|

|

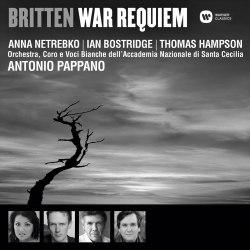

Benjamin BRITTEN (1913-1976)

War Requiem [80:05]

Anna Netrebko (soprano); Ian Bostridge (tenor); Thomas Hampson (baritone)

Coro e Voci Bianche dell'Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia, Roma/Ciro Visco

Orchestra dell'Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia, Roma/Sir Antonio Pappano

rec. 25-26, 28-29 June 2013, Sala Santa Cecilia, Auditorium Parco della Musica, Rome, Italy

Latin and English texts with English translation.

WARNER CLASSICS 6154482 [80:05]

Looking back over 2013, the centenary of Britten’s birth, I

am amazed and encouraged by the number of reissues and new recordings

of the composer’s music that have hit the marketplace. Three

new recordings of the War Requiem have been reviewed here on

MusicWeb International. These have been supplemented by two historic

recordings, one by Karel Ancerl, the Czech première from 1966(SupraphonSU

4135-2), and the first performance from Coventry Cathedral on 30 May

1962 with Britten/Meredith Davies (Testament SBT 1490). Furthermore,

my interest in this work was rekindled in November 2013, when I attended

a performance of the War Requiem at the Royal Albert Hall with

the BBC Symphony Orchestra and Chorus conducted by Semyon Bychkov.

This was the first time I’d heard it live and it was for me

one of the most memorable and moving events in my entire concert-going

experience.

It was on 14 November 1940 that the 14th Century Church

of St. Michael’s, Coventry was bombed by the German Luftwaffe.

It had only been elevated to cathedral status, on the creation of

the Coventry Diocese, in 1918. Eventually, plans were drawn up to

build a new cathedral at right angles to the ruins of the old one.

In October 1958, some three years before the estimated completion

date, the Coventry Cathedral Festival Committee approached Britten

to compose something fitting for the consecration. He was delighted

with the request and grateful to be given carte blanche to

compose anything he wished. He had for many years cherished a desire

to write a large-scale choral piece ‘à la Elgar’,

and several subjects had stirred his imagination - the tragedy of

Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and the 1948 assassination of Gandhi. These

ideas remained pipe-dreams. Now, an opportunity arose in which he

could rise to the challenge.

His decision was to compose a setting of the traditional Latin Requiem

Mass, interspersed with poems by Wilfred Owen, who was killed during

the First World War, sadly just one week before the Armistice in 1918.

True to form, and in keeping with his habit of working to tight deadlines,

Britten only started work on the Requiem in 1961. It was completed

in January 1962, barely four months before the first performance.

Thinking back to the concert last November, I truly believe this is

a work that needs to be experienced in a live performance setting

to be fully appreciated. One then gets some conception of the spatial

separation between the different groups involved. Britten composed

the work for a main orchestra, accompanying the soprano soloist and

mixed chorus in the Latin mass parts. A chamber orchestra of twelve

instrumentalists accompany the tenor and baritone soloists in the

Wilfred Owen settings. A boys choir with its own conductor, and supported

with a chamber organ is positioned distant from the main body of performers.

This spatial separation has to be apparent and audible for any recording

of this work to be successful.

The present recording was made in June 2013 in the Sala Santa Cecilia,

Auditorium Parco della Musica, Rome. Two months later, Pappano and

his forces performed the work at the Salzburg Festival to great critical

acclaim. Pappano has been musical director of the Orchestra dell'Accademia

Nazionale di Santa Cecilia since 2005. For this recording he chose

three distinguished soloists, the Russian soprano Anna Netrebko, the

American baritone Thomas Hampson and the English tenor Ian Bostridge.

Being no stranger to this work, and having many performances under

his belt, Bostridge is a very apt choice; he has this work in his

blood.

All three soloists are excellent. Anna Netrebko, like Galina Vishnevskaya,

harks back to Britten’s choice of a Russian soprano in the first

recording. With such power and force in her delivery, she projects

well. Hampson shows great sensitivity in shaping his part and imbuing

it with a formidable range of tonal colour. However, it is Ian Bostridge’s

contribution which stands out for me. I much prefer him to Peter Pears

in the Britten recording. Clarity of diction, beauty of tone, phrasing

and dynamic control all add up to a performance which is both consummate

and compelling.

The success of this recording seems to hinge on the fact that Pappano

brings all his experience and talent to the fore. Excelling in opera,

he coaxes the soloists, choir and orchestra to deliver a strongly

argued performance. The warmth of the Italians adds to the success

of the mix. The opening Requiem Aeternam beginsvery

quietly. Pappano gradually builds up the dynamic level and tension,

and there is great drama throughout. The orchestral sound is vivid

and immediate. What is evident is the conductor’s scrupulous

attention to detail and preparation.

The brass section in the Dies irae ring out with burnished

tone, and the sheer visceral energy at Tuba mirum (The trumpet,

scattering a wondrous sound) is breathtakingly shattering. The instrumentalists

that make up the chamber orchestra are terrific, and the contrast

between them and the full orchestra is palpable. The adult choir is

first class, with clarity of diction always apparent.

The choristers are excellently placed and one senses spatial separation

from the main groups. They have that distant, other-worldly and ethereal

quality. However, Britten specifically asks for boys’ voices,

favouring that particular timbre. Though the booklet does not specify

the make-up of the voices the chorister group sounds mixed to me.

A DVD

from German television of Andris Nelsons conducting a performance

with the CBSO in Coventry Cathedral 2012 uses a girls’ choir,

and it is clearly not ideal. In Helmuth Rilling’s recording,

the choristers lack the distant perspective completely and sound unimaginative

and expressionless. In fact, this entire performance generally leaves

me cold (Hänssler

Classic CD 98.507).

All told, Pappano’s is an impressive achievement, and one I

will return to often. Unfortunately, I have not had the opportunity

to listen to the McCreesh (Signum

SIGCD340) and Jansons (S&H

review of concert; CD on BR

Klassik 900120) recordings, that were also released in 2013.

The booklet notes set the context and background. Texts and translations

are provided. At 80 minutes, the work is accommodated on a single

CD, and this is an advantage. This version will provide an excellent

alternative to the composer’s own on Decca.

Stephen Greenbank

Previous reviews: John

Quinn,

Michael Cookson

Masterwork Index: War

Requiem

|

|

|