FORGOTTEN ARTISTS - An occasional series by Christopher Howell

18. JONEL PERLEA (1900-1970)

Forgotten Artists index page

When I had been living in Italy just about long enough to make sense of the local record magazines, I was brought up short by a review that began something like this: “The great Mozart conductors of the twentieth century were Walter, Beecham, Karajan, Markevich, Perlea and Zecchi”. Regrettably, I don’t seem to have kept the magazine – we’re talking of 1976 or thereabouts – so I hope I’ve remembered the list correctly. The mix seems clear: two conductors from the mid-century who, in a pre-HIP age, might have topped anybody’s list, the most adulated living conductor, a major figure usually associated with other repertoire and two dark horses – Perlea and an elusive Italian pianist-conductor.

When I had been living in Italy just about long enough to make sense of the local record magazines, I was brought up short by a review that began something like this: “The great Mozart conductors of the twentieth century were Walter, Beecham, Karajan, Markevich, Perlea and Zecchi”. Regrettably, I don’t seem to have kept the magazine – we’re talking of 1976 or thereabouts – so I hope I’ve remembered the list correctly. The mix seems clear: two conductors from the mid-century who, in a pre-HIP age, might have topped anybody’s list, the most adulated living conductor, a major figure usually associated with other repertoire and two dark horses – Perlea and an elusive Italian pianist-conductor.

Having thrown down the gauntlet, the writer then got down to his main business of discussing the latest Karajan offerings. The list reverberated in my mind over the years but only now have I finally tracked down enough material to examine Perlea’s claims.

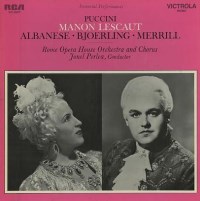

Perlea is nevertheless a conductor with at least a subliminal presence in the discographic world. If you are a fan of post-war opera stars, you will have collected a good many recordings directed by conductors who apparently seem to have been eternally destined for a supporting role. Perlea may, at first sight, seem one of these. RCA engaged him only for operatic work and, specifically, for three sets featuring the tenor Jussi Björling – Manon Lescaut (1954), Aida (1955) and Rigoletto (1956). If you look up reviews of these sets, including some on our own site, you will find that Perlea’s work is often singled out in a way that of Cellini, Votto, Erede or Molinari-Pradelli tends not to be. Nevertheless, RCA did not engage Perlea again – for reasons that will be examined later – until 1965, when he conducted a classic set of Lucrezia Borgia with Caballé in the title role.

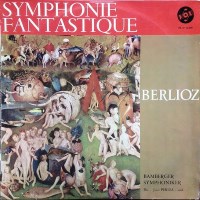

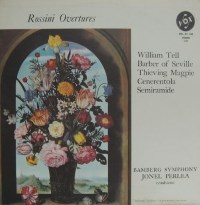

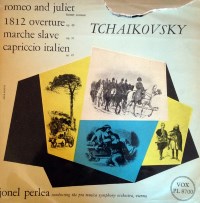

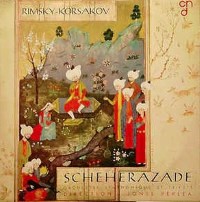

There is another way in which Perlea subliminally entered many a semi-musical household. In the late 1960s, Fratelli Fabbri initiated a series of lavishly illustrated coffee-table magazines called “The Great Musicians”. The articles and the illustrations were actually quite good. Popped into the back, almost as an after-thought, was a 10-inch LP. Most of these were licensed from old Vox recordings, grittily pressed. It was generally agreed that the record itself was the Achilles’ heel of the enterprise, and quite a few were conducted by Perlea. It would not have occurred to many at the time that, one day, we might be listening seriously to these old Vox recordings – those by Perlea no less than those by Horenstein – for the evidence they give of a distinctive interpretative point of view.

As ever with this series, I am infinitely grateful to the blogs and YouTube channels, as well as a fellow enthusiast, that have made it possible for me to hear a fairly representative selection from a recorded legacy that proved far larger than I had imagined. If, for the most part, I do not specifically name the bloggers and YouTube posters, this is because these sites have a way of coming and going. Just in the few years since I began accumulating this material, several blogs and YouTube channels have disappeared, while others remain visible but with the links dead. Please assume, therefore, that I am discussing the performances and recordings, not specific transfers of them.

As for the information on Perlea’s life and career, I list in footnotes the websites I have found useful, again with the proviso that they have a way of appearing and disappearing. Information is sometimes contradictory. I have tried to make sense of it. If this article induces others to provide information, corrections and memories, these will be gratefully appended.

Early years and career 1900-1945

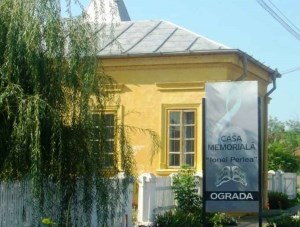

Jonel Perlea was born on 13 December 1900 in Ograda, a village on the Romanian plain (1)

(birthplace - see right). His father was Romanian, his mother was German. Perlea senior was apparently a good amateur musician. He died when Jonel was only ten and his widow returned to her family in Munich. Thus, a Romanian-German dualism characterized the future conductor, in his education as well as in his family background. His heart surely remained in Romania; at the age of twelve he wrote an “Ograda Waltz” and his first public appearance – as performer and composer – was in Bucharest on 17 October 1919. Nevertheless, his musical studies were in Munich and Leipzig, where Paul Graener was his principal teacher. Some sources suggest he also studied with Max Reger. Reger certainly taught at the Leipzig Conservatoire, but he died in 1916, so any contact would have been minimal.

Jonel Perlea was born on 13 December 1900 in Ograda, a village on the Romanian plain (1)

(birthplace - see right). His father was Romanian, his mother was German. Perlea senior was apparently a good amateur musician. He died when Jonel was only ten and his widow returned to her family in Munich. Thus, a Romanian-German dualism characterized the future conductor, in his education as well as in his family background. His heart surely remained in Romania; at the age of twelve he wrote an “Ograda Waltz” and his first public appearance – as performer and composer – was in Bucharest on 17 October 1919. Nevertheless, his musical studies were in Munich and Leipzig, where Paul Graener was his principal teacher. Some sources suggest he also studied with Max Reger. Reger certainly taught at the Leipzig Conservatoire, but he died in 1916, so any contact would have been minimal.

In 1922 Perlea began to work as a répétiteur in Leipzig, moving to Rostock in 1925. Also in 1922, his fellow Romanian Georges Enescu advised him never to give up composing, and in 1926 Perlea won the Georges Enescu composition prize with a string quartet. The quartet was published and achieved a number of performances.

Perlea then returned to Romania, and, had it not been for the war, would surely have maintained his base in that country. After a period with the Romanian Opera of Cluj-Napoca in the late 1920s – different accounts give different dates – he appeared with the Bucharest National Opera, of which he was General Director from 1932 to 1936. During this period he gave several local premières, including “Die Meistersinger” and “Der Rosenkavalier”. He also conducted some performances of “Boris Godunov” with Chaliapin in the title role. Meanwhile, he was making a reputation outside the opera house, and was conductor of the Bucharest Radio Orchestra from 1936 to 1944. Teaching also played a major role throughout his career, and in 1941 he was appointed professor of conducting at the Bucharest Royal Conservatoire.

What looked like an upward success story came to a halt just as the war was ending. In 1944, Perlea was travelling with his wife to Paris for a conducting engagement. They were stopped in Vienna. King Michael of Romania had switched his support to the allies, depriving Nazi Germany of a valuable source of petroleum. The Nazi authorities demanded that Perlea should broadcast to the Romanian people, urging them to keep faith with the Nazis. Perlea refused and was placed under house arrest. Accounts vary as to the ultimate consequence of this refusal. Some say he remained under house arrest till the end of the war, others claim he was sent to the concentration camp of Mariapfarr. Strangely, I find no trace of the existence of a concentration camp at Mariapfarr, an Austrian village near Salzburg, except in biographies of Perlea and one or two other Romanians. Maybe some reader can shed light on this?

Perlea was not to return to Romania till 1969.

Perlea the composer

Our earliest aural glimpse of Perlea is, somewhat surprisingly, as a composer. On May 5th 1939, George Enescu conducted the New York Philharmonic in what appears to have been a slimmed down version of Perlea’s “Variations on an Original Theme”. Perlea took up composition again in his last years and must have conducted some of his works, enabling Gunther Schuller to discover that he was “a fine composer, more than just a conductor-composer” (4). Nevertheless, he was mainly active in this role during the pre-war years, so this seems a good moment to discuss such of his works that I have heard.

It is not clear how much of the “Variations” Enescu actually conducted. The fellow enthusiast who supplied me with this recording – which has occasionally been available in Enescu anthologies – says it has variations 3, 4 and 7. To my ears, there are four sections, with the first sounding as if it ought to be the theme itself. The recording is pretty obviously cut off, suggesting that, if Enescu omitted variations 1, 2, 5 and 6, he did play at least one more.

It is clear from the torso that Perlea had a wide and colourful orchestral palette, with considerable use of the vibraphone. His language is tonal, but pushing tonality to the limit – “Gurrelieder” filtered through Szymanowski and Enescu himself might give an idea. Much of the music is langorous, but folksy elements emerge in variation 7.

The recording is dim, but anything conducted by Enescu is of interest. He consistently clarifies the teeming textures, leading the listener’s ear towards the part where the principal melodic interest lies and ensuring that an overall line emerges.

These interpretative qualities are less evident in a 1998 recording of the “Don Quixote” Symphonic Scherzo in which Paul Popescu conducts the Romanian Radio Symphony Orchestra. The impression is of a capable conductor and orchestra wading their way gamely through a work they are learning as they go. This is what we usually get with complicated out-of-the-repertoire works and, as ever, gratitude for hearing the music at all is tempered with doubts as to whether it was really worthwhile. It would be interesting to know what aspect of “Don Quixote” Perlea is illustrating. The language and palette – minus the vibraphone – are much as before, with an injection of what seems to be Debussy recollected in a nostalgic vein. It’s so far from a Scherzo that I can’t help wondering if it is really meant to be like that. The 3-minute section starting around 11 minutes sounds as if it ought to be mercurial, but it isn’t here. I couldn’t help wishing someone like Munch or Markevich could have come along to fire things up a bit. The concluding 14 minutes are luxuriantly slow, with a long solo for bass clarinet against shimmering strings. It seems a bit indulgent, but maybe it wouldn’t if things had sizzled more earlier on. The last couple of minutes are undeniably beautiful.

These interpretative qualities are less evident in a 1998 recording of the “Don Quixote” Symphonic Scherzo in which Paul Popescu conducts the Romanian Radio Symphony Orchestra. The impression is of a capable conductor and orchestra wading their way gamely through a work they are learning as they go. This is what we usually get with complicated out-of-the-repertoire works and, as ever, gratitude for hearing the music at all is tempered with doubts as to whether it was really worthwhile. It would be interesting to know what aspect of “Don Quixote” Perlea is illustrating. The language and palette – minus the vibraphone – are much as before, with an injection of what seems to be Debussy recollected in a nostalgic vein. It’s so far from a Scherzo that I can’t help wondering if it is really meant to be like that. The 3-minute section starting around 11 minutes sounds as if it ought to be mercurial, but it isn’t here. I couldn’t help wishing someone like Munch or Markevich could have come along to fire things up a bit. The concluding 14 minutes are luxuriantly slow, with a long solo for bass clarinet against shimmering strings. It seems a bit indulgent, but maybe it wouldn’t if things had sizzled more earlier on. The last couple of minutes are undeniably beautiful.

“Don Quixote” was included on a disc dedicated to Perlea, composer and conductor, by Romanian Radio. The same CD also had four Lieder sung in 1984 by the soprano Georgeta Stoleriu, accompanied on the piano by Marta Joja. The disc gives the titles in Romanian and in English but they are sung – and were presumably composed – in German. It would be a real treat to know what they are about, beyond the bare titles.

The meat of the offering is the 3 Lieder op.10. In the first of these, “Vigil”, the lack of any explanation is particularly felt. It seems indulgently doleful, but perhaps there is a point to it. The second, “Longing”, is such a strikingly beautiful song that it makes an impact despite the odds stacked against it. Perlea proves himself here a master of soaring soprano lines to rival Richard Strauss – which is saying something. The last song, “Departure”, is much briefer, and makes an energetic conclusion. It is nevertheless one-upped here by the separate song “On your name day”, again brief but a “good sing”. Stoleriu manages the songs very well, and Joja is a fine accompanist as far as can be heard – she seems to have been recorded in the next room. The case for Perlea as a composer of Lieder in a rich post-romantic idiom seems a strong one – I hope he wrote more than just these.

Perlea in Italy - La Scala

We left Perlea in the hands of the Nazis. He was not able to resume his work in Bucharest. His anti-Nazi credentials would seem unassailable, but the Communist government installed in Romania soon after the war evidently felt he would be an awkward customer to have around. He was refused a visa to return home.

In the first place he established himself in Italy and soon found work coming his way. Toscanini heard him conduct the Santa Cecilia Academy Orchestra and immediately offered him an engagement at La Scala. There followed a brief but intensive period of collaboration with Italy’s foremost opera house. At the time of writing, La Scala’s website provides full details of all performances – opera and concerts – given from 1951 onwards. This just postdates most of Perlea’s work. From another source, I have found details – I hope complete – of his opera performances (2). I suspect he may have conducted more concerts than I am able to trace. Perlea’s opera performances at La Scala were as follows – the dates are those of the first night.

1947 (29 January):

Saint-Saëns: Sanson et Dalila

Ebe Stignani (Dalila), Fiorenzo Tasso (Sansone), Abelardo Martelli (messaggero), Erminio Benatti (1° filisteo), Ugo Savarese (Sommo sacerdote), Carlo Forti (Abimelecco), Cesare Siepi (vecchio ebreo), Giuseppe Menni (2° filisteo), ballerinas: Luciana Novaro, Gino Pessina, producer: Mario Frigerio, choreographer: Rosa Piovella Ansaldo: scenes: Camillo Parravicini

1947 (17 Aprile)

Mozart: Così fan tutte

Suzanne Danco (Fiordiligi), Tatiana Menotti (Despina), Giulietta Simionato (Dorabella), Marcello Cortis (Guglielmo), Pietre Munteanu (Ferrando), Fritz Ollendorff (Don Alfonso)

1947 (11 June)

Gluck: Orfeo ed Euridice (Berlioz version)

Suzanne Danco (Euridice), Loretta Di Lelio (according to the archives, but replaced by Lia Origoni) (Amore), Ebe Stignani (Orfeo), scenes: Gio Ponti

1947 (10 September)

Mussorgsky: Boris Godunov (Rimsky-Korsakov version)

Bianca Baessato (Xenia), Giuseppina Sani (nutrice), Rina Corsi (Marina), Dora Minarchi (Teodoro), Ebe Ticozzi (ostessa), Aleksandr Vesselovskij [Alessandro Wesselovsky] (Vassili Sciuiskij), Tomaso Spataro (Grigori-Dimitri), Giuseppe Nessi (Missail), Giacinto Sgaravato (Kruscev), Giuseppe Zazzetta (boiardo), Cesare Masini-Sperti (innocente), Attilio Barbesi (Andrea Celkalov), Aristide Baracchi (Lavitzki), Aldo Bacci (Cernikovskij/Nikitich), Tancredi Pasero (Boris Godunov), Boris Christoff (Pimen/Rangoni), Nicola Rossi-Lemeni (Varlaam), Eraldo Coda (guardia frontiera/voce interna/Mitjuscia)

1947 (7 October)

Giordano: Siberia

Adriana Guerrini (Stephana), Disma De Cecco (fanciulla), Ebe Ticozzi (Nikona), Antonio Annaloro (Vassilij), Gino Del Signore (principe Alexis), Cesare Masini-Sperti (Ivan), Abelardo Martelli (sergente/Ipranivick), Erminio Benatti (cosacco), Giovanni Inghilleri (Gléby), Eraldo Coda (Walinoff/capitano), Aldo Bacci (governatore/Walitzin), Michele Cazzato (Miskinski/starosta), Aristide Baracchi (invalido), Attilio Barbesi (commissario/ispettore)

1948 (7 maggio) Double bill:

Renzo Bianchi: Gli Incatenati

Clara Petrella (figlia), Wanda Madonna (madre pazza), Cesare Masini-Sperti (giovane), Vasco Campagnano (capo), Piero Campolonghi (padre), Eraldo Coda (sbirro), Enrico Campi (vecchio), producer: Alessandro Brissoni, scenes: Antonio Molinari

Strauss R: Salomé

Lili Djanel (Salome), Ebe Ticozzi (paggio), Maria Benedetti (Erodiade), Silvana Zanolli (schiava), Fiorenzo Tasso (Erode), Gino Del Signore (Narraboth), Giuseppe Nessi (1° giudeo), Cesare Masini-Sperti (2° giudeo), Erminio Benatti (3° giudeo), Mario Carlin (4° giudeo), Gino Penno (1° nazareno), Piero Guelfi (Jochanaan), Aldo Bacci (cappadoce), Eraldo Coda (5° giudeo), Dario Caselli (1° soldato), Carlo Forti (2° soldato), Enrico Campi (2° nazareno), producer: Hans Zimmermann, scenes: Isaia Colombo

1948 (7 October)

Massenet: Werther

Dora Gatta (Sofia), Giulietta Simionato (Carlotta), Silvana Zanolli (Kathchen), Giacinto Prandelli (Werther), Cesare Masini-Sperti (Schmidt), Piero Campolonghi (Alberto), Enrico Campi (Johann), Eraldo Coda (podestà), Aldo Bacci (Brulmann)

1949 (31 January)

Beethoven: Fidelio

Delia Rigal (Leonora-Fidelio), Hilde Güden (Marcellina), Mirto Picchi (Florestano), Angelo Mercuriali (Giacchino), Giuseppe Taddei (Don Pizarro), Boris Christoff (Rocco), Dario Caselli (Don Fernando), producer: Oscar Fritz Schuh, scenes and costumes: Felice Casorati.

1952 (2 April)

Mozart: Il Ratto dal Serraglio

Maria Callas (Konstanze), Tatiana Menotti (Blonde), Giacinto Prandelli (Belmonte), Petre Monteanu (Pedrillo), Salvatore Baccaloni (Osmin), Nerio Bernardi (Selim). Scenes by Nicola Benois.

According to Grigoriu, Perlea also conducted La Traviata, Turandot and Lohengrin at La Scala, but this seems to be an error. The annals clearly list performances of these operas during those years, but with other conductors. Possibly Grigoriu is confusing performances that Perlea conducted elsewhere in Italy. He conducted Turandot with Maria Callas at the Naples San Carlo Theatre in a run of four performance opening 12 February 1949, for instance.

The concert appearances by Perlea listed at La Scala’s site – limited to those from 1951 onwards – are listed below. Here too, the date may be the first of a run of two or three performances:

1951 (17 August)

Cherubini: Anacreonte Overture

Beethoven: Symphony no.3 “Eroica”

Wagner: Parsifal Prelude

Mussorgsky-Ravel: Pictures at an Exhibition

1951 (25 October)

Debussy: Nocturnes

Malipiero, Riccardo: Cantata Sacra (first performance)

Haydn: Symphony no.94 “Surprise”

Ravel: Valses Nobles et Sentimentales

Glinka: Russlan and Ludmila Overture

Irma Lucia Bozzi (soprano), Coro della Scala (chorus master Vittore Veneziani)

1957 (22 June)

Cherubini: Anacreon Overture

Debussy: La Mer

Liadov: 8 Russian Folk Songs

Tedeschi, Alberto Bruni: Messa per la Missione di Nyondo (first performance in Milan)

Mariella Angioletti (soprano), Aldo Bertocci (tenor), Alfredo Giacomotti (bass) Ottavio Fanfani (reciter), Corro della Scala (chorus master: Norberto Mola).

All the opera performances were sung in Italian – this was actually the last time “Fidelio” was heard at La Scala in the vernacular. Only two years later the Wunderkind Karajan conducted a production in German.

A story is attached to the “Orfeo ed Euridice” production. According to the annals, the part of Amore was sung by Loretta Di Lelio, but it seems that she pulled out just before the dress rehearsal. Her place was taken by a young singer called Lia Origoni who, in her innocence, failed to observe the standard practice that only Orfeo takes a curtain call at the end of Act I. The Orfeo, Ebe Stignani, rewarded her apparent impertinence with a hearty kick backstage. Perlea was witness to this and roundly castigated Stignani, declaring that “we should all be grateful to Lia Origoni for saving the show”. Fortunately, subsequent performances went harmoniously and this opera was among the events chosen to celebrate a visit to Italy by Eva Peron (3).

The pattern of Perlea’s collaboration with La Scala is clear. For two years, from January 1947 to January 1949, he conducted a wide repertoire and, in 1947 particularly, had a more consistent presence than any other conductor. Thereafter, he conducted a single opera, in 1952, and that only as a substitute for an ailing Issay Dobrowen. He was still conducting concerts in 1951 – I am assuming, maybe wrongly, that he also conducted concerts in the years 1947-1949 – and then returned just once, in 1957.

Most resumés of La Scala’s postwar history seem reluctant to mention Perlea at all. He does not appear to have held any specific post, such as Music Director, Artistic Director or Principal Conductor. In view of his recommendation by Toscanini, this rather looks like a variant on what happened in Berlin, where Perlea’s compatriot Sergiu Celibidache kept the seat warm for Furtwängler, but failed to reap the hoped-for reward.

Obviously, Toscanini’s situation was very different, politically, from Furtwängler’s. Given his enormous prestige, his freedom from all taint of collaborationism and the disgraceful treatment he had received from the Fascists, probably no one in Italy would have denied that he should return to his old post at La Scala if he wished. Hence the willingness to give full rein to a Toscanini protégé while there was still some hope that the great man himself would take over. It soon became clear, however, that, given his considerable age, Toscanini would be unable to do more than conduct the occasional concert. Thus the stage was set for new manoeuvres.

There has always existed a strong feeling in Italy that La Scala, of all Italian opera houses, should have an Italian as its Music Director. Even in recent years, the Barenboim period was largely seen as an unwelcome interlude. And after all, La Scala still had – theoretically – an Italian Music Director. Victor De Sabata had taken over following Toscanini’s forced exit in 1929. A very different type of conductor from Toscanini, those who felt the latter too inflexible believed De Sabata was the greatest living Italian conductor. Even for those who appreciated Toscanini’s rigour, the obvious candidate for La Scala, if it couldn’t have Toscanini, in 1947 as in 1929, was De Sabata. The only problem might have been a political one.

It was Toscanini’s unwavering opposition to the Fascist dictatorship that had led to his departure after the “schiaffo di Bologna” in 1929. Any conductor who took his place under such circumstances was implicitly associating himself with the regime. De Sabata, in any case, made no secret of his friendship with Mussolini, and even conducted private performances in the dictator’s own home. In spite of his Jewish origins, he managed, too, to be a welcome guest in Germany until at least 1939.

Germans who had collaborated with the Nazis had to be de-Nazified after the war. I have never heard tell of any similar de-Fascistification process in Italy and I presume that any such programme must have been a pretty mild affair. Many from the artistic world conveniently “discovered”, after 1945, that they had really been Communists all along. De Sabata never stooped to this, but there was no real obstacle, once it was clear that Toscanini would not return to the post, to easing De Sabata back into a position he had theoretically never relinquished. Most reference books, in fact, list him as Music Director of La Scala from 1929 to 1953 uninterruptedly, and Artistic Director till 1957. A few list brief tenures in the 1940s, notably by Mario Rossi and Franco Capuana. None mention Perlea.

Clearly Perlea, like Celibidache in Berlin, had become an uncomfortable presence. The best thing was to quietly let him go and pretend he’d never been. The question remains, whether he had helped his departure by lending hostage to fortune in some manner.

This might have come about in two ways. Firstly, he may have got uppity about the operas assigned to him. As we shall shortly see, he certainly did this at the Metropolitan a year or so later. So maybe he did this at La Scala too.

The other question is – how did his performances stand up compared with those that Toscanini or De Sabata might have given? Some of the operas he conducted were, in fact, taken up by De Sabata over the following few years. Even one lacklustre showing would have provided ample ammunition for those wishing to be rid of him.

A full-scale biographer of Perlea would doubtless find time to sift through contemporary press comment and to establish whether any of Perlea’s performances failed to reach the desired standard – or, at any rate, whether critical opinion thought they did. A rather curious discography by Grigoriu – rich in omissions and errors – lists live recordings that have circulated on obscure labels, “not all listed in the international discography”. According to this, recordings exist of Perlea’s La Scala performances of Così fan Tutte, Boris Godunov, Werther and Die Entführung aus dem Serail. I’m inclined to feel that I’ll believe in these performances when I hear them. It really does seem impossible that a recording of Maria Callas in Die Entführung would not have circulated widely if it existed, whatever the sound quality. Still, if any reader can throw light on these recordings, better still tell me where I can get them, I would be delighted to know. They should be able to demonstrate, for better or for worse, the quality of Perlea’s work at La Scala.

Apart from this, we have just two tantalizing souvenirs. These were set down by Decca in 1947. The most revealing is that of the Ballet Music from Saint-Saëns’ Samson et Dalilah. It was set down on 19 July with Victor Olof as producer. Samson et Dalilah had been Perlea’s first opera at La Scala. He conducts with real flair and a sense of sinuous oriental colour – more so, perhaps, than in his nevertheless very good 1956 Vox recording of it with the Würtemburg State Symphony Orchestra. He also obtains some brilliant articulation which Toscanini would surely have approved of – La Scala’s orchestra is shown to have been a fine band at that time. What differentiates this version completely from the Vox one, however, is the vocal, swooning strings in the central section. This is a type of playing, generally thought of as “pre-war”, which lingered on in Italy into the early 1950s. It is quite probably what Saint-Saëns would have expected, but we can hardly blame Perlea if the Würtemburg orchestra provided just good, clean playing at the same point.

Decca’s other La Scala offering was a souvenir of Suzanne Danco’s Fiordiligi in Così fan tutte – Come scoglio. Così was still a “problem opera” back then so, rather than couple it with Fiordiligi’s other aria – if it was sung at La Scala, for Perlea was quite a cutter, as we shall see – they had her sing Voi che sapete from Le nozze di Figaro. Both were set down on 30 July 1947. Danco was much associated with Fiordiligi – her Italian debut had been in this role (Genoa 1941). Her first appearance with the Glyndebourne Festival Opera was also as Fiordiligi, at the Edinburgh Festival under Gui in 1948, so this recording provided a neat visiting card.

I have never much warmed to Danco’s art. Anna Russell once referred, cruelly but pertinently, to the “Nymphs and Shepherds, or pure white” style of singing, meaning, I suppose, the kind of British soprano typified by Isobel Baillie. The Franco-Belgian “pure white” style was a little different but I find it similarly dated. Nevertheless, I cannot deny the security and cleanness of her singing here – though she lacks a trill. The orchestra is neat and crisp. Danco’s Cherubino is well known from the famous Erich Kleiber recording. The main difference here is Perlea’s big ritardando before the restatement of the principal theme.

Decca have made precious few recordings at La Scala over the years. Maybe they thought they would be onto a good thing by grabbing La Scala’s up-and-coming new conductor. History went differently.

Perlea in Italy – after La Scala

Though Perlea faded from view at La Scala, he was in considerable demand elsewhere in Italy for most of the 1950s. He gave the local premières of Tchaikovsky’s Mazeppa and The Maid of Orleans and Richard Strauss’s Capriccio (Genoa 1953), as well as championing Nino Rota’s I due timidi and, notably, Henze’s Boulevard Solitude (Naples 1954). I due timidi was originally a radio opera, premiered under Franco Ferrara in 1950. Rota’s reworking for the stage was heard under Perlea at Palermo in 1955.

At least four Italian opera performances under Perlea have been issued in some form or can be found on YouTube. The ever-hopeful Grigoriu lists several more but I will limit discussion to the four I have heard. The technical quality, I must say, does not greatly encourage the search for others.

Mozart’s Le Nozze di Figaro was given at the Teatro San Carlo di Napoli on 20 February 1954 with a cast consisting of Italo Tajo (Figaro), Alda Noni (Susanna), Giulietta Simionato (Cherubino), Renata Tebaldi (La Contessa d'Almaviva), Scipio Colombo (Il Conte di Almaviva), Giuliana Raimondi (Barbarina), Endré von Koreh (Bartolo), Agnese Dubbini (Marcellina), Piero De Palma (Don Basilio), Cristiano Dalamangas (Antonio) and Gianni Avolanti (Don Curzio).

This performance has been issued by Hardy Classics (HCA 6017-2). Up to a point, they play fair. Most of the Act II finale, and the whole of the Act IV finale, are declared missing. They admit to an “unevenness of pitch”. The sheer ghastliness of what this entails can be savoured in the “letter” duet between the Countess and Susanna. The piece starts with good sound at a nice, relaxed tempo, and Alda Noni sings her opening phrase very attractively. When Tebaldi enters the whole acoustic changes, seemingly coming from an adjacent bathroom, the pitch rises between a quarter and half a tone and, obviously, the tempo spurts ahead with it. Then Susanna sings another phrase and the picture is normalized. And so it goes on. We are therefore getting a good impression of Noni’s performance, a falsified one of Tebaldi’s. Ives-like, I rather wondered what it would sound like if, when they sang together, each continued at their different pitch and speed. Obviously, it didn’t happen. I’m racking my brains to think how the tape could have systematically gone faster for one singer than for the other but I can’t think of any explanation. Nor can I imagine how, in the course of a piece lasting about three minutes, the parts regarding one singer are so much more damaged than those regarding the other. My conclusion is that the recording had to be pieced together from at least two different tapes, one much better than the other – for when it actually is good, it’s remarkably good for its age – and, above all, recorded on tape recorders that went at different speeds. But can’t modern technology straighten these things out? It would be a terrible job for someone, so the first question would be, is it worth it?

Well, we have here the only surviving testimony, so far as I know, to either of the two Mozart roles sung by Renata Tebaldi – the other was Donna Elvira. Her two arias emerge fairly unscathed – just a few blips. Her steady production and sheer vocal beauty grace “Porgi, amor” and the first part of “Dove sono” and it’s much purer – with less scooping – than one might have supposed. The faster section of “Dove sono” show an ability to toss off light, agile music that she might have profitably developed further. In her recitatives, those that are at pitch, and her ensemble work, with the same proviso, she enters fully into the character. So yes, this is one reason for attempting further restoration of the recording.

Another reason, and the other Mozartian dark horse, is Giulietta Simionato as Cherubino. Unfortunately both her arias are above pitch. “Non so più” is made to go like the wind and “Voi che sapete” is similarly made to sound about the fastest version I’ve ever heard. Even at the right pitch, they must surely be on the urgent side, but here I must suspend judgement.

Alda Noni’s recitatives, in particular, well above pitch, are made to sound squeaky and breathless. But “Venite, inginocchiatevi” is at the right pitch and a relaxed tempo and she sounds lovely. So she does in “Deh, vieni”, taken fairly slowly. The Barbarina and Marcellina sound less happy.

Of the principal men, Italo Tajo, mostly known on disc in smaller roles, is fine when we hear him at the right pitch, and so is Scipio Colombo as the Count. Piero De Palma offers a very caricatured Don Basilio. Unusually, he gets his aria – the only major cut is Marcellina’s aria – but to little avail. Bits are at the right pitch and sound good, but they alternate with bits up about a tone. At the end the orchestra races still further and the final chord is up a third.

At this point, it is difficult to reach any conclusion about Perlea himself. When the pitch is right, the performance has a rococo grace and is even a tad too relaxed, though with light textures and well-sprung rhythms. Other bits of the score are jacked up in pitch and tempo to sound absolutely manic – compare the Act II trio (up in pitch) with the Act III sextet, which unfolds almost too patiently. I just wish the surviving material could be handed over to someone like Mark Obert-Thorn who might be able to sort the pitches out.

The following year, 1955, Perlea was back at San Carlo, Naples, with Massenet’s Manon. The cast, singing in Italian, was Clara Petrella (Manon), Ferruccio Tagliavini (Le Chevalier Des Grieux), Saturno Meletti (Lescaut) and Vito De Taranto (Le Compte des Grieux).

Given that Perlea could be a vicious cutter, the listener’s first reaction as the Prelude leads straight into the second scene – and the first act also lacks its final scene – will be “he’s at it again!” It’s not quite that simple. Go to Vittorio Gui’s 1952 Italian-sung performance (RAI Milano with Carteri, Prandelli, Poli and Clabassi) and you’ll find that the cuts are the same. So they are in an Italian-sung 1966 RAI film under Maag (from Modena with Freni, Garaventa and Bruson). So, presumably, are they in a 1969 La Scala performance in Italian under Maag (with Freni, Pavarotti and Panerai), which I haven’t heard – but the cuts are described in an MWI review. Another common feature is that the spoken dialogue is replaced with recitative.

All this is discussed very fully in a doctoral dissertation “The Impact of Jules Massenet’s Operas in Milan 1893-1903” by Matthew Martin Franke (Chapel Hill 2014), available on Internet. What we have is not an arbitrary piece of scissors-work by these three conductors – though Perlea makes a few more snips of his own – but an “Italian Manon”, an alternative version of the opera prepared for Italian use. The extent of Massenet’s own involvement in the omissions and reordering will probably never be known, since the archives of the publisher Sonzogno, which possibly conserved such information, were destroyed in the Second World War. It has been definitely established that Massenet himself wrote the recitatives to replace the spoken dialogue. He set them in French, but the general assumption is that he did so in the expectation that they would then be adapted for the Italian edition. They were never taken up in French performances.

It must be said that the “Italian Manon” has something to be said for it. Firstly the recitatives, which should please those who, like Tchaikovsky – and myself, if it matters – are not entirely happy with spoken dialogue in what is essentially a late-romantic opera with a tragic ending. Could anyone really not prefer singing voices soaring over the off-stage choral “Magnificat” in the Saint-Sulpice scene rather than spoken interjections? There is, of course, no reason why these recitatives could not be reinserted into uncut performances in French, but this would be a hybrid version and modern musicology does not approve of such things.

As for the cuts, the principal one, apart for the omissions in Act 1 already mentioned, is the total exclusion of Act III Scene 1, with Acts IV and V treated as one to make an opera in four acts. There are also fairly substantial snips in what now becomes Act IV Scene 1. All this makes for an opera lasting around two hours – slightly less under Gui and Perlea, slightly more under Maag. The famous Monteux set and the well-regarded modern version under Pappano last 40-45 minutes more. Dare I suggest that two hours of music, plus intervals, might be enough for an opera that, for all its beauties, hardly has the density of Tristan und Isolde?

Perplexities remain. The Italian vocal score, published by Heugel in France and Sonzogno in Italy (and currently downloadable from IMSLP) contains more than is actually heard under Gui, Perlea and Maag. In particular, Act III Scene 1 is present. Nevertheless, Franke has been unable to trace any Italian performance of the opera which actually included that scene. As far as can be told, the opera that was first heard in Italy at the Teatro Carcano of Milan in 1893 was the opera that Italians continued to hear until original-language performance became the norm.

Given that the “Italian Manon” is a freestanding version, prepared in some sort of collaboration with Massenet himself, and given that the 1969 La Scala production probably marked its swansong, it would be nice to have a decent recording of it for reference purposes.

The recording balance is the main reason why the 1955 Naples production won’t fill the bill. It seems to have been recorded by someone sitting close to the orchestra, and well to one side of the theatre. At best, the singers can just about be heard. For entire long sections, one strains one’s ears to hear Tagliavini, who frequently seems to be singing off-stage entirely.

This is a pity, since there is every indication that Perlea was just as much in sympathy with Massenet’s Manon as his RCA recording proved him to be with Puccini’s Manon Lescaut. He conducts with vitality and passion, but keeping within French bounds – the otherwise excellent Gui occasionally strays into Mascagni territory. Perlea’s pacing of the Saint-Sulpice scene is particularly inspired – flexible and atmospheric but also well-structured.

Clara Petrella was known as a “singing-actress”. This label often carries the implication – as in the case of Magda Olivero – that the voice was not inherently anything special. I’m not sure that this recording offers any basis for assessing her vocal beauty. She has a considerable, but well-controlled vibrato, her production is firm, her intonation is true. She is sometimes rather free rhythmically, after the verismo manner, and occasionally catches Perlea out. She is fully in the part and is moving in the last scene.

Tagliavini has the idiosyncratic way with rhythm common to many great Italian tenors of the past, but does not carry it to excess. He can produce a full, ringing sound but his particular speciality is a honeyed head-voice. “En fermant les yeux” is a miracle of control and is greeted by such a farmyard of applause – a herd of cows and at least two elephants appear to have been in the theatre that evening – that it has to be repeated. Tagliavini fans might seek out a performance he gave in Rome Opera Theatre in 1957 under Napoleone Annovazzi and with Victoria de los Angeles as Manon (yes, in Italian). Reports suggest you might hear the singer better.

Under the circumstances, the Gui performance, in fair radio sound for 1952, is probably a better bet if you want to hear the “Italian Manon”. Rosanna Carteri and Giacinto Prandelli are less individual but are fully in their parts. Your only chance of seeing an “Italian Manon” is the 1966 Modena film.

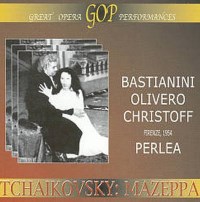

As stated above, the Italian première of Tchaikovsky’s Mazeppa was given by Perlea. This was at the Maggio Musicale Fiorentino on 6 June 1954. The singers were Ettore Bastianini (Mazeppa), Magda Olivero (Mariya), Boris Christoff (Kochubey), Mariana Radev (Liubov), David Poleri (Andrei), Jorge (Giorgio) Algorta (Orlik), Fausto Flamini (Iskra) and Piero De Palma (Drunken Cossack). The performance was issued on LP on Rococo RR 1016, Estro Armonico EA 046 and Cetra “Opera Live” LO 43. It can currently be found on YouTube.

As stated above, the Italian première of Tchaikovsky’s Mazeppa was given by Perlea. This was at the Maggio Musicale Fiorentino on 6 June 1954. The singers were Ettore Bastianini (Mazeppa), Magda Olivero (Mariya), Boris Christoff (Kochubey), Mariana Radev (Liubov), David Poleri (Andrei), Jorge (Giorgio) Algorta (Orlik), Fausto Flamini (Iskra) and Piero De Palma (Drunken Cossack). The performance was issued on LP on Rococo RR 1016, Estro Armonico EA 046 and Cetra “Opera Live” LO 43. It can currently be found on YouTube.

The fact that this was the first performance in Italy of Mazeppa lends a certain interest to the recording, which I take to be somebody’s taping of a broadcast. For what it is, it doesn’t sound too bad, though the voices become faint when the producer has them sing at the back of the stage – or at least, that is how I interpret what I hear. Nonetheless, it is possible to gain a reasonable impression of the performance. It is also good enough to suggest that Mazeppa, however little performed, is a fine and effective opera.

Nowadays, obviously, we expect to hear the original language. Nevertheless, there are a number of reasons why opera buffs might still want to hear this performance.

The first of them is the Mariya of Magda Olivero (1910-2014). Renowned as an artist who carved out her own niche in an epoch dominated by Callas and Tebaldi, she was famously under-recorded. In a stage career stretching from 1932 to 1981, with occasional concert appearances even into her nineties, she took part in only two official complete opera sets: “Turandot” (as Liù) in 1938 and “Fedora” in 1969. Fortunately, Italian Radio (RAI) had her sing a number of major roles. These and other broadcasts have become collector’s pieces over the years.

This recording is certainly collectible, but it also explains why recording companies found her problematic. She is often referred to as a “singing actress”, as compared with other operatic stars who basically stand there singing, with the occasional waddle around the stage at the producer’s insistence. The definition carries with it the implication that, maybe, there was always something about her that you’d miss if you weren’t there in the theatre to hear her. This is probable, but it is likely to remain an article of faith. What is evident here is that her very detailed, deeply felt conception of the music led to a certain breaking up of phrases where we might prefer to hear the long line. If you compare her with the two “singing-singers” in this performance, Bastianini and Poleri, their words are clear but are always part of the long vocal line. Olivero’s line tends to come in bulges, a fact that is probably compounded by the way in which this recording loses the softer tones. Nevertheless, her voice was a beautiful one at this stage in her career – by the time of her Fedora it had become a little jaded. There is a golden gleam on it and the expressive bulges are under tight control. Contrast them with the Liubov, Mariana Radev, whose bulges are just squally. Altogether, this is a fine end moving portrayal, never more so than in the haunting lullaby with which the work closes.

Another reason for collectors to hear this is the Kochubey of Boris Christoff. The great Bulgarian bass was an Italian by adoption and much loved in Italy. For Italian opera houses and RAI he studied a long series of major Russian roles in Italian translation. Of course, one would like to hear him sing the role in Russian, but if you want to hear him sing the part – and what admirer of Russian opera would not? – there is only this, so far as I can make out. His unmistakable tones carry great authority, but his phrasing is also detailed and compassionate. Great singing.

A further reason, maybe, is the Andrei of David Poleri (1921-1967). In spite of his name, Poleri was American and is mainly remembered for his contribution to Charles Munch’s Boston recordings of Beethoven’s 9th Symphony and Berlioz’s “La Damnation de Faust”. His career was brought short by a helicopter accident. He has a strong, even and ringing voice. This is not really a tenor’s opera, but he makes a good effect with his one important solo, at the beginning of Act 3.

Bastianini is a better documented singer, of course. He was never a particularly expressive artist, but he pours plenty of well-focussed tone into a role that by its nature can hardly engage our sympathy.

Which brings us to Perlea himself. He brings a fluid, conversational touch to the earlier scenes, and produces admirable vitality in the battle prelude to Act 3. He is fully participant in all the more dramatic moments. The orchestra plays well, but in a manner that sounds old-fashioned even compared with the RAI orchestras in the early 1950s, with a lot of string portamenti and a singing attack even in forte passages. The brass vibrato yields nothing to that of Russian orchestras of the same period. It is perfectly possible, of course, that this conserves a playing style that Tchaikovsky himself would have recognized. The chorus is sometimes a bit ragged, but the production evidently requires them to do quite a lot of dancing as well as singing – they seem to be wearing wooden clogs at one point.

A less prestigious venue, internationally speaking, the Festival Senese at Perugia, saw the Italian première of Tchaikovsky’s The Maid of Orleans on 30 September 1956. This was sung by Marcella Pobbe (Joan), David Poleri (King Charles), Ugo Benelli (Cardinal), Gianpiero Malaspina (Dunois), Enzo Mascherini (LJonel), Fernando Corena (Thibaut), Isidoro Antonioli (Raymond) and Belen Amparan (Agnes).

Theoretically, the recording is not much worse than that of Mazeppa, but in practice, the dividing line between something one can still listen to with a degree of pleasure, and something one will put up with only for the sake of hearing something very rare, seems to fall midway between these two recordings. Maybe, too, the dividing line between singing so individual one will make any reasonable sonic sacrifice, and singing that would be enjoyable enough if such allowances didn’t have to be made, falls midway between Olivero and Christoff, on the one hand, and Pobbe, Corena et al on the other. Indeed, I can trace no issue of this performance, whether on LP or CD. It can be found on YouTube.

On the whole, the Perugia public got a good introduction to the opera. Marcella Pobbe has a vibrant voice and is thoroughly in the part. Occasional intonation problems are countered by many more moments of gleaming security and she has a believably Slavonic sound, even though she is singing in Italian. Poleri can be enjoyed again, as can Corena and, indeed, most of the cast, though Pobbe is not alone in having the occasional intonation problem. The name of Ugo Benelli is to be approached with caution. The Cardinal is a bass role. The celebrated tenore di grazia Ugo Benelli made his debut in Montevideo two years after the present performance and I find no suggestion that he had previously trained as a bass. Assuming the name is correct, therefore, I presume this is another singer of the same name, though I can find no other mention of an Ugo Benelli who sang bass.

The orchestra is decidedly inferior to that of the Florence Maggio Musicale but Perlea conducts with a fiery passion and a dose of what one would call slancio if this were Verdi. Rather more problematic, though, is the question of what he is actually conducting. I must confess, at this point, that, to hear Mazeppa, I found an Italian libretto on Internet and followed with this – though the translation sung was a different one – rather than a score. I got the impression that a few cuts were made but I did not investigate more fully. In the case of The Maid of Orleans, I found no libretto in a language I know and so downloaded the full score (in Russian and German) from IMSLP. Alarm bells started ringing when Tchaikovsky’s quite developed and dramatic prelude had a cut of 150 bars in the middle, reducing it to a mere 41 bars. The long flute cadenza at the end also went missing. The singing and dancing at the beginning of Act 2 is confined to just one song. But all through, following the score became a sort of obstacle race as snips and slashes, with occasional bits of rewriting to cover the patches, came thick and fast. Tchaikovsky’s operas are not my musicological patch but I do know that Tchaikovsky himself was asked, for the first performance, to recast the leading role for a mezzo-soprano and to make cuts. In 1882 he made a new version, reinstating the cuts. Both the full score and the vocal scores downloadable from IMSLP are of the 1882 revision, always supposing that the cut version of the first performance was published at all. If Perlea is making the cuts sanctioned by Tchaikovsky for the first performance, he nevertheless grafts them onto a version with a soprano heroine so, to a greater or lesser extent, what we hear is a “Perlea version” of the score. It lasts about half an hour less than the recording under Rozhdestvensky. Quite frankly, I am a little surprised the difference is not greater still – assuming Rozhdestvensky himself plays the score complete.

To modern ways of thinking this is pretty shocking. On the other hand, just to play the devil’s advocate for a moment, the usual complaint is that the opera is dramatically flawed and ineffective in the theatre. So far as I can tell by listening only, Perlea’s version is taut and dramatically well-shaped. So why insist on philological purity and then complain that the opera is no good?

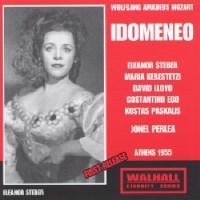

Idomeneo in Greece

Belonging to this period in Europe is a production of Mozart’s Idomeneo given on 17 September 1955 at the Herod Atticus Theatre of Athens. The cast were Constantino Ego (Idomeneo), David Lloyd (Idamante), Kostas Paskalis (Arbace), Eleanor Steber (Ilia), Maria Kerestedji (Elettra) and Petros Hoidas (La Voce). Perlea conducted the Athens State Symphony Orchestra. This was issued in 2006 by Walhall (WLCD 0166).

Belonging to this period in Europe is a production of Mozart’s Idomeneo given on 17 September 1955 at the Herod Atticus Theatre of Athens. The cast were Constantino Ego (Idomeneo), David Lloyd (Idamante), Kostas Paskalis (Arbace), Eleanor Steber (Ilia), Maria Kerestedji (Elettra) and Petros Hoidas (La Voce). Perlea conducted the Athens State Symphony Orchestra. This was issued in 2006 by Walhall (WLCD 0166).

Back in 1955, Idomeneo was sufficiently little-known for the larger part of the Athens audience to have been blissfully unaware that they were hearing a very odd version of it. We will not say too much about the tenor Idamante, since this continued to be normal till some time later – though it must be said that the first studio recording of all, the 1950 Haydn Society issue under Zallinger, used a soprano. From a romantic standpoint one can even see the logic of a baritone Idomeneo, though the logic is not Mozart’s. One might even forgive the odd snip – after all, the Glyndebourne version under Pritchard, the first “complete” version to have wide circulation, sounds more like extended extracts today. If only it were the odd snip … If only, indeed, they were big snips, but following the order of the music in the score. This, at least, is what happens in the first act and the last part of the third. In the second act and most of the third, one can only conclude that Perlea had an unbound score with the pages unnumbered, which got scattered by the famous Greek winds, leaving him to re-assemble it as best he could. Numbers are not just shuffled around within the acts, they drift back and forth between acts 2 and 3.

Always supposing one does not reject such a practice out of hand – and some might – I daresay the very worst person to assess the validity of what Perlea has done is a musician-listener with a score in front of him. Time after time, I had to stop the music and leaf backwards and forwards in the score to find where on earth they’d got to now. In truth, only the people who followed the performance in the theatre more than 60 years ago are in any position to say whether a theatrically viable experience was on offer. Failing that, I would need to do a scissors and paste job on my score, or at least on my libretto, to make it match what I am hearing. I’m not convinced that the performance would repay the very considerable effort needed to do this.

The principal justification for listening to the production today is Eleanor Steber. This is grand, secure and passionate singing. Occasionally it seems more on a Verdian than a Mozartian scale, but this is big Mozart and it’s no use selling it short. A magnificent assumption, then, and there is no other record of Steber in this role so far as I can see.

For the rest, Lloyd and Hoidas are unattractive, the others middling-decent.

Up to a point, in spite of his peculiar editorial decisions, Perlea is the other reason for hearing this performance. The Athens orchestra is a motley crew, but Perlea conveys a good deal of energy, grandeur and expressive warmth. He proves that he would have been capable of giving a notable interpretation of the score as Mozart wrote it, or would he have insisted on his strange “Perlea edition” under whatever circumstances? As it is, this is a curiosity for Steber fans and for Perlea fans prepared for rapture and frustration in equal measure.

America: The Metropolitan

It seemed logical to continue the story of Perlea’s Italian career, but in fact it developed in parallel with another that eventually came to predominate. Just as La Scala closed its doors, Perlea was summoned by the one American opera house of comparable international fame – the Metropolitan. During the 1949-1950 season, he conducted Tristan und Isolde, Rigoletto, La Traviata and Carmen. I leave Gunther Schuller to tell the tale:

One of that season’s happiest encounters for me — and I think for most of the orchestra — was the arrival of Jonel Perlea, one of the best conductors to grace the Met’s podium during my years there …

In his very first rehearsal [of “Tristan”] we could tell that we were in the hands of a superior musician. … He managed to bring to that ecstasy- and hysteria-laden score a wonderful calming restraint. With Fritz Stiedry the more frantic episodes in Tristan, especially in the third act, could easily spin out of control. It is incredibly intense music, sometimes more intense than it can readily tolerate. Perlea treated the music with an almost chamber music transparency — lyric, eloquent, even elegant — without diluting the drama and emotional excitement of Tristan, or for that matter of Carmen or any of the operas Perlea was given. … We really loved this man (4).

Some of the elderly Schuller’s memories may have become a little confused, however. He suggests that, even in 1949-50, Perlea was forced to conduct with his left hand only as the result of a stroke. This didn’t happen until 1959. He is also confusing on the reasons for Perlea leaving the Met after a single season.

All year long we kept hearing backstage rumors that certain conductors, especially Alberto Erede, also new at the Met in 1949, were agitating with the management to have Perlea retired. If true, it was but another typical example of what is known far and wide in the music world as “opera intrigue.”

Actually, Erede came to the Met for the 1950-1951 season, and was called because Perlea had virtually marched out. The issue was the operas the Rudolf Bing was willing to assign to him. It would appear that the likes of Traviata or Rigoletto weren’t good enough for Perlea, who wanted the heavier stuff like Wagner and late Verdi. But, although Perlea had somehow got to conduct that acclaimed Tristan, the heavy stuff at the Met in those years belonged to Fritz Stiedry, and there was no getting round that. Bing was only too happy to give Perlea the “lesser” Verdi, the Puccini and Mascagni, and so on, but Perlea refused it. This is where Bing remembered Erede, whose work he had admired at Glyndebourne, and called him in to fill the gap Perlea had created. Erede may or may not have been the Macchiavellian schemer Schuller believed he was, but he was not the villain in this particular piece. Rather, Perlea had chosen to cut off his nose to spite his face. During his one season he had conducted Traviata at the Met with Albanese, Di Stefano and Warren, Rigoletto with Berger, Di Stefano and Warren, and Carmen with Risë Stevens, so why not take Bing’s crumbs gratefully and reflect that Stiedry was not blessed with eternal life? And what conductor today would not sell his birthright to conduct Traviata or Rigoletto at the Met with casts half as good as those?

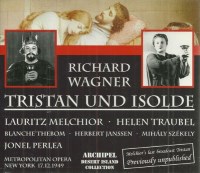

Perlea’s Met debut, in Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde, took place on 1 December 1949. It was taken to Philadelphia on 6 December and repeated at the Met on 17 December and 2 January. The 17 December performance was broadcast and has recently surfaced on Archipel ARPCD 0183-3. The full cast was Lauritz Melchior (Tristan), Helen Traubel (Isolde), Blanche Thebom (Brangäne), Mihály Székely (Marke), Herbert Janssen (Kurwenal), Emery Darcy (Melot), Peter Klein (Hirt), Philip Kinsman (Steuerman) and Leslie Chabay (Stimme eines jungen Seemanns). The variable sounds suggests that two sources, each with its attendant problems, have been used.

Perlea’s Met debut, in Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde, took place on 1 December 1949. It was taken to Philadelphia on 6 December and repeated at the Met on 17 December and 2 January. The 17 December performance was broadcast and has recently surfaced on Archipel ARPCD 0183-3. The full cast was Lauritz Melchior (Tristan), Helen Traubel (Isolde), Blanche Thebom (Brangäne), Mihály Székely (Marke), Herbert Janssen (Kurwenal), Emery Darcy (Melot), Peter Klein (Hirt), Philip Kinsman (Steuerman) and Leslie Chabay (Stimme eines jungen Seemanns). The variable sounds suggests that two sources, each with its attendant problems, have been used.

Having duly listened to these records, I find myself in the slightly embarrassing position that I really cannot think of better words to describe Perlea’s conducting than those of Schüller. In certain respects it seems a very modern concept, anticipating Boulez’s Wagnerian manner in its coolly analytical approach. But, whereas Boulez could sometimes throw the baby out with the bathwater, with Perlea, it is a case of “less is more”. For sheer riveting tension this performance can match practically anything, except maybe Furtwängler. Regrettably, the notorious “Bodanzky cuts”, removing large slices of Acts 2 and 3, were still operating at the Met. Given Perlea’s track record as a cutter, it would be risky to suppose he disagreed with them.

Melchior had first sung Tristan at the Met in 1929 and this run of performances was his last. Twenty years of singing roles like that is heavy going. Nonetheless, his voice rings out strongly and steadily in the upper register and above mezzo forte, especially in Act 2 – Act 3 shows some strain here and there. Even ten years earlier, critics were noting that his softer notes in the lower register could sound foggy. No doubt the recording has exaggerated this defect, but as presented here he sounds downright croaky, at the beginning of the Love Duet for example. Herbert Janssen is a magnificent Kurwenal, so this is one of those Tristans where the Kurwenal is better than the Tristan.

Blanche Thebom is a splendid Brangäne, but this is not one of those Tristans where the Brangäne upstages her mistress, for Helen Traubel is a gleamingly secure, fully involved Isolde. Székely is an unimposing Marke and the smaller parts are not particularly well taken.

Perlea’s Met performances of Carmen and Rigoletto – but not Traviata – were also broadcast, so may still survive somewhere.

America: San Francisco, San Antonio, Connecticut, Manhattan

The Met was followed by a season (1950) at San Francisco Opera and then a season (1951) at the San Antonio Grand Opera Festival in Texas. Perlea seems to have found it difficult to carve out a permanent niche for himself on the American operatic season.

With purely orchestral work he did better. He still enjoyed Toscanini’s support and this gained him several engagements with the NBC Symphony Orchestra. Some reports say that Perlea’s appointment to the Connecticut Symphony Orchestra was at Toscanini’s suggestion, but the site of the Greater Bridgeport Symphony, as it was later renamed, tells a different story.

The Connecticut Symphony's 10th anniversary concert at the Klein in 1955, also featured the debut of the orchestra's Music Director, Jonel Perlea, a widely known Romanian, who made his American debut at the Metropolitan Opera in 1949. Mr. Perlea came to Bridgeport because of an unusual sequence of events beginning in 1952. That year a conductor backed out of a contract over a disagreement about program selections. Another Maestro was substituted at the last minute. Elizabeth Hughes [Program Chairman] complained to her friend, impresario Arthur Judson, that she didn't want to be left without a conductor after an agreement with his office and the Symphony had been signed, and off-handedly asked if Perlea was available for the following summer. She had recently met him at a party in New York. The following July, Perlea gave up two weeks of his European schedule to be at the Fairfield campus for a single appearance. Two years later he accepted the Symphony's offer to be its Music Director (5).

Perlea remained with the Connecticut Symphony till 1965. So far as I can make out, the Connecticut Symphony didn’t make records and I have seen no objective analysis of what Perlea did or did not achieve in those years – repertoire, orchestral standards and so on. What is clear from the Greater Bridgeport Symphony site is that his tenure did nothing to ease the orchestra’s financial problems. Officially, his contract was not renewed in 1965 because the Connecticut Symphony as such ceased to operate. It was revamped under its new name, the Greater Bridgeport Symphony. Initially, as an expense-saving exercise, it worked only with guest conductors, till matinée idol José Iturbi was appointed in 1967, tweaking the orchestra’s image in a more popular direction to good economic effect.

Unofficially, though, there was some reason to suppose that Perlea was no longer the man to revitalize the orchestra’s image. In 1957 he suffered a heart attack while conducting, followed by a stroke in early 1959 – different accounts give different dates, I will come to this later. The right side of his body remained paralyzed, but he reinvented himself as a left-hand only conductor and resumed work in late 1960. He remained active for almost another decade, but it would not be entirely surprising if some Connecticut board members felt that their Music Director was living on borrowed time.

Perlea’s other long-standing American appointment was with the Manhattan School of Music, where he trained the student orchestra, apparently to a very high standard, and taught conducting. Various testimonies to his work in Manhattan can be found. A cellist, Evangeline Benedetti recalls:

Manhattan School had a good orchestra then, with a conductor who’s not well known — a masterful conductor, Jonel Perlea — who worked the orchestra unbelievably hard. So I’d had that discipline, and then auditioned for Stokowski and was accepted (6).

As usual, different accounts give different dates. Manhattan School’s own site has a photo of Perlea taken in 1952 at a reception given shortly after his appointment. This would seem to settle the date conclusively (7). He withdrew in 1959 following his stroke but was then reinstated and remained in harness till his death.

The 1950s – recordings in Europe

Perlea would have remained an elusive figure indeed had he not been booked extensively as a recording artist during the 1950s. All three companies concerned – Remington, Vox and RCA – were American but all the recordings were made, probably for economic reasons, in Europe.

Remington

The history of the Remington label is documented in detail at the

Remington site(8). Many of their recordings were made with the Berlin

RIAS Symphony orchestra – their recordings with Anatole Fistoulari

have already been mentioned in this series of articles. Perlea’s

recordings, made from 1953 to 1955, were:

Debussy: La boîte à joujoux, Berlin RIAS SO (R-199-159)

Saint-Saëns: Le Carnival des Animaux/Tchaikovsky: Swan Lake (excerpts), Berlin RIAS SO (R-199-160)

Brahms: Piano Concerto no.2, Edward Kilenyi (piano), Berlin RIAS SO (R-199-164)

Liszt: Piano Concerto no.1/Totentanz, Edward Kilenyi (piano), Berlin RIAS SO (R-199-166)

Ulysses Kay: Concerto for Orchestra, Teatro La Fenice Orchestra, Venice (R-199-173)

Dane Rudhyar: Sinfonietta/Peggy Glanville-Hicks: Gymnopedies, Berlin RIAS SO (R-199-188)

Donizetti: Lucia di Lammeroor (R-199-200/3) (details below)

I’ve been able to hear most of these.

Those who claim that Debussy’s La Boite à Joujoux is Perlea’s greatest single recording have a point. The music itself is normally thought to need special pleading – it doesn’t sound so here. For once, Perlea has a really fine orchestra to work with. As a result, he hones in on the weight, timbre and character of each phrase and episode with Boulez-like precision, revealing the work as one of extraordinary originality and modernity.

Those who claim that Debussy’s La Boite à Joujoux is Perlea’s greatest single recording have a point. The music itself is normally thought to need special pleading – it doesn’t sound so here. For once, Perlea has a really fine orchestra to work with. As a result, he hones in on the weight, timbre and character of each phrase and episode with Boulez-like precision, revealing the work as one of extraordinary originality and modernity.

Perlea is in particularly fiery form in the first movement of Brahms’s Second piano Concerto – the orchestra really bursts in after the preliminaries. The sound is lean but with ample Brahmsian phrasing. The American pianist Edward Kilenyi gives a strong, clear account, with less pedal than we often hear. It’s a forward-moving, naturally musical performance.

Hopes that this will be an outstanding dark horse on the lines of Mrazek/Swarowsky or Jenner/Dixon – both discussed in this “Forgotten Artists” series – are not wholly realized. The second movement is slowish, though slower tempi have been brought off successfully. There is a shortage of bite from both parties, Kilenyi is sometimes mannered in his phrasing and the music takes wing only in its later stages.

Hopes that this will be an outstanding dark horse on the lines of Mrazek/Swarowsky or Jenner/Dixon – both discussed in this “Forgotten Artists” series – are not wholly realized. The second movement is slowish, though slower tempi have been brought off successfully. There is a shortage of bite from both parties, Kilenyi is sometimes mannered in his phrasing and the music takes wing only in its later stages.

The third movement is kept on the move. The impression is that Perlea is trying to bring off as musically as possible a tempo he would not have chosen himself. It sounds uneasy and Kilenyi tends to move forward even so, suggesting he would rather be playing Rachmaninov. A telling moment occurs after the central climax. Perlea brings in the orchestra at a noticeably slower tempo, creating a mood of hushed mystery. Kilenyi responds to this and the whole passage is beautifully done. Then, with the re-entry of the solo cello, the faster original tempo is resumed, as I suppose it had to be, and the mood is lost.

The last movement starts blandly. Not a matter of tempo but of getting bite and snap into the dotted rhythms – this comes here and there from Perlea. Certain changes of tempo suggest they had different ideas about the music and not enough rehearsal time to sort them out.

Liszt’s First Piano Concerto (I haven’t heard Totentanz) is much more satisfactory. The first section of the Concerto had me thinking that Kilenyi might be too wayward and, at the same time, too peremptory to engage the listener’s feelings. In the slow second section a real poet emerges. Most remarkable is the scherzo section. The tempo is sufficiently slow for every single note to be heard, yet played with such precision, lightness and evenness as to sound truly dazzling. From there to the end the performance blazes and thrills. Perlea is a highly positive partner, even slightly upstaging Kilenyi in the first part before the pianist has fully warmed to his task.

Ulysses Kay (1917-1995) was an Afro-American and the nephew of a jazz musician. After receiving encouragement from fellow-Afro-American William Grant Still, he studied with Howard Hanson and Bernard Rogers at the Eastman School and then spent a year (1941-2) working with Hindemith at Yale. He studied in Rome from 1949 to 1953, which perhaps explains why an Italian orchestra was playing his Concerto for Orchestra, which he brought to Italy with him, having written it in 1948.

Ulysses Kay (1917-1995) was an Afro-American and the nephew of a jazz musician. After receiving encouragement from fellow-Afro-American William Grant Still, he studied with Howard Hanson and Bernard Rogers at the Eastman School and then spent a year (1941-2) working with Hindemith at Yale. He studied in Rome from 1949 to 1953, which perhaps explains why an Italian orchestra was playing his Concerto for Orchestra, which he brought to Italy with him, having written it in 1948.

I must say I looked up Kay’s biography only after listening, but “neo-classical” and “late Hindemith” were the labels that immediately came to mind. It is surprisingly unshowy for a Concerto for Orchestra, ending with a mostly slow Passacaglia. Did Kay feel over-conscious of the need to prove that an Afro-American can write serious music?

It’s a well-wrought work with a spacious “Arioso” second movement and a feeling of nobility both here and in the Passacaglia. Perlea builds it up well and obtains considerable dynamic shading from the orchestra. A certain Italianate quality to the orchestral sound, particularly the trumpet vibrato, had me thinking of Casella as much as of Hindemith – though Casella’s own Concerto for Orchestra is a punchier affair. I will not avoid other works by Kay if they come my way, but I’m not stimulated to seek them out at all costs.

Dane Rudhyar (1895-1985) was born in Paris as Daniel Chennevière. In 1916 he came to New York for a performance of one of his works and remained in the USA, becoming an American citizen in 1926. He was drawn into the worlds of astrology and theosophy, about which he wrote copiously. He also wrote novels and painted. As a composer, he associated with those like Ruggles and Cowell who were more for throwing brickbats at the system than for setting up rigorous alternative systems of their own. An off-beat figure for most of his life, he was rediscovered as a New Age guru in the 1970s.

In line with his theosophical beliefs, Rudhyar believed that the “new composer was no longer a ‘composer’ but a “medium, an evoker, a magician” (9). The danger with this sort of thing is that unreasonable expectations may be aroused. We might remember how Cyril Scott, another exponent of the esoteric, published a piano suite in 1913 called Egypt, supposedly inspired by memories of “my past Egyptian lives”. Stylistically, it is no different from his other music written at the same time.

Rudhyar’s Sinfonietta was reshaped in 1928, according to the site dedicated to his work, from a Sonatina for piano (10). A drastic reworking surely, since only the quiet third section sounds as if it could be effective on the piano as it stands. It was revised in 1979, but Perlea obviously played the first version. Oddly enough, Rudhyar’s reliance on short, gritty motives, deliberate avoidance of logical continuity and an alternation between quiet meandering and colossal climaxes – the conclusion is awe-inspiring – reminded me of Havergal Brian as much as anyone. Another musical outsider, but one whose standpoint could not have been more different. Perlea conducts with power and conviction, the early vinyl sometimes buckles under the strain.

Perea’s earliest “official” opera recording was his only one for Remington – Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor. The cast consisted of Renata Ferrari-Ongaro (Lucia), Giancinto Prandelli (Edgardo), Philip (Filippo) Maero (Enrico), Norman Scott (Raimondo), Luigi Pontiggia (Arturo), Tosca Di Leo (Alisa) and Uberto Scaglione (Normanno). The orchestra and chorus were those of the Teatro La Fenice, Venice.

Operadis gives the date of this performance as 15 March 1951, which

does not tally with the statement by the Remington

Site that Perlea recorded for Remington from 1953 to 1955. The “Sound

Fountain” is definitely wrong in describing it as a live performance.

Operadis gives it as a studio recording and it quite clearly is so.

Listening on headphones reveals no trace of audience rustle. It would

also have been impossible in Italy, in those days, for a tenor to sing

his major arias even half as well as Giacinto Prandelli does without

roars of applause breaking in before the orchestra has finished. Furthermore,

the precision and fine intonation of the horn chording at various points

would have been difficult to achieve live with a much finer orchestra

than this. One further oddity: on some issues, the conductor was described

as Laszlo Halasz, who acted as producer for Remington and certainly

conducted some of their recordings. The general view is that Perlea

was the conductor.

Back to him shortly. The heart of this opera, the justification for doing it, is Lucia. You won’t find many references to Renata Ferrari-Ongaro. For Remington, she sang Liù in a “Turandot” made at about the same time under Capuana. As just Renata Ongaro, there’s a live “L’Italiana in Algeri” from 1960, also under Capuana, and she sang in Ghedini’s “La Pulce d’Oro” under Abbado at the Teatro Comunale of Florence in 1963. As a teacher, she is listed in a good many singers’ curriculums.

On this showing, she has a very nice voice, pure, steady and virginal, inherently suited to Lucia. It is a very even voice throughout the register, remaining beautiful even on the unscripted top Es. She is technically well prepared, unfazed by the agility of the traditional cadenzas. So far, so very nice. Unfortunately, I don’t think I’ve ever heard a singer so emotionally inert. It really does not seem to have occurred to her that there is anything more to the music than pretty pattern-making. In her first scene, she us upstaged expressively by the Alisa. In the closing duet of Act 1, in the famous chromatic theme Prandelli shows her time and again how, without exaggeration and tricks, just a few subtle inflections and a bit of colouring, this music can come to life. But all to no avail. She goes her placid way. I realize this is pre-Callas, pre-Sutherland, at least in concept. But, well before this, Lina Pagliughi had shown that a light, agile voice, such as Donizetti probably had in mind, can perfectly well express emotion too.

Could Perlea have done something about it? Well, in a low budget production like this, we just don’t know how much time he had to work with the singers. He begins well, with a fine appreciation of the orchestral timbres. There is plenty of energy, but also plenty of atmosphere. He seems to want to relate Donizetti back to Cherubini rather than forward to Verdi. This in itself is no bad thing, and there are passages in Lucia’s faster music where the conductor seems to be trying to push the soprano on – but the lady’s not for pushing. By the end, the prima donna’s apathy impregnates the whole enterprise. After her very sane mad scene has dragged to its end, one welcomes the arrival of Prandelli, anticipating that from here to the end, at least, the performance will be worth hearing. He certainly does raise the temperature, but the suspicion is that Perlea himself has given up by then. He accompanies precisely and correctly but without apparent involvement. I was reminded of certain performances under Erich Leinsdorf where everyone seems on tenterhooks to get everything right, while missing out on the one thing that matters.

In truth, it doesn’t help that Perlea’s orchestra is very backwardly recorded. The voices are clear, but when two or more of them are singing, I struggled to grasp the harmonic structure of the music, even with the score in front of me.

A set for Prandelli admirers, then. The other singers are mainly good, and Norman Scott, as Raimondo, has a finely resonant timbre. Only the Arturo is woodenly inexpressive, suggesting that he might actually have been the right match for this particular Lucia.

Vox