|

|

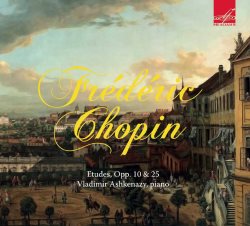

Fryderyk CHOPIN (1810-1849)

Etudes, Op. 10 (1829-32) [29:36]

Etudes, Op. 25 (1832-36) [31:41]

Vladimir Ashkenazy (piano)

rec. 1956-60, Moscow

MELODIYA MELCD1002108 [61:34]

As a pianist Ashkenazy has recorded a vast swathe of his repertoire, often multiply, for a variety of labels, in a bewildering number of locations and with a positive phalanx of recording engineers. As a result, listeners can be partisan over their favourite recording, preferring this or that version of his Prokofiev or Rachmaninov or, as here, his Chopin. In the case of the sets of Etudes most favour the 1975 Decca LP over the significantly earlier Melodiya of 1959-60. Ashkenazy was in his early twenties when he set down this earlier recording and though the famous joint-win, with John Ogdon, at the 1962 International Tchaikovsky Competition was a couple of years into the future he had already triumphed at the 1956 Queen Elizabeth Music Competition in Brussels.

It’s inevitable that this first recording should evince youthful fire but it’s also the case that’s it’s accompanied by a tempering rigorousness of mind and of execution. It appears to be the case that the pianist himself sees these early Soviet recordings as a work-in-progress, later to be supplanted by more mature and considered performances. Yet what emerges, listening objectively, is precisely that elevated marrying of technical accomplishment and intellectual control, always devoid of flashy gestures. His masculinity of approach is also accompanied by droll voicings where appropriate – such as in the A minor of Op.10 – but where poetic richness is required it’s channelled through the prism of an astute modernity. The contrary motion octaves of the E major are not tossed off as so much chaff, for example, rather here and elsewhere his warmth has a kind of hauteur about it. There is great clarity, no over-romanticism, pedalling is invariably astutely presented, and the rhythm is resilient and not subject to momentary disruptions. Vivid but controlled moments where one can detect a slightly-too-excessive rubato are rare – maybe at one or two points in the Op.25 set more than Op.10 – but there is no disputing the rigorous but dextrous control everywhere to be heard.

Whether you side with Ashkenazy’s older self in writing off these early recordings is a matter only soluble if you listen to them. If one senses a greater flexibility in that later Decca recording, and I confess that I do, it’s still hard not to be impressed by the 22-year old’s magisterial accounts of the sets in these still good-sounding recordings.

Jonathan Woolf

|

|

|

All Nimbus reviews

All Nimbus reviews