I. Setting the Scene

|

Reyer, 1907

Source: hberlioz.com |

When Ernest Reyer died in 1909 a contemporary wrote that Reyer could descend into eternal rest with the knowledge that his name would not perish, because he had left behind him, as guardians of his memory, the two immortal figures of Sigurd and Salammbô. More than a century later, that immortality has vanished.

None of his five operas are in the standard repertoire.

Sigurd, rarely performed, is remembered as a French copy of Wagner’s

Ring.

Salammbô has been produced only once since the 1940s, and then in an abridged version.

Reyer is not immortal; he is not even a demi-god. His works have descended into Hades, and there his ghost wanders among the dismal shades.

That said, Reyer’s works contain much that is beautiful and much that is impressive.

Sigurd and

Salammbô held the stage for decades; and another opera, never recorded, may be a lost masterpiece, as good as Gounod’s

Faust.

Reyer’s contemporaries saw him as a serious, innovative composer who, like his models Berlioz and Wagner, followed his own path without courting public favour.

‘He had invention,’ said Théophile Gautier; ‘originality, both natural and cultivated; a ferocious hatred of the commonplace, the hackneyed, the catchphrase; a deep sense of exotic and bizarre rhythms; a rare freshness of melody; a love of his art verging on the fanatical; an enthusiasm for the beautiful which nothing could discourage; and the unshakeable resolution to never make any concession to the bad taste of the public.’

In this determination to follow his own muse, Reyer was as high-minded as his illustrious forebear Berlioz. ‘‘Success came (and again in a certain measure), without his bowing to the mob,’ wrote Hugues Imbert, ‘and, in this, he followed the example of Berlioz.’

Reyer succeeded Berlioz as musical critic for the

Journal des Débats. Its editor, the Comte de Nalèche, wrote that Reyer had all the gifts of a writer and a critic: ‘the love of perfection without belonging to any school, sincerity, enthusiasm for that which is beautiful, indignation and contempt for mediocrity’.

Like Berlioz, he was dogged by ill luck. Although he was respected as a critic, one of his operas failed in Paris, another was written years before it was finally produced, and he feared that, just as Berlioz never heard Cassandre sing in

Les Troyens, he would never hear his Sigurd. He was happier than Berlioz, however, in that success finally came, in the last decades of his life – and unhappier in that his works are forgotten.

|

Reyer opening statue of Berlioz

Source: hberlioz.com |

True, Reyer was not the equal of Berlioz but he was his artistic heir and his chosen successor. He succeeded Berlioz as a member of the Académie, and Berlioz bequeathed Reyer his Academician’s sword and coat. Berlioz’s servant Schumann kept them safe throughout the Franco-Prussian War to be given to Reyer when the moment came.

While Berlioz was alive, Reyer was the consoler of Berlioz’s sad hours and at his bedside when he was dying. He heard his last words: ‘On va donc jouer ma musique!’ (‘Now they will play my music!’) Reyer, more than any other, worked to make those last words come true. The year after Berlioz’s death, in 1870, Reyer conducted a festival at the Opéra, the house where

Benvenuto Cellini failed, and which would not stage

Les Troyens. He organised performances of

La damnation de Faust at the Concerts Populaires in 1877 and at the Concerts du Châtelet. He organised a second festival at the Hippodrome in 1879 – and slowly he convinced France of the genius of the greatest of her musical sons.

Reyer also championed the work of Richard Wagner at a time when the German genius was unpopular in France. He first heard

Tannhäuser in Wiesbaden in 1857, in the company of the writer Théophile Gautier, father of one of Wagner’s mistresses, and wrote a glowing review in the

Courrier de Paris. He heard

Lohengrin and, in London,

Meistersinger, and urged that

La Valkyrie, Lohengrin and the

Maîtres chanteurs be performed in Paris – a courageous position to take after 1870. Much as he admired Wagner’s operas, he detested the cult of Wagner. ‘I am not a rabid Wagnerian, and no more a Wagnerian

parti pris than I am a Wagnerian without knowing it.’ If Wagner were to be played in Paris, he wanted the music-dramas to be played alongside the operas of other composers he admired: Meyerbeer, ‘the greatest dramatic composer of our period’; Weber, ‘the greatest musician of the century’; Gluck, Spontini, Félicien David – and Berlioz.

II. Life and Works

|

Young Reyer

Source: hberlioz.com |

Louis Étienne Ernest Reyer was born in Marseille on 1 December 1823. Although drawn to music from an early age, his parents did not want him to become a musician. To discourage him from a musical career, they sent him at the age of 16 (1839) to Algeria where his uncle worked in the treasury. Office work did not suit him; whenever his uncle’s back was turned, the young man would read the musical score he kept concealed in a covered slip. One day, this uncle had to go away for a couple of weeks, and asked his nephew to look after his piano and his horse. When he returned, he found the piano dismantled, lying (in Adolphe Jullien’s striking phrase) like a corpse in the living-room, while the horse was an actual corpse; Reyer had heedlessly let it graze in a field of poisonous weeds.

His North African sojourn bore fruit. He wrote a mass for the arrival of the Duc d’Aumale (1847) in Algiers, and the region provided local colour and inspiration for a symphony and two operas.

Reyer returned to Paris in 1848, shortly after the Revolution that ousted the Orleans monarchy and created the Second Republic. He found Paris more congenial than Africa. He studied music with his aunt, the pianist and composer Louise Farrenc, and moved in artistic circles, where he became friends with Théophile Gautier, Baudelaire, Gérard de Nerval, Heinrich Heine, Flaubert, Méry, Félicien David – and Hector Berlioz. Many of these writers would collaborate on musical projects: Gautier and Méry wrote libretti for his music, and one of his operas was based on a Flaubert novel.

Although he wrote

Chœurs des buveurs et des assiégés (1848) and a collection of 40 harmonised ancient songs, his first work of any importance was:

Le Sélam - Symphonie orientale in 5 tableaux by Théophile Gautier (1850)

This symphony – with soprano, tenor, baritone and chorus – is a stirring, imaginative piece of music, with choruses of soldiers and shepherds, an assembly of djinns and a pilgrims’ march. Reyer had obviously put his ten years’ living in the Maghreb to good use.

Critics compared the work to Félicien David’s

Le Désert (1844), an

ode symphonie drawing on the musician’s pilgrimage to Egypt and Palestine – which, according to Adolphe Jullien, writer of an early critical biography of the composer (1909), Reyer hadn’t heard at that time.

Berlioz came to Reyer’s defence: ‘I will praise M. Reyer for showing restraint in his use of violent instruments, violent harmonies and violent modulations; his orchestral writing is gentle, dreamy, soothing and simple. I will give much higher praise to Félicien David for having had the good sense of coming first in writing

Le Désert, for had he come second, he would surely have been accused of having imitated

le Sélam!’

Jullien considered

Sélam a minor work, with some weak or frail passages – but today,

Le Sélam is one of Reyer’s easiest works to find. Reyer's symphony was recorded by Guido Maria Guida and the Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra, and is on

YouTube.

Recording

Gertrud Ottenthal, Bruno Lazaretti and Wolfgang Glashof, with the Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra conducted by Guido Maria Guida.

Les Brises d’Orient, Vol. 2, Capriccio

, C10380, recorded Berlin 1991 (

review).

Maître Wolfram - Opéra-comique in 1 act.

Libretto: Joseph Méry

First performance: Théâtre Lyrique (boulevard du temple), 20 May 1854.

Reyer’s first opera was a sentimental comedy set in Germany. Master Léopold Wolfram (baritone) and Hélène (soprano) are two young orphans brought up by an old schoolmaster, Wilhem (bass). Wilhem wants the orphans to marry. Although Wolfram is in love with Hélène, she loves the soldier Frantz (tenor). Poor Wolfram, a skilled organist, dedicates himself to music.

Reyer’s friends provided the text. Joseph Méry (later the librettist of Verdi’s

Don Carlos) wrote the libretto, while Gautier wrote Wolfram’s monologue and aria ‘Douce harmonie’ and the first two strophes of Hélène’s couplet ‘Je crois ouïr dans les bois’.

The work was encouragingly received by the critics. Both Fromental Halévy, composer of

La Juive, and Félix Clément thought it augured well for the future.

Berlioz thought the score had nothing in common with the often affected or ungainly approach of the Parisian muse. ‘What M. Reyer lacks is practice in writing, know-how, technical ease and a Prix de Rome from the Institut de France; but his melodies are natural, often moving, and there is heart and imagination in the work.’ Berlioz was particularly taken with Hélène’s couplets; her duo with Wolfram, ‘Pauvre j’avais fait un rêve’; Wolfram’s ‘delightful’ couplets ‘J’ai dit à toute la nature’, accompanied by the flute; and the two students’ choruses ‘Amis, quittons les fronts sévères’ and ‘Nous avons rossé les bourgeois’.

However, Reyer’s high-mindedness (or stubbornness) spoilt the work’s success, as Berlioz’s often had his. Told by his editor that the opera would run for at least 100 performances – if he cut the choruses – Reyer withdrew the work, choruses and all.

The work was resurrected several times, each time to Berlioz’s delight. ‘The work’s colour and sentiment are remarkable, and the pieces have a great truth of expression’

(3 September 1863). ‘The work is moving and the music remarkable by a poetry rare in our day … There is a flavour, a smell of good music which we ate and breathed with happiness.’ (24 October 1857).

It was performed in Brussels in September 1868. A duo and romance were added to a revised version at the Opéra-Comique (2e Salle Favart) in 1873, but this had only mediocre success. It was performed for the twelfth time in February 1902, with a run of 16 performances.

There are no recordings. Given Berlioz’s fondness for the opera, and the ease of producing an opera which calls for only four roles and a chorus, this is a work that an enterprising company could put on accompanied by one of Massenet or Gounod’s one act works, or which students could easily stage.

In 1857, Reyer became music critic of the

Courrier de Paris. He had already written articles for the

Revue française, Moniteur Universel and the

Gazette musicale.

Sacountalà - Ballet-pantomime in 2 acts.

Story by Théophile Gautier

First performance: Théâtre de l’Opéra, 14 July 1858.

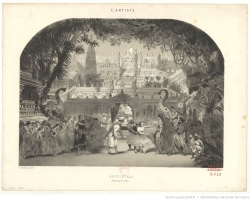

|

Sacountala – Act II décor

(click for

full-size image) |

Reyer’s next theatrical venture was a ballet adapted by Théophile Gautier from

Abhijñānashākuntala, a play by the Classical Sanskrit writer Kālidāsa (4

th century AD). Sacountalà is the daughter of a sage and a nymph; a king marries her, but another sage makes the king forget her. After many years and a journey through the Hindu paradise, the pair is reunited.

Exotic settings appealed to Reyer; two of his works are set in the Middle East, one in North Africa and another in mediaeval Scandinavia. In this, he was a man of his time. In 1789, Kālidāsa’s play was the first Indian play translated into a Western language, and inspired Goethe to write

Der Gott und die Bajadere, later turned into an opera by Auber. Schubert, Alfano and Goldmark also wrote music based on Kālidāsa’s play.

Indian ballets and operas were staples of the French stage. Today the best known are Delibes’

Lakmé (1883) and Bizet’s

Pêcheurs de perles (1863), and, at some distance, Massenet’s

Roi de Lahore (1877), but Halévy and David also wrote operas on Indian subjects.

Berlioz admired the ballet, which he found fresh and original, and not one of those conventional Parisian scores one thinks one’s heard several hundred times. ‘The harmonies are often daring, the melodies fresh and well developed. All is young and smiling, it’s green and flowering. God be praised! We’ve left the kitchen, and gone into the garden. It’s hot, but it’s the warmth of the sun; the smells are the smells of the greenery and the breeze … let us breathe.’

The work was a success, but in the end, it was only staged 24 times. With Reyer’s usual bad luck, the star ballerina Mme Ferrais left for St Petersburg, and without her, the work closed.

The ballet has not been recorded.

La statue - Opéra in 3 acts and 7 tableaux.

Libretto: Jules Barbier and Michael Carré.

First performance : Théâtre-Lyrique (boulevard du Temple), 11 April 1861.

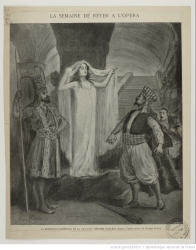

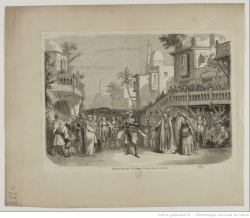

|

La Statue

Illustration de presse

(click for

full-size image) |

La statue was Reyer’s first enduring success, and earned him a knighthood of the Légion d’Honneur the next year.

The opera is set in the Middle East, like

Le Sélam, and draws on Reyer’s time living in the Maghreb. It opens with a chorus of opium smokers in a Damascus café; there are dervishes, djinns, desert storms (the simoom), and caravans of pilgrims making the hajj. Although this may sound like a rehash of the earlier symphony, critics admired the way in which Reyer came up with wholly new ideas for the score.

The story is drawn from the

1001 Nights, and had been adapted for the Paris stage in 1720. The genie Amgiad (basse chantante or baritone) saves Sélim (tenor), a young Damascene debauchee, from idleness. Disguised as a dervish, the genie promises to lead Sélim to the centre of the earth, where he will be given wealth and power. The genie leads Sélim to the ruined city of Baalbek, where the young man, half dead from fatigue and thirst, is given water by the beautiful Margyane (Falcon soprano). The two fall in love, but Sélim mistrusts his heart, turns away from the girl, and goes into the underground ruins. There, he sees twelve magnificent statues and a pedestal for a thirteenth. If Sélim marries the niece of Kaloum-Barouk, a wealthy olive merchant in Mecca, and delivers her to the King of the Genies, he will be given the thirteenth statue, which grants its owner power and happiness. Sélim goes to Mecca, and discovers that Kaloum-Barouk’s niece is Margyane, destined to marry her uncle. With the help of the genie, Sélim stops the wedding and wins Margyane. Sadly, he must surrender his beloved wife to the spirits in exchange for the treasure. In a rage, Sélim begins to smash the statues, but a figure steps onto the pedestal for the thirteenth statue. It is Margyane. All ends happily, and Sélim learns that love is a greater treasure than material wealth.

The opera was as successful as Gounod’s

Faust, and was performed for two years. Writing in 1909, Adolphe Jullien thought that if Mme Carvalho, the first Marguerite, had sung Margyane, the work would be as popular, its tunes as well-known, as Gounod’s opera. He praised its poetic charm, the grace of the melodic inspiration, the finesse and lightness of the comic scenes and the power of the dramatic ones, and the lively oriental colour of the score.

Bizet thought it the most remarkable work written in France for twenty or thirty years. Massenet, who played the timpani in the orchestra, called it a superb score. Berlioz considered Reyer an important composer, a musician in love with style, character and true expression. He thought that

La Statue, like Weber’s operas, was moving, the melody original, witty and natural, the harmony colourful, and the instrumentation energetic without brutality or violence. Johann Strauss arranged the music as a quadrille.

The numbers that most pleased the critics in the first act included the opening chorus of opium smokers; Margyane’s cantilena at the fountain, ‘Toi que n’atteint pas l’ardeur du soleil’; the duo between Margyane and Sélim; the chorus of underground spirits; and the chorus of the caravan, accompanied by flutes and a bassoon.

|

Statue – estampe

(click for

full-size image) |

Act II showed Margyane’s wedding, with choruses of musicians and neighbours. Camille Bellaigue thought it was an excellent Oriental genre painting, full of verve and colour and public life. ‘The day, the sun, and, in the streets of Arab towns, the movement, the tumult and the noise. Reyer knows them well, the mornings of Algiers and Cairo, vibrant with light and sound. As a young man, he heard the cries of the donkey-drivers pushing their beasts, the whistling of the reels laden with silk and gold, and the clinking of copper goblets which the sellers of fresh water knock against each other.’

Berlioz thought Act III was the best, and singled out the duo between Sélim and his wife and the trio with invisible choir.

The opera was performed again at the Théâtre-National de l’Opéra-Comique (2e Salle Favart) in 1868, where it ran for 60 performances. A revised version was staged at the Théâtre de l’Opéra (Palais Garnier) in 1903, but this was not a success. The stage was too big, and the singers inadequate. In this version, the comic scenes from Act II were replaced with an extended ballet.

The opera has never been recorded. Voytek Gagalka has reorchestrated the work using Virtual Studio Technology (VST) as an opera without words. This gives an idea of the work, but a work praised by three of the great French opera composers badly needs a studio recording.

Erostrate - Opéra in 2 acts and 3 tableaux.

Libretto: Emilien Pacini and Joseph Méry.

First performance: Baden Theatre, 21 August 1862, in a German translation by Josef Draxler and Ernst Paqué.

First performance in France: Opéra de Paris (salle Le Peletier), 16 October 1871.

Reyer’s next opera was also about a statue, but did not enjoy the same success in Paris.

|

|

| Athénaïs |

Scopas

|

| (click for

full-size images) |

The opera is set in ancient Ephesus (in modern Turkey). The wealthy Erostrate (basse chantante) is in love with the beautiful Athénaïs, but the richest gifts and the solicitations of her servant Rhodina (mezzo-soprano) have no effect on the courtesan’s heart. She has promised her love to the Milesian sculptor Scopas (tenor), because he will make her immortal. He has modelled a statue of Venus after her: the Venus de Milo but the city of Ephesus is devoted to the chaste goddess Diana, who cannot stand a statue of her rival goddess. Thunder roars and lightning strikes, and the Venus de Milo loses its arms. Scopas is horrified to see his work mutilated, and the furious Athénaïs demands that her lover smash the statue of Diana. Scopas refuses to commit such a sacrilege. His mistress curses him and drives him out of her presence. She turns to Erostrate, who sets fire to the temple of the goddess. The furious townspeople demand the deaths of Erostrate and Athénaïs. Scopas tries to save Athénäis, but she prefers to die in the flames with the man whose boldness won her love.

Érostrate was first performed in Baden-Baden, Germany, where the impresario Edouard Bénazet had commissioned both Reyer’s opera and Berlioz’s

Béatrice et Bénédict. Berlioz’s ‘caprice written with the point of a needle’ was performed on 6 August, and Reyer followed his master on 21 August. There, the opera was a triumph. Queen Augusta of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach, wife of Wilhelm I, awarded Reyer the Red Eagle, sending it through Meyerbeer as an intermediary. In return, Reyer dedicated the score to the queen.

The success of

Erostrate and the protection of Berlioz put Reyer in good stead in Germany – but that award and that dedication would cost Reyer dearly in Paris nine years later. Five months after the Franco-Prussian War was not the ideal time to perform an opera dedicated to the Queen of Prussia by a composer who admired the unspeakable Wagner. ‘Evidently,’ Reyer said, ‘I should have rejected the graciousness of the Queen of Prussia, and foreseen in 1862 the dreadful events of 1870.’

A cabal was organised against the opera. The soprano Julia Hisson was so incensed by the journalist Benoît Jouvin’s review for

Figaro that she struck him, and refused to appear a third time. Although Reyer could have insisted on his right to have the opera performed three times, he withdrew the work.

He seems to have accepted the failure philosophically. ‘What could save my opera from being forgotten, is that it could serve as a comparison. One could say of a boring opera that it’s nearly as boring or even more boring than

Erostrate.’

The French considered the opera monotonous – and too Wagnerian and too Berliozian. Excessive and noisy; too much importance given to the orchestration; too many recitatives disguised as couplets, duettinos and trios; and not enough developed numbers.

Others thought differently. In 1899, Marseille celebrated the 25

th centenary of its foundation with a performance of

Erostrate at the Grand Théâtre

. Adolphe Jullien, writing nearly forty years after the Paris debacle, defended the work. The first act was delicate, tender and graceful, and its orchestration evoked the memories of Ancient Greece. The second act was violent and furious, a vocal and instrumental crescendo which marvellously expressed the drama with singular power.

The opera has never been recorded.

Otherwise, Reyer was active as a critic and conductor. He organised an international festival in Baden in 1865, for which he performed Berlioz, Gounod, Litolff, Glinka, Schumann, Rossini, Meyerbeer and Liszt, and conducted for the first time the prelude and finale to Wagner’s

Tristan und Isolde. Reyer’s own contribution was

L’hymne du Rhin, with words by Méry. In 1866, he became the librarian of the Opéra and joined the

Journal des débats as music critic, succeeding Berlioz and Joseph d’Ortigue, a post he would hold until 1899. Both provided a modest but regular income. He represented the French press at the Cairo première of

Aida in 1871 and he travelled around Europe.

The Franco-Prussian War drove him out of Germany, and he had to find success in France – but, after the failure of

Erostrate, he found the doors of the Opéra closed.

For his Concerts Populaires in 1874, Jules Pasdeloup commissioned

La Madeleine au désert, a scene for bass voice with orchestra, based on a poem by Edouard Blau. At those same concerts throughout the 1870s, the Parisian public first heard extracts from Reyer’s masterpiece,

Sigurd.

In 1876, he was admitted to the Académie des Beaux-Arts, succeeding Berlioz and Félicien David but he had not established himself as an opera composer. After years of ill luck, success would come at the end of his life.

Sigurd - Opéra in 4 actes and 9 tableaux. Libretto: Camille du Locle and Alfred Blau, after the

Nibelungenlied and the

Eddas.

First performance: Théâtre Royal de la Monnaie, Brussels, 7 January 1884.

First performance in France: Lyon, 15 January 1885.

First performance in Paris: Théâtre de l’Opéra (Palais Garnier), 12 June 1885.

|

Sigurd – poster

(click for

full-size image) |

Sigurd is the work on which Reyer’s reputation, however tenuously, rests. It is one of the most impressive works to come out of late nineteenth century France. Like Wagner’s monumental tetralogy, it is based on the Norse legend of Siegfried and Brunehild, but is not influenced by the

Ring, nor are its idiom or structure particularly Wagnerian.

The idea for the opera came in the early 1860s, at a time when none of the parts of the

Ring had been performed. The librettists Blau and du Locle sketched out the idea in 1862, and Reyer and du Locle wondered whether

Sigurd could follow Verdi’s

Don Carlos (1867) at the Opéra – two years before

Das Rheingold was staged in Munich.

Although Reyer was aware that Wagner planned the

Ring, his knowledge of Wagner’s version was sketchy. He thought, for instance, that Siegfried fought the dragon underwater (conflating

Rheingold and

Siegfried).

Unlike Wagner, who set his opera in legendary times, Reyer and his librettists grounded the opera in history and minimised the supernatural elements. Much of the opera is set in the palace of Worms, and Attila the Hun courts Hilda, Gunther’s sister and the equivalent of Gutrune.

If any Wagner opera influenced

Sigurd, it is

Lohengrin, the latest Wagner opera Reyer had heard when he wrote the bulk of the opera.

Sigurd is structured in scenes rather than detachable numbers, uses recurring themes (as

La Statue had also), and emphasises the chorus, strings and brass. When he began writing, Reyer found

Tristan impenetrable. Later, he would change his mind, and Steven Huebner suggests that

Tristan was an influence on Act IV, which was only composed two months before the Brussels premiere. Otherwise, the musical idiom shows the influence of Gluck, of Weber (in the Act II ballet) and, above all, of Berlioz.

The writing is bold and imaginative. There are fine choruses: ‘Brodons des étendards’, sung by the women at the start of the opera as they prepare the hall for Gunther, or the chorus of priests in Act II, with its lovely phrase on the horns. There are arias that showcase the voice: Uta the nurse’s ‘Je savais tout! J’avais lu dans ton cœur’, where she tells Hilda that she has used her magic powers to bring Sigurd to the castle; or Sigurd’s ‘Le bruit des chants s’éteint dans la forêt immense’, recorded by Georges Thill (

YouTube); and Brunehild’s awakening ‘Salut, splendeur du jour’. Rose Caron (

YouTube), the original Brunehild, recorded ‘Des presents de Gunther’ twice, in 1902-03 and 1904, twenty years after creating the role. There are dramatic duos: the Gunther/Brunehild in Act III and the fountain duet in Act IV, as the Valkyrie breaks the enchantment on Sigurd.

|

Sigurd - scene

(click for

full-size image) |

In many ways, the opera is dramatically stronger than

Götterdämmerung. There are big ensemble scenes and spectacular stage effects: Sigurd fights with monsters, elves and kobolds, and Brunehild’s castle rises out of a lake of fire. Much of the opera is intimate, and focuses on the conflict between characters, particularly Brunehild’s relationship with her husband Gunther and his sister Hilda, her rival for Sigurd’s affections. Both Gunther and Hilda are more determined characters than Wagner’s versions; Gunther is the villain of the piece, while Hilda’s love for Sigurd sets the plot in motion.

After the failure of

Erostrate, there was little chance of a Paris production, even though the audience had heard Brunehild’s awakening and the overture at Pasdeloup’s Concerts Populaires.

Finally, Oscar Stoumon and Édouard-Fortuné Calabresi, directors of La Monnaie, offered to mount

Sigurd with Rose Caron singing Brunehild. The Brussels premiere was a success, and performances soon followed at Covent Garden (July 1884), Lyon (January 1885) and in Monte Carlo (March 1885). The Paris Opéra saw that the work was viable, and staged it in 1885. The work was again a hit.

Performances followed in New Orleans (1891) and Milan (1894). After World War I, the opera disappeared from the stages. It was last performed in Paris in 1934, but staged in Marseilles in 1963, Montpellier in 1994, Marseilles again in 1995, Geneva in 2013 and Erfurt in 2015.

The work has been recorded several times. The best is Manuel Rosenthal’s 1973 recording with a star line-up of French singers, but this, like all recordings, is heavily cut.

David LeMarrec pointed out that between half and a third of the opera was missing; I would estimate at least 150 pages. This includes not just middle sections or reprises of ensembles, but characters’ back stories and motivation (why Hilda loves Sigurd, why Brunehild was exiled from Valhalla) and dramatic moments. The second scene of Act III should open with hunters, sailors, labourers, women, soldiers and children coming to the castle for the king’s wedding. Most of this is cut; so, too, is the ballet.

Act IV is the worst affected. The prelude and women’s chorus discussing Brunehild’s unhappiness are gone. The scene in which Brunehild reveals that Odin banished her from Valhalla because she saved Sigurd – gone. A scene between Hilda and Brunehild – gone. Gunther and Hagen discuss Sigurd’s murder – gone. Hilda and Brunehild watch the murder, both torn between their desire to save Sigurd and their rivalry – gone.

Reyer would have been horrified. He detested cuts, which he described as clumsy, ruinous and anti-musical, and refused to attend performances at the Paris Opéra because cuts were made without his consent. ‘Your opera lasts a long time, but it isn’t too long,’ one of the directors of the Monnaie said to him. An opera is too long or too short, Reyer wrote, depending on whether one pays attention and on the pleasure one gets from it. Besides, the whole work, including the overture, would last four and a half hours – comparable to Wagner or Berlioz. Like those works, and those of Meyerbeer and Mussorgsky, the opera doesn’t drag; the music is impressive throughout, and the drama is engaging.

Salammbô - Opéra en 5 acts and 8 tableaux.

Libretto: Camille du Locle, after Gustave Flaubert’s novel (1862).

First performance: Théâtre Royal de la Monnaie, Brussels, 10 February 1890.

First performance in France: Théâtre Arts des Rouen, 23 November 1890.

First performance in Paris: Théâtre de l’Opéra (Palais Garnier), 16 May 1892.

Reyer’s final opera returned to the exotic climes of his early work. Salammbô is an adaptation of Flaubert’s novel of mysticism and melodrama in 3rd century BC Carthage, composed with the novelist’s blessing.

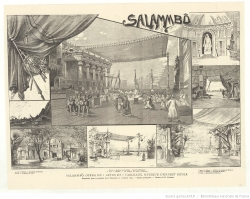

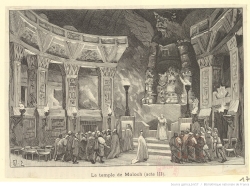

|

|

Principal scenes

(drawings by H. Cassiers) |

Act III, 2nd scene

|

|

|

| Act III – the temple of

Moloch |

Act V |

| click for

full-size images |

Salammbô (soprano) is the daughter of Hamilcar (baritone), shophet (consul) of Carthage. She quells an uprising of mercenaries led by the Libyan mercenary Mathô (tenor). Mathô steals into the temple of the goddess Tanit and steals the Zaïmph, the goddess’s mysterious veil. The loss of the veil turns the tide against Carthage, and the Council of Elders appoint Hamilcar dictator. He demands a sacrifice of twenty boys to Moloch. Meanwhile, Shahabarim (tenor), the high priest of Tanit, orders Salammbô to retrieve the veil. She goes to Mathô’s tent and seduces him to retrieve the veil, but the two really fall in love. The Carthaginians defeat the mercenaries, and Mathô is taken prisoner. He is condemned to be sacrificed to Moloch, and the crowd demands that Salammbô kill him. Since she loves him, she stabs herself instead, and Mathô, embracing her, falls on his sword.

Flaubert gave his friend Reyer exclusive rights to compose the opera, but it was not performed until 25 years after they first planned the opera. Reyer started work in 1878, but after Flaubert’s death in 1880, Reyer vowed not to resume work until

Sigurd was performed.

After the success of

Sigurd, the directors of La Monnaie mounted

Salammbô, again starring Rose Caron, whose portrayal of Brunehild had made her a star.

The work was going to be rehearsed in Paris when the authors of Massenet’s

Le mage reversed their decision to postpone its performance and reclaimed its immediate performance. ‘I could only do one thing,’ said Reyer; ‘bow and let

Le mage pass. And

Le mage passed.’

When Eugène Bertrand became the new director of the Opéra, he announced that

Salammbô would be the first opera he produced. On 16 May 1892,

Salammbô was duly put on, in a luxurious staging. The administration spent the enormous sum of 300,000 francs, which they recouped.

In Paris, the opera was performed 46 times in 1892 alone, reached its 100

th performance in 1900 and was performed for the final and 196

th time in February 1943. It was performed in the United States in New Orleans in 1900 and New York in 1901.

Jullien thought it a finer work than

Sigurd, because of its unity of style. Reyer, he wrote, created a work where each act formed a complete unit, without exactly determined divisions. This severe work, which was also Classical in its lines, impressed the public, who found none of the vocal or orchestral catteries of which they are so fond, and were conquered by the penetrating power of the music, the richness of an inspiration as fresh and passionate as if the composer were only 30.

For a modern audience, however,

Salammbô is hard to assess. There is only one, unofficial recording of a 2008 performance in Marseilles, commemorating the hundredth anniversary of Reyer’s death. That recording is heavily abridged. Entire scenes are cut. A score which calls for a large chorus is often reduced to the lead singers; what is a grand opera without ensembles? The Rosenthal

Sigurd was a studio recording, featuring many of the leading singers in France; this is a live performance, with a couple of front rank singers backed up by a solid but not world-class cast.

Like many French operas,

Salammbô was an integrated art work, meant to be seen as well as heard. The set designs give an idea of the scale of the production: enormous sets depicting temples, forums where councillors gathered under the statue of Baal, and public squares where crowds milled and thronged. Critics raved about Salammbô and Mathô’s love scene in his tent, while outside a storm rages and Carthaginians attack the mercenaries’ camp. Scenes that may have impressed onstage lose their effect on disc.

The score is more Wagnerian than

Sigurd. While one could still detect vestiges of numbers in that opera,

Salammbô, like Saint-Saëns’s operas, unfolds in a series of scenes. The musical interest is in the orchestra, more than the voice. Expressive writing for the strings alternates with heightened recit. Parts of the score are lush and languorous, others seem more conventionally late 19

th century French ideas of the exotic, without the distinctive touches Saint-Saëns or Massenet would have brought. In the work’s defence, however,

David LeMarrec suggests that Lawrence Foster’s conducting fails to bring out the poetry that is a major appeal of the work; it sounds less attractive than the score.

Unlike

Sigurd, which is heroic, masculine and mediaeval,

Salammbô is dreamy, mystical, introverted and feminine, an opera in which a woman in love with a veil wanders in North African gardens by moonlight. The finest passages are Act II, set in the temple of the goddess Tanit. Priests chant hymns to the Carthiginian gods: ‘Tanit! Rabetna! Anaitis! Astarté! Derceto! Astoreth!’ Salammbô, warned by some supernatural agency that the zaïmph, the sacred veil, is in danger, enters the shrine; there she meets Mathô, draped in the veil, and believes him to be a god. The most famous scene is Salammbô’s terrace aria, ‘Ah! qui me donnera comme à la colombe’, sung as the moon rises over the waters and the chorus rejoices in the sacrifice to Baal, which Pougin thought one of the most marvellous and moving spectacles conceivable.

|

Reyer at home, 1890

Source: Wikipedia |

While the Marseille production was a valiant effort, a staged version or a complete, studio recording is needed to reveal why this opera impressed Reyer’s contemporaries.

Recording

Kate Aldrich (Salammbô), Gilles Ragon (Mathô), Sébastien Guèze (Schahabarim), Jean-Philippe Lafont (Hamilcar), Wojtek Smilek (Narr’Havas), André Heyboer (Spendius), Murielle Oger-Tomao (Taanach), Antoine Garcin (Giscon) and Eric Martin-Bonnet (Autharite), with the Chœur et Orchestre de l’Opéra de Marseille conducted by Lawrence Foster. Opera Passion CD416700, recorded Marseille 27 September 2008.

Reyer’s final works included settings of Edouard Blau’s poems

Tristesse (1884), Gustave Boyer’s

L’homme (1892) and Camille du Locle’s

Trois sonnets. On 15 January 1909, he died in Lavandou, in the south of France.

© N. Fuller, 2016