|

Support us financially by purchasing

this disc through MusicWeb

for £11 postage paid world-wide.

|

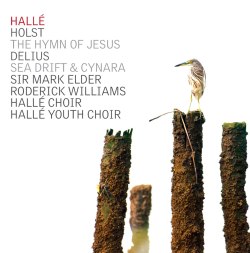

Gustav HOLST (1874-1934)

The Hymn of Jesus, op.37 [21:55]

Frederick DELIUS (1862-1934)

Sea Drift [27:01]

Cynara [11:35]

Roderick Williams (baritone)

Hallé Choir, Hallé Youth Choir

Hallé Orchestra/Sir Mark Elder

rec. live, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester, 15 March 2012, and in rehearsal (The Hymn of Jesus), 17 March 2011 and in rehearsal (Sea Drift), Studios of BBC MediaCity, Salford, 4 Feb. 2012 (Cynara)

HALLE CD HLL 7535 [62:25]

Holst’s Hymn of Jesus is a genuine masterpiece, one of his greatest works. So the question arises, why don’t we hear it more often in concert? I’ve thought about this a lot, and the truth is I believe it suffers from what can be described as ‘short work syndrome’. By this I mean that, though at 20 odd minutes, it isn’t long enough even to fill one half of a programme, it is demanding and time-consuming to prepare, making considerable demands on choir and orchestra. Holst’s work shares this unhappy status with other such fine pieces as Vaughan Williams’ Toward the Unknown Region, and Brahms’ Song of Destiny. Another factor for all these is that they do not have the attraction of a solo part to boost their profile.

So The Hymn of Jesus has become a comparative rarity, and was really in need of an outstanding recorded performance to bring it into prominence. That is what it has received here: the Hallé Choir sings with great imagination and rhythmic precision, while the orchestra colours the music superbly. Above all, Sir Mark Elder has the timing of the work to perfection, and guides his forces through with exactly the combination of mystery and momentum that characterises the piece.

The text is based on the apocryphal Acts of St. John, which postulate the heretical teaching of Gnosticism, expressed in the phrase ‘Divine grace is dancing’. Holst finds the right musical language to match the words; mystical in its use of ancient plainchants, Vexilla Regis and Pange lingua - both heard in the introduction - and powerful rhythmic drive in the exciting 5/4 section. The mention of that time-signature reminds me that this work follows immediately on from The Planets in Holst’s output, and has many characteristics in common; the irregular rhythmic patterns found in Mars, the tick-tocking ostinati of both Venus and Saturn; the remoteness of Neptune, and so forth.

I should mention too the wonderful contributions of the Hallé Youth Choir, who supply the music’s radiant halo in their ‘Amens’, as well as the first appearance of the Vexilla Regis plainsong. The main Hallé Choir are magnificent, with terrific weight and precision for the great utterances of ‘Glory to Thee’, but also a truly magical hushed pianissimo for ‘Behold in me a couch; rest on me’. At the end, the burst of applause comes as a shock - hard to believe that such an immaculate performance could be a live rather than a studio one.

Delius’ word setting is for me the least favourite aspect of his art. The inherently shape-shifting nature of his melodies and harmonies can make the vocal line seem stilted, awkward even. Nevertheless, Sea Drift is an undeniably beautiful piece, and when it is done like this, with such red-blooded passion from both the Hallé Choir and the excellent soloist, it is a powerful experience. The choir, it should be said, is not on quite such good form as for The Hymn of Jesus (recorded a year later). There are one or two ragged entries and patches of slightly suspect tuning but they completely get away with it because of the sheer sense of commitment in their singing.

Cynara is an interesting work, not often heard. It is for baritone and orchestra, and is a setting of a poem by Ernest Dowson; a love-poem, which refers to the Odes of the ancient Roman poet Horace. It shares this with Dowson’s most famous poem, whose most celebrated lines are ‘They are not long, the days of wine and roses’, as well as an aching sense of regret, which makes it perfect for Delius. His music evokes that emotion more potently than any other I know; that gives the piece its emotive force, but it’s the repetition in the words of the four stanzas that supplies a sense of structure and direction which we sometimes miss in Delius’s vocal works. The baritone Roderick Williams is simply outstanding; firm in tone, true in intonation, but sensitive to the intensity of the text.

This is an outstanding and memorable CD, bringing together three masterpieces of English music each of which is less well-known than it fully deserve to be.

Gwyn Parry-Jones

See also reviews by John Quinn and Michael Cookson

Holst discography & review index

|