|

|

Dmitri SHOSTAKOVICH (1906-1975)

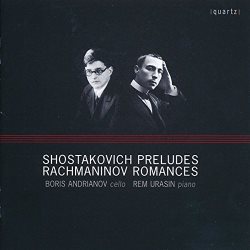

Fifteen Preludes from Op.34 for cello and piano (transcr. Rem Urashin) [23:09]

Sergei RACHMANINOV (1873-1943)

Songs transcribed for cello and piano (transcr. Rem Urashin) [27:46]

Boris Andrianov (cello)

Rem Urashin (piano)

rec. 2010, Gnessin Music College, Moscow, Russia

QUARTZ QTZ2107 [51:01]

More than most composers Shostakovich had a public and a private face in musical terms. The public face was largely influenced by the demands of the Soviet State which required music to be “at the service of the people”. This is a seemingly laudable aim but as always when states dictate such matters the aim translates into meddling and often results in stultification. Really great composers such as Shostakovich will always find a way through the exigencies placed upon them and still produce works of lasting value. A good example of that is his Fifth Symphony that despite being “a Soviet artist’s reply to just criticism” has become a firm favourite with concert audiences everywhere. The private face, on the other hand, is one that enables people under pressure to write in such a way as to remain faithful to their innermost feelings. Musically it means that they can express themselves in such a way that would be impossible otherwise, communicating thoughts and feelings that are picked up by sensitive audiences for whom the messages are all too clear. Thus one of Shostakovich’s greatest admirers, Benjamin Britten, is quoted in the accompanying notes as saying “... much as I admire the symphonies and the opera, to me Shostakovich speaks most closely and most personally in his chamber music ... when he wishes to communicate intimate thoughts to ... people unknown to him, who have souls sensitive to ... (people from all over the world, whatever race or colour). And for this one doesn’t need the mass of full chorus or orchestra and the big halls and theatre ...”.

Among Shostakovich’s most personal statements are his string quartets and his solo piano works. It is to these latter that the Russian pianist Rem Urashin turned. This disc presents his reinterpretations of a selection of the composer’s preludes from his op. 34 set which Urashin transcribed for cello and piano. Though there already exists Tsyganov’s transcriptions for violin and piano these by Urashin place the piano in a more equal role rather than that of mere accompanist. The result is a fascinating view of these brilliant pieces that enables them to be heard in an entirely new way.

In a previous Rachmaninov review I quoted his anxieties about composition: ‘I feel like a ghost wandering in a world grown alien’ adding that ‘I cannot cast out the old way of writing, and I cannot acquire the new. I have made intense efforts to feel the musical manner of today, but it will not come to me’. He was concerned that he was living at a time of change in music when, as one of what he perceived to be the last romantic composers, his music would not sit so well alongside that of his colleagues Prokofiev and Stravinsky and might fall into obscurity; he need not have worried. Aged just 20 he penned his op.4 set of six songs, three of which are represented here along with other examples he wrote over the following 22 years. Rachmaninov’s ability to portray longing was a particular strength and the songs are magnificent in that regard. With the cello as the ‘voice’ these transcriptions get to the very essence of the songs’ appeal. They seem such an absolutely obvious choice for such treatment that it is easy to forget they were ever songs. It is impossible to pick out any highlights as each is as beautiful as the last.

Winner of the first prize at the Moscow International Chopin Youth Competition in 1992, aged 15, pianist Rem Urashin is joined by cellist Boris Andianov himself a Laureate when aged 16 at the First Tchaikovsky Competition for young musicians. While not yet household names these two are a dream-team in repertoire such as this turning in performances that impress with their consummate musicianship. This is a disc that will surprise and delight in equal measure.

Steve Arloff

|

|

|