fugue for 18 strings, Op.29 [9:12]

Simple Symphony, Op.4 [17:16]

Frederick DELIUS (1862-1934)

(orch. Eric Fenby) Two Aquarelles (1917.1932) [5:14]

Frank BRIDGE (1879-1941)

Christmas Dance ‘Sir Roger de Coverley’ [4:27]

Cecil Aronowitz (viola), Emanuel Hurwitz (violin), José Luis Garcia

(violin), Bernard Richards (cello)1

English Chamber Orchestra/Benjamin Britten

rec. May and December 1968, September 1971, Maltings, Snape. ADD

Reviewed as streamed in 16-bit lossless sound.

Presto CD

or download

DECCA 4761641

[57:19]

The Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra, Op.341 [16:34]

The Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra, Op.341 [16:34]

Peter Grimes

(1945): Four Sea Interludes and Passacaglia, Op.33a2 [23:21]

Soirées musicales

(after Rossini), Op.93 [9:34]

Matinées musicales

(after Rossini), Op.243 [13:15]

London Symphony Orchestra/Benjamin Britten1; Royal Opera House

Covent Garden/Benjamin Britten2; National Philharmonic

Orchestra/Richard Bonynge3

rec. May 1963, Kingsway Hall, London, ADD1; December 1958,

Walthamstow Assembly Hall, London, ADD2; March 1981, Kingsway

Hall London, DDD3

Presto CD

or download

DECCA 4256592

[62:44]

See the Decca and DG Article for details (link above).

***

Legendary Archives

The raison d’être of this label, which I have only just encountered, is

rather different. Most of the albums which they offer are not reissues of

commercial releases but previously unpublished live recordings. As with

Beulah, there are no booklets, only the information carried on the cover.

My review copies were in flac format, but at a low bit-rate, not much

higher than mp3, which is probably fair enough for recordings of this

provenance: no bit-rate, however high, can add what isn’t there.

Three very interesting recordings of Shostakovich are among the best of the

offerings.

LA003: SHOSTAKOVICH Symphony No.8: Constantin Silvestri

conducting the USSR State Symphony Orchestra live at the Moscow

Conservatory on 22 October 1958 [61:59]. ADD mono from

Legendary Archives. Very little is left of Silvestri conducting Shostakovich; apart from this

Legendary Archives download, I’ve been able to locate only one

download-only offering on the BnF label: Symphony No.5 with the VPO (1962),

which was not well received. The Vienna orchestra can’t have been too

familiar with Shostakovich at that time, but Silvestri conducting his

Eighth in Moscow with the USSR State Symphony must have been akin to

carrying coals to Newcastle.

LA003: SHOSTAKOVICH Symphony No.8: Constantin Silvestri

conducting the USSR State Symphony Orchestra live at the Moscow

Conservatory on 22 October 1958 [61:59]. ADD mono from

Legendary Archives. Very little is left of Silvestri conducting Shostakovich; apart from this

Legendary Archives download, I’ve been able to locate only one

download-only offering on the BnF label: Symphony No.5 with the VPO (1962),

which was not well received. The Vienna orchestra can’t have been too

familiar with Shostakovich at that time, but Silvestri conducting his

Eighth in Moscow with the USSR State Symphony must have been akin to

carrying coals to Newcastle.

It’s in mono, with a few coughs and splutters, and sounds a bit growly

below and thin on top, but that’s not inappropriate for the music’s often

bleak tone – this really was not the work that Stalin had been hoping to

raise spirits as the war was finally turning in the Allies’ favour. Hoping

that the Ninth would be celebratory – it wasn’t – the authorities made the

best of it by calling the Eighth the ‘Stalingrad’ Symphony.

Dan Morgan thought the Mravinsky recording of this symphony ‘a mandatory

purchase’ (Alto ALC1150 –

Spring 2017/2) but Shostakovich lovers should have this Silvestri recording, too. (See

above for Presto CD reissue of the Haitink recording).

LA004: SHOSTAKOVICH Symphony No.12

in d minor, Op.112, ‘The Year 1917’ [36:59]: the Moscow premiere broadcast

from Konstantin Ivanov with the USSR State Symphony Orchestra, recorded

live in the Moscow Conservatory on 15 October 1961, and never previously

released, is even more special, especially as it comes with a commentary on

the music by the composer, briefly and in Russian, of course. Recorded

off-air, with two short dropouts in the broadcast, it requires even more

tolerance than most of this series. It sounds as if the broadcast was in

AM, rather than FM; where many of these releases are shrill and a bit

papery, this is muddy at first, but it improves, and it’s worth

persevering. ADD mono from

Legendary Archives.

LA004: SHOSTAKOVICH Symphony No.12

in d minor, Op.112, ‘The Year 1917’ [36:59]: the Moscow premiere broadcast

from Konstantin Ivanov with the USSR State Symphony Orchestra, recorded

live in the Moscow Conservatory on 15 October 1961, and never previously

released, is even more special, especially as it comes with a commentary on

the music by the composer, briefly and in Russian, of course. Recorded

off-air, with two short dropouts in the broadcast, it requires even more

tolerance than most of this series. It sounds as if the broadcast was in

AM, rather than FM; where many of these releases are shrill and a bit

papery, this is muddy at first, but it improves, and it’s worth

persevering. ADD mono from

Legendary Archives.

The only other generally available recording of Ivanov’s Shostakovich comes

in the form of his account of the ‘Leningrad’ Symphony, also with the USSR

State Orchestra (Alto ALC1241, budget price, or Complete Symphonies:

Legendary Russian Composers ALC3143, 12 CDs, around £40). Rob Barnett

described Ivanov on another Shostakovich recording as ‘ringingly authentic’

–

review

– and this performance of No.12 must be regarded as definitive.

That complete set includes Rudolf Barshai’s highly-regarded WDR recording

of No.12. Ivanov outpaces him in three of the movements, making the

climaxes even more climactic, but he gives much more weight to the second

movement, unfortunately punctuated by the occasional cough, but it was a

live performance and the Moscow Autumn had set in. Even Mark Wigglesworth,

on a well-liked recording with the Netherlands Philharmonic, sounds a

little tame by comparison, though the SACD or 24-bit download is obviously

much more truthful (BIS-1563, with No.9 –

review).

I’ve never really subscribed to the idea that the Twelfth is the weakest of

the Shostakovich symphonies, especially having heard the Rozhdestvensky

recording with the USSSR Ministry of Culture Orchestra (1983), which used

to be available from Olympia (OCD200). I’m even less inclined to that

opinion after hearing this Russian recording.

LA033: Eugene Ormandy conducting the Philadelphia Orchestra at the Bordeaux

Festival on 17 May 1958 must have been quite an occasion. It’s an

interesting programme, too:BEETHOVEN Egmont Overture, Op.84, SHOSTAKOVICH Symphony No.5 in d minor, Op.47,Virgil Thomson Suite from Louisiana Story,STRAVINSKY Firebird Suite (1919 version) and BERLIOZ Hungarian March. [98:51] The sound is resolutely

mono; like most of these releases, it requires a deal of tolerance and, of

course, there are more recent recordings of Ormandy in much of this music –

the Shostakovich, for example, in a budget-price 3-CD set (Sony

19439704792: Symphonies 1, 4, 5 and 10, Cello Concerto No.1 and Polka from The Golden Age). Better still, Dutton have recently released

Ormandy’s Symphonies Nos. 5 and 15 and other music on SACD –

review

– but these live performances are special. ADD mono from

Legendary Archives.

LA033: Eugene Ormandy conducting the Philadelphia Orchestra at the Bordeaux

Festival on 17 May 1958 must have been quite an occasion. It’s an

interesting programme, too:BEETHOVEN Egmont Overture, Op.84, SHOSTAKOVICH Symphony No.5 in d minor, Op.47,Virgil Thomson Suite from Louisiana Story,STRAVINSKY Firebird Suite (1919 version) and BERLIOZ Hungarian March. [98:51] The sound is resolutely

mono; like most of these releases, it requires a deal of tolerance and, of

course, there are more recent recordings of Ormandy in much of this music –

the Shostakovich, for example, in a budget-price 3-CD set (Sony

19439704792: Symphonies 1, 4, 5 and 10, Cello Concerto No.1 and Polka from The Golden Age). Better still, Dutton have recently released

Ormandy’s Symphonies Nos. 5 and 15 and other music on SACD –

review

– but these live performances are special. ADD mono from

Legendary Archives.

[As I was completing this review, I learned that this recording is no

longer on offer. I do hope it will be possible to release it again in

future, so I’ve left the review in place to emphasise that hope.]

LA025: MAHLER Symphony No.7

in e minor, live from the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra and Rafael Kubelík

in the Musikverein, Vienna, on 19 and 20 November 1960. ADD/mono from

Legendary Archives.

[75:06] Apparently, this was the first time the VPO had performed this

symphony, now frequently to be heard in the concert hall or on record, for

almost 30 years, and only the fourth time it had been given by them. That’s

not to say that the orchestra was anti-Mahler: they had recorded Das Lied von der Erde with Bruno Walter as early as 1937 –

complete on seven 12” 78 rpm records, costing the princely sum of two

guineas (£2.10, but multiply that by at least 50 for today’s equivalent).

LA025: MAHLER Symphony No.7

in e minor, live from the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra and Rafael Kubelík

in the Musikverein, Vienna, on 19 and 20 November 1960. ADD/mono from

Legendary Archives.

[75:06] Apparently, this was the first time the VPO had performed this

symphony, now frequently to be heard in the concert hall or on record, for

almost 30 years, and only the fourth time it had been given by them. That’s

not to say that the orchestra was anti-Mahler: they had recorded Das Lied von der Erde with Bruno Walter as early as 1937 –

complete on seven 12” 78 rpm records, costing the princely sum of two

guineas (£2.10, but multiply that by at least 50 for today’s equivalent).

This recording is taken from the two performances that Kubelík gave on

subsequent days. Kubelík’s Mahler has always appealed to me – his recording

of the First Symphony is still my version of choice (DG Originals 4497352,

download only). His complete DG set of the Mahler symphonies remains

available on 4637382, 10 CDs.

The sound of the 1960 performance is dry and a little fragile, but

tolerable, and the performance brings the extra frisson of a live

performance. Good as the Bavarian Radio Orchestra is on the DG set, and

rusty though the VPO may have been in this symphony, there is something

special about their playing – if only the recording quality could convey it

more fully.

LA039

brings a recording of BRAHMS Symphony No.3 from Carl

Schuricht, very late in his career, conducting the Munich Philharmonic

Orchestra (live, Herkulessaal, Munich, May 19, 1963). There are a few

extant recordings of Schuricht’s Brahms, especially of Symphony No.2, but

the only other way to find him conducting the Third is, I believe, via the

complete SWR 30-CD set.

LA039

brings a recording of BRAHMS Symphony No.3 from Carl

Schuricht, very late in his career, conducting the Munich Philharmonic

Orchestra (live, Herkulessaal, Munich, May 19, 1963). There are a few

extant recordings of Schuricht’s Brahms, especially of Symphony No.2, but

the only other way to find him conducting the Third is, I believe, via the

complete SWR 30-CD set.

This account is as rough-hewn where it matters as Klemperer’s (Warner

4043382, 4 CDs), still my go-to conductor in this symphony. Both open in a

way that lets us know that they (and Brahms) mean business, with Schuricht

more expeditious than Klemperer, but there’s tenderness, too, especially in

the second movement – taken, like the other movements, at much the same

well-paced tempo as Klemperer. The recording needs a good deal more

tolerance than the Klemperer, which was recorded commercially by EMI, but

the ear soon adjusts and I enjoyed hearing this vigorous performance. Being

recorded live, it avoids the clicks and bumps which accompany the BNF

transfer of Schuricht’s Brahms Symphony No.2.

At 32:13, it’s rather short value, but the price of 10 Euros (more if you

can afford to assist what is, after all, a good cause) is not excessive. In

mp3, flac and other formats from

Legendary Archives.

Those who hate applause should be warned that there is a (very brief)

segment from an otherwise quiet audience.

LA043: Richard STRAUSS Tod und Verklärung, Op.24

[23:07], and BRUCKNER Symphony No.3 in d minor [58:42]:

Munich Philharmonic Orchestra/Hans Knappertsbusch, recorded live in the

Herkulessaal, Munich, 16 January, 1964. Here is Kna conducting the work of

two composers with whom he had long been associated, and with an orchestra

whom he had worked with for decades. Like the Schuricht Brahms, the

recording preserves the veteran conductor near the end of his career, so

even later than the late-50s Wagner with the VPO and Birgit Nilsson (Decca

4842404, download only, with the Kirsten Flagstad, Set Svanholm and SoltiTodesverkündigung from Walküre) or the 1956 Wesendonck Lieder with Kirsten Flagstad and the VPO (Decca

4684862, with Flagstad and Boult in Mahler).

LA043: Richard STRAUSS Tod und Verklärung, Op.24

[23:07], and BRUCKNER Symphony No.3 in d minor [58:42]:

Munich Philharmonic Orchestra/Hans Knappertsbusch, recorded live in the

Herkulessaal, Munich, 16 January, 1964. Here is Kna conducting the work of

two composers with whom he had long been associated, and with an orchestra

whom he had worked with for decades. Like the Schuricht Brahms, the

recording preserves the veteran conductor near the end of his career, so

even later than the late-50s Wagner with the VPO and Birgit Nilsson (Decca

4842404, download only, with the Kirsten Flagstad, Set Svanholm and SoltiTodesverkündigung from Walküre) or the 1956 Wesendonck Lieder with Kirsten Flagstad and the VPO (Decca

4684862, with Flagstad and Boult in Mahler).

The recording is more secure than the Schuricht Brahms, though no match for

a commercial recording of this date, or even the 1954 Decca recording of

the Bruckner Third with the VPO (Eloquence 4828800, 4 CDs, with Symphonies

Nos. 4, 5 and 8 –

review). Like the 1954 recording, the ‘Wagner’ symphony is presented with the

cuts which were customary at the time, but the performance shows no sign of

flagging, so, with tolerable, albeit congested sound, and a significant and

powerful filler in the Strauss, this is one of my picks from my limited

initial exploration of the

Legendary Archives

catalogue.

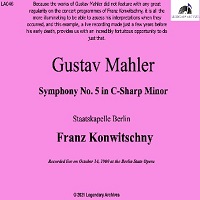

LA045: MAHLER Symphony No.5

in c-sharp minor: Staatskapelle Berlin/Franz Konwitschny – rec. Live,

Berlin State Opera, 14 October 1960 [68:56]. ADD/mono. Very little remains

available of Konwitschny’s commercial recordings, so this live recording of

Mahler’s Fifth from late in his career is of special interest. As if to

prove the thesis that performances of the fourth movement, adagietto, have become slower over the years, Konwitschny takes

just over eight minutes, where the recent Vänskä Minnesota recording lasts

12:39 (BIS-2226 SACD). I thought the BIS far too slow, and verging on the

lethargic –

review

– and John Quinn thought it a major disappointment –

review

– while Konwitschny gets all the emotion out of the movement without

milking it. (Dan Morgan was even more forthright about the Vänskä adagietto: ‘unforgiveable sluggish … stops this performance in its

tracks’ –

review).

LA045: MAHLER Symphony No.5

in c-sharp minor: Staatskapelle Berlin/Franz Konwitschny – rec. Live,

Berlin State Opera, 14 October 1960 [68:56]. ADD/mono. Very little remains

available of Konwitschny’s commercial recordings, so this live recording of

Mahler’s Fifth from late in his career is of special interest. As if to

prove the thesis that performances of the fourth movement, adagietto, have become slower over the years, Konwitschny takes

just over eight minutes, where the recent Vänskä Minnesota recording lasts

12:39 (BIS-2226 SACD). I thought the BIS far too slow, and verging on the

lethargic –

review

– and John Quinn thought it a major disappointment –

review

– while Konwitschny gets all the emotion out of the movement without

milking it. (Dan Morgan was even more forthright about the Vänskä adagietto: ‘unforgiveable sluggish … stops this performance in its

tracks’ –

review).

As with the other recordings which I have tried from Legendary Archives,

the recording requires a degree of tolerance, but the ear adjusts. There’s

brief applause fore and aft, which will put off those who dislike it.

LA047

from

Legendary Archives

[48:36] brings the biggest and most pleasant surprise of these releases: Alan Bush conducting

the Leipzig Radio Symphony Orchestra in studio recordings of VAUGHAN WILLIAMS: the Fantasia on a Theme of Thomas Tallis [13:24] (16 September 1953) and Symphony No.5 in

D [35:09] (7 February 1955). All ADD/mono. I didn’t think that VW’s music

had made an impression in East Germany as early as that, or that the

Leipzig players would have latched onto the idiom. It no doubt helped that

they had an English conductor, directing music by a friend and colleague.

The playing is not of the very finest, but Bush seems to have rehearsed

them thoroughly, and his commitment to the music makes this release

eminently worth hearing. The recording may be rather thin and dry, but not

much more so than the classic Boult recording of the Fifth for Decca. I’m

amazed to find this recording of the symphony almost as idiomatic as the

Boult, less at peace with itself, more prescient of the mood of the Sixth

Symphony, and in very tolerable sound for its age.

LA047

from

Legendary Archives

[48:36] brings the biggest and most pleasant surprise of these releases: Alan Bush conducting

the Leipzig Radio Symphony Orchestra in studio recordings of VAUGHAN WILLIAMS: the Fantasia on a Theme of Thomas Tallis [13:24] (16 September 1953) and Symphony No.5 in

D [35:09] (7 February 1955). All ADD/mono. I didn’t think that VW’s music

had made an impression in East Germany as early as that, or that the

Leipzig players would have latched onto the idiom. It no doubt helped that

they had an English conductor, directing music by a friend and colleague.

The playing is not of the very finest, but Bush seems to have rehearsed

them thoroughly, and his commitment to the music makes this release

eminently worth hearing. The recording may be rather thin and dry, but not

much more so than the classic Boult recording of the Fifth for Decca. I’m

amazed to find this recording of the symphony almost as idiomatic as the

Boult, less at peace with itself, more prescient of the mood of the Sixth

Symphony, and in very tolerable sound for its age.