|

Support us financially by purchasing

this through MusicWeb

for £10.50 postage paid world-wide.

|

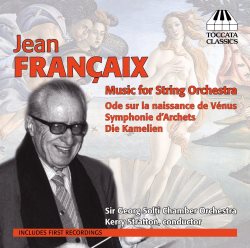

Jean FRANÇAIX (1912-1997)

Music for String Orchestra

Symphonie d'Archets (1948) [21:10]

Ode sur 'Le Naissance de Vénus' de Botticelli (1960) [5:17]

Die Kamelein (1950) [25:12]

Sir Georg Solti Chamber Orchestra, Budapest/Kerry Stratton

rec. Studio 22, Hungarian Radio, Budapest, 6-8 July 2011

TOCCATA CLASSICS TOCC0162 [52:06]

The liner for this typically fascinating and rewarding disc from Toccata Classics opens with a note from the composer's son Jacques Françaix. Amongst many interesting details, two stand out for me; the Françaix catalogue runs to around 230 works and he was one of the mostly widely performed French twentieth century composers. Yet how many general classical music enthusiasts could claim, in 2014, to have a profound knowledge of his compositional legacy?

To my mind there is a group of French composers who suffer the fate of being perceived as not as 'serious' or as revolutionary as say Debussy or Ravel but not as 'sophisticated' as Poulenc. Somewhere in this misconceived no-man's land between the two languish the likes of Françaix, Auric, Pierre Max Dubois (a personal favourite), Jolivet or even Ibert. Turning to the recorded catalogue, Françaix is hardly over-represented. Aside from various discs of chamber works, only Hyperion with three discs of orchestral music/ballets can be said to have made any concerted effort to investigate his oeuvre. Jacques Françaix points out that nearly half of his father's output involves an orchestra so even those three discs can be seen to barely scratch the surface. This makes the current disc even more welcome.

This Toccata disc focuses on works for String Orchestra. The Sir Georg Solti Chamber Orchestra has existed for just over fifteen years and comprises former students of the Liszt Academy in Budapest. Their playing strength is 6.4.4.4.2 which places it midway between the size of something like the Guildhall Strings and the string strength of a standard orchestra. With the outstanding tradition of string playing in Hungary it will come as no surprise that this is very polished and virtuosic music-making of the highest order. It’s valuable too, because it strips away many of the easy clichéd expectations one can fall into with this style of music assuming it will be "urbane", "beautifully crafted", "polished" or "witty". For sure it is all of those things but with a strong spine of formal rigour and a higher level of pungent dissonance than one might immediately expect. Given the Hungarian source perhaps it should be no surprise to hear some Bartók in the angular and muscular writing.

The disc opens with the 1948 Symphonie d'Archets. This is the only work on the disc to have been recorded before but it is my first encounter. Given the modern predilection for grand confessional statements on an epic scale this evinces a jewel-like perfection. It couples this with a certain emotional detachment that does not chime with the current zeitgeist - which makes me like it all the more. The Symphony follows the classical four movement form with the slow movement placed second. The classical inspiration even runs to having a slow introduction before the first movement proper allegro assai. Malcolm MacDonald in his expertly insightful note points out that Françaix exploits a form of thematic evolution rather than 'correct' sonata form development. Canadian conductor Kerry Stratton gets impressively athletic playing from the orchestra throughout - this does feel like large-scale chamber playing. I do have a concern with the close microphone placement with individual instruments clearly audible but that is countered by a sense of communal engagement. However, it does reduce the overall dynamic range of the playing and for all the skill on show the overall effect is rather fatiguing.

Without wishing to fall back on the clichés mentioned earlier it is true that an important part of Françaix's skill lies in elegant sophistication with which he handles his musical material and the instruments that play it. While far from easy or simple, at the same time it sounds grateful and not awkward for the simple purpose of being awkward. Melodically Françaix favours motifs rather than extended themes in part because they can be more fruitful in the way they can be developed. In a piece of absolute music such as the String Symphony that can lead towards a certain intellectual detachment meaning that ultimately one's appreciation is more cerebral than emotional. The parallel here is perhaps with the Roussel Sinfonietta for Strings (1934). That being said, the Françaix Symphony has a sly off-balance way with meter and harmony that while not making it in any way 'light' stops short of Roussel's rigorous neo-classicism. An exactly contemporaneous work is Kenneth Leighton's three movement Symphony for Strings - it makes for a fascinating comparison to hear how radically different results can spring from identical forces.

The other two works - both first recordings - have an illustrative element. The first, Ode sur 'Le Naissance de Vénus' de Botticelli was an accompaniment to a television programme about that famous picture while Die Kamelein is a ballet originally choreographed by George Balanchine. The Ode is a brief but concentrated work quite different from the bluff muscularity of the Symphony. There is a meditative-cum-contemplative quality to it that I imagine would fit its role as a perfect complement to the visuals. Again, the close proximity of the microphones diminishes the atmospheric power of the work but the playing is both elegant and controlled – a gem of a piece.

MacDonald outlines the synopsis of Die Kamelein. He describes it as a dance fantasia on some of the themes from the Dumas novel La Dame aux camélias. As reworked for the ballet this is an austere and somewhat bleak narrative matched by Françaix’s music. Even the masked ball (track 7) where the central characters meet and fall in love has a chilly nervous energy rather than joyful abandon. I do like what Françaix conjures up though; a rather queasy waltz followed in the next scene by a dead-pan siciliano where the heroine Marguerite (to quote MacDonald) “reflects that the reality of their affair was much more mundane than the legend”. Certainly there is a deliberate circumscription to the emotional range of the music – a holding in check of passion – that is both disconcerting but effective. As far as the performance is concerned, although I do not know the work at all, I wonder if Stratton is too plain and literal. For sure his approach emphasises the alienating atmosphere but I wonder if more passion should not be burning beneath the mask of indifference. The penultimate section (track 10 Im Spielsaal) I particularly enjoyed; Marguerite portrayed engaging in a series of increasingly brittle energetic dances. Aside from the narrative skill reflecting the hollow desperation of the heroine, from a technical aspect they show just how brilliantly Françaix could handle his instrumental resources. Again, a subtler hand on the podium might have been able to layer the emotions of the writing with greater skill and nuance. The delineation of primary and secondary material and how they interchange is rather lost. Likewise the return to the graveside music that opened the suite lacks the sense of final collapse and departure as the music gradually moves ever lower; quite literally into the grave. This is a very impressive work and one which deserves a wider audience.

Overall, a rewarding and stimulating disc – as with so many from this source. My concerns about the engineering and the rather literal approach to the interpretations is tempered by the pleasure in hearing the music at all. At just over fifty minutes this does feel like rather short measure – there are other string works in his catalogue. However, all three works presented here do deserve at least a foothold in the repertoire with Die Kamelien proving especially impressive.

Nick Barnard

|