|

|

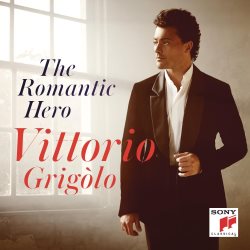

The Romantic Hero

Jules MASSENET (1842-1912)

Le Cid: Ah! tout est bien fini…Ô souverain, Ô juge, Ô pere [4.48]

Manon: Instant charmant…En fermant tes yeux* [3.44]: Je suis seul!...Ah! fuyez, douce image [5.02]

Werther: Toute mon âme…Pourquoi me reveiller [2.53]

Charles GOUNOD (1818-1893)

Faust: Quel trouble inconnu…Salut, demeure chaste et pure [5.49]

Roméo et Juliette: L’amour!...Ah! lêve-toi, soleil! [4.18]: Va! je t’ai pardonée…Nuit d’hyménée* [10.38]: C’est la! Salut! tombeau sombre [5.16]

Georges BIZET (1838-1875)

Carmen: La fleur que tu m’avais jetée [3.53]

Giacomo MEYERBEER (1791-1864)

L’Africaine: Pays merveilleux… Ô paradis [3.09]

Jacques HALÉVY (1799-1862)

La Juive: Rachel, quand du Seigneur [5.37]

Jacques OFFENBACH (1819-1880)

Les contes d’Hoffman: Et moi?... Ô Dieu! de quelle ivresse+ [2.21]

Vittorio Grigòlo (tenor), *Sonya Yoncheva (soprano), +Alessandra Martines (speaker), RAI National Symphony Orchestra/Evelino Pidò

rec. RAI Toscanini Auditorium, Turin, 6-9 June, 22-31 July 2013

SONY 88883 756582 [57.18]

Since time immemorial the relationship between Italian singers and French opera has tended to be a distinctly one-way traffic. In the nineteenth century even operas written — often by Italian composers — for the Paris Opéra were regularly given in translation when they were performed in Italy … and indeed elsewhere. This trend continues to this day with operas such as Rossini’s William Tell and Verdi’s Don Carlos. When in the 1960s French operas were being recorded in their original language, French tenors were rather thin on the ground. The recording companies had perforce to turn to tenors from the Italian school to take leading roles in Faust, Carmen and Roméo et Juliette. The results could often be less than satisfactory. John Culshaw in his autobiography Putting the record straight tells a long and hilarious story about the need to engage a French coach for Franco Corelli in the Karajan recording of Carmen; since they hired a woman for this purpose, she ran into immediate difficulties with Corelli’s justifiably jealous wife. Later tenors from the Italian school – Domingo, Pavarotti, Carreras – also made frequent expeditions into the French repertory. It was not until the advent of Roberto Alagna that a native Francophone emerged who could tackle the big roles naturally. Vittorio Grigòlo describes himself as an “Italian-French European,” and although he was raised in Rome he attended a French school. As such it is a pleasure to encounter this sort of voice singing in French, even if the choice of items on this recital is somewhat predictable.

What however is not so predictable in a recital of popular items is the degree of dramatic involvement that Grigòlo demonstrates and this is an equally pleasurable element. One immediately notices this in his exquisite mezza voce delivery of the text in the extract from Massenet’s Werther, as well as his beautifully floated high notes. These are also notable in his account of the Flower Song from Carmen, where he manages to deliver the penultimate phrase in the soft tones that Bizet requests rather than the stentorian high B flat that one so often hears. One would love to hear this singer in the high-lying aria from Bizet’s Pearl Fishers as well.

Time and again one is impressed by Grigòlo’s command of the higher reaches of his range. He can produce a solid high C — as in the aria from Gounod’s Faust — without resorting to bellowing. He can also shade with delicacy into the same notes when the composer, or the context, demands this. It is a real delight to hear Gounod and Massenet, whose operas contribute by far the most substantial part of this recital, delivered in this manner. Grigòlo’s commitment and natural good taste is also demonstrated by the fact that he places the arias in their dramatic context by giving us the recitatives that precede them (where appropriate). In his delivery of these he again shows the same exquisite sense of colouring. Sony aid and abet his efforts by giving us full texts with English translations of all the numbers. Also welcome is their willingness to furnish other artists where required, as in the expressive delivery of the spoken lines by the Muse in the Offenbach. The excellent Sonya Yoncheva contributes occasional phrases in the first Manon extract and more substantially in the duet from Roméo et Juliette. We even get the two spoken lines from the Porter in the second Manon extract, although the artist concerned is not identified.

It is perhaps a pity that the extensive extracts from Roméo et Juliette are given as three separate items during the course of the recital. This robs us of the chance to observe the dramatic development — such as it is — of the character throughout the course of the opera. One would have welcomed the opportunity to hear the two artists involved in a complete performance. That said, Yoncheva is notably less expressive than Grigòlo although by no means negligible in her willingness to sing quietly when required. The two blend well in their duet. Before the final Gounod item Grigòlo demonstrates thoroughly heroic tone in the prayer from Le Cid.

Tributes must also be paid to the expressive playing of the orchestra under Evelino Pidò. The duet for two English horns in the prelude to the aria from La Juive is beautifully phrased, only one of many delightful touches.

The playing time is somewhat stingy – the addition of further items would have been welcome – but the quality is high. To hear Grigòlo’s delivery of the final line from Eleazar’s aria in La Juive is a real treat. Is there any chance of hearing him in a really complete recording of this opera – and indeed in further and possibly more arcane reaches of the French repertoire? A singer with this evident intelligence and understanding deserves to be heard in full dramatic context.

Paul Corfield Godfrey

|

|

|