|

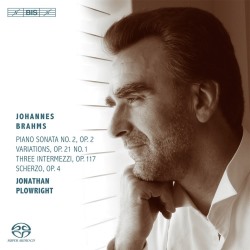

Johannes BRAHMS (1833-1897)

Piano Sonata No.2 in F sharp minor, Op.2 [28:43]

Variations on an Original Theme, Op.21 No.1 [19:57]

Three Intermezzi, Op.117 [17:55]

Scherzo in E flat minor, Op.4 [8:16]

Jonathan Plowright (piano)

rec. January 2014, Potton Hall, Suffolk, UK

BIS BIS-2117 SACD [76:24]

Well, you wait years for a single disc recording of Brahms’s early Sonata No. 2, then two superb accounts of it come along at once. Barry Douglas’s version, on volume three of his continuing Chandos survey of all the Brahms solo piano music, has impressed the critics, and seemed to me the best since Katchen and Arrau. Plowright has perhaps also embarked upon an intégrale, since this is his second solo Brahms volume for BIS.

In the Sonata No.2 Plowright is at some points more extreme in tempo than Barry Douglas, with a very swift first movement: his 5:34 the quickest since Katchen’s 5:29. No-one else comes in below six minutes and Douglas takes 6:12. Conversely Plowright’s slow movement is very slow. That andante con espressione has plenty of expression, but takes 6:56 against Douglas’s 6:19, though the expressive effect is broadly similar. Older versions have more of a true walking pace and less of a trudge - Martin Jones: 4:43, Richter: 5:12, Arrau: 5:19, Katchen: 6:00. There is a point to all this timing listing, namely that the consensus has been that the movement should have a sense of onward flow. Richter’s tempo (from a live performance), always feels just right and preferable to any of the six minute plus accounts. The rest of the sonata is superb in Plowright’s hands, and overall this can stand alongside the Douglas version as making a compelling case for this most neglected of Brahms’ large-scale piano pieces. If I prefer Douglas’s tempi for the first two movements, it must be said that Plowright’s more extreme tempi (in both directions) does give the music an exploratory Lisztian feel — very much in tune with the 1850s Zeitgeist.

There can be no quibbles about the rest of the disc. The rare Variations Op.21/1 is as satisfying as any version I know, and may even be preferable to that in the splendid complete set of all Brahms’ piano variations from Garrick Ohlsson on Hyperion. Plowright unfurls the lovely D major theme in a most ingratiating way, and compels the attention throughout the ensuing variations. The disc closes with the Scherzo Op.4, written when the composer was only 18, and his earliest piano piece to survive. It is a calling-card good enough to impress Schumann and Liszt when he took it to them. They would surely have noted its slightly mischievous, Mephisto-like quality. Certainly there is a whiff of sulphur in Plowright’s wonderfully adroit handling of its spectral elements here.

As a contrast to all this music of the young Romantic of the 1850s we also get the much loved Op.117 set of three intermezzi from 1892, when the ambitious “veiled symphonies” that Schumann heard in those large-scale early sonatas had long been succeeded by successive publications of shorter works. The piano had switched from being his means of taking on the world to, at least in Op. 117, a source of solace or intimate communion. These pieces held some personal meaning for the composer who, though hardly a personality given to confessional statements, called them “the lullaby of all my griefs”. The phrase illuminates the emotional ambiguity of the music, since a lullaby is meant to comfort, so that the grief is simultaneously expressed and assuaged. Plowright catches this mood precisely, with tempi and phrasing that draw the listener into a private world of both a nameless sorrow and its consolation.

The SACD sound is very fine, and the excellent notes by Malcolm MacDonald are much the same as those the author provided for Martin Jones’s Nimbus complete set in the early 1990s. They are still among the best of their kind, and nicely complement this excellent Brahms recital.

Roy Westbrook

|

|

|

All Nimbus reviews

All Nimbus reviews