|

|

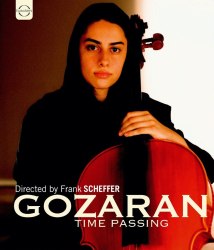

Gozaran (Time passing)

A film by Frank Sheffer (2012)

Tehran Philharmonic Orchestra and other musicians/Nader Mashayekhi

rec. Tehran, Osnabrück, Vienna, 2009

Picture format Blu-ray Disc: 1080i Full HD - 16:9

Aspect Ratio: 16:9 - 1.78:1

Sound format Blu-ray Disc: PCM Stereo, DTS-HD Master Audio 5.1

Dubbed: German, Persian

Region code: 0 (worldwide)

Subtitles: English, German, French

Booklet notes: English, German, French

EUROARTS Blu-ray 2058764 [85.00]

In order for evil to thrive, Bonhoeffer once remarked, it is only necessary for a good man to do absolutely nothing. This pessimistic outlook could perhaps be applied even more appositely to the field of ‘classical music’. It’s a genre which, at least since the beginning of the twentieth century, has been kept at a somewhat suspicious distance by most of the world’s governing classes with a mixture of arm’s-length subsidy and benign neglect. Indeed the examples of the totalitarian states which attempted to interfere in the realm of the arts - Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia the most notorious, although not the only, examples - have been far from encouraging. The sufferings of all writers under these regimes, although not to be compared with the mass exterminations of whole other classes of people, have nonetheless been severe and have seriously damaged the evolution of composers’ musical styles. It was left to Maoist China during the era of the ‘Cultural Revolution’ to go one step further, and by identifying ‘classical music’ with ‘bourgeois intellectualism’ to seek its wholesale extirpation from the scene. Composers and performers in China hunkered down beneath the ramparts as best they could, and waited in hope for better times. In due course these arrived, and now Chinese classical musicians give recitals and concerts for large and enthusiastic audiences.

When the brutal excesses of the Shah’s Iranian regime became too much even for the post-Kissinger generation in the US State Department, they connived at the return to Iran in 1979 of the Ayatollah Khomeini. They were soon to discover the truth of Hilaire Belloc’s cautionary moral: “Always keep a hold of Nurse, for fear of finding something worse.” The new Islamic fundamentalist regime in Iran set about eliminating in a wholesale fashion all western elements from their state. This extended beyond American-influenced pop music to all ‘anti-Islamic’ elements which smacked to the slightest degree of the hated ‘great Satan’; not to mention the issue of death threats against foreign authors. Before the arrival of the revolutionary government there had been some serious attempts to establish both a performing and composing tradition in Iran, but this now became stillborn. Classical music continued to be given, and the Tehran Symphony Orchestra continued to play, but the repertory had become ossified and new talent was positively discouraged.

Which is where this documentary film comes in. We are told horrifyingly that one young girl was told that she should never be able to play the trumpet, because this was an exclusively male preserve. The film follows the career of conductor and composer Nader Mashayekhi, in exile in Vienna since 1979, on his return to Tehran. Although it suggests that it covers the whole of his period in Iran, the booklet reveals a slightly more complicated story. He had originally been invited to take over as principal conductor of the Tehran Symphony Orchestra. When he attempted to programme music by such ‘advanced’ composers as John Cage, Morton Feldman and Frank Zappa, he was summarily dismissed by the officials of the Iranian Ministry for Culture and Islamic Leadership. This documentary begins as he is attempting to form a new orchestra, the Tehran Philharmonic, with the intention of performing music outside the parameters established by the Ministry.

Mind you, he clearly didn’t make things easy for himself. The central planks of the repertory for this new orchestra consisted not only of the music of composers like Cage, but also the St John Passion of Bach - a non-Islamic work if ever there was one - and the symphonies of Mahler. To perform Mahler in such a virulently anti-Zionist state as Iran seems like the equivalent of Barenboim’s espousal of Wagner in Israel with his East-West Divan Orchestra. It was clearly intended to make the same sort of political - or rather, anti-political - point that music should transcend nationality. It is perhaps therefore not so surprising that following the violently contested elections in Iran in 2009 both the conductor and his father found themselves back in exile. Following the thaw in the regime last year (2013) they might well be able to return. Mashayekhi in the closing segment of this documentary expresses his wish to do so, although I cannot find any reports of his being able to achieve that goal.

This history of frustration and failure is not all that there is to tell about this film. Towards the end we are shown musicians from the Tehran Philharmonic coming to Osnabrück in Germany to give concerts of music by Arvo Pärt, a composer who after a similar history of official ostracism and neglect has been able to emerge on the other side into the sunlit uplands. This enables the documentary to end on a note of hope as well as frustration. Producer Frank Scheffer states in his booklet note that he aimed to make a “poetic music documentary” which would “stay above politics”. That is not possible in real terms, because the politics are an implicit part of the story but he has succeeded in making a film that makes a serious philosophical point. The cinematography is very beautiful, especially the skyscapes over the Iranian desert.

The musical rewards are somewhat more of a mixed bag. It would be idle to pretend that the players of the Tehran Philharmonic are of international standard - the horns in particular are very shaky during the fourth movement of the Mahler Third Symphony - and, although this is not stated anywhere in the material, it is clear that some of the music we hear performed as background is being given by other players. One initially wondered at the excellent German singing in the performance of the St John Passion, only to find on closer examination of the booklet that the choir came from Osnabrück, and that the Iranian orchestra was ‘bolstered’ by players from there as well. That is hardly important; but one would also have liked to know who the solo singers were in the Mahler excerpts, since some of them are very good indeed.

Government interference in music can be beneficial - take the example of Venezuela - but for much of the time it is better if politicians stay well away from the arts. Composers, writers, painters, performers and other artists are driven by their own internal demons and will continue to pursue their paths irrespective of administrators and officials. All that the latter can do is to provide an atmosphere in which they can do so. It is to be hoped that the new Iranian government will now begin to relax their iron grip on the cultural development of their country. If this documentary helps to focus attention on the matter, that is well and good. At all events the basic philosophical moral of the film comes across loud and clear: that basic human decency and toleration will always survive, to triumph in the end over those who suffer from the peculiar delusion that they and they alone have a monopoly of the truth.

Paul Corfield Godfrey

|

|

|