|

Support

us financially by purchasing this disc from |

|

|

|

|

|

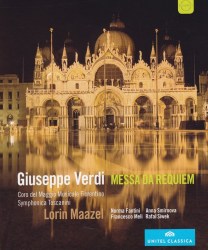

Giuseppe VERDI (1813-1901)

Messa da Requiem (1874)

Norma Fantini (soprano); Anna Smirnova (mezzo); Francesco Meli (tenor);

Rafal Siwek (bass)

Coro Del Maggio Musicale Fiorentino

Symphonica Toscanini/Lorin Maazel

rec. Basilica di San Marco, Venice, 16 November 2007

Picture format: 1080i Full HD 16:9 aspect

Sound formats: PCM Stereo, DTS-HD Master Audio

Subtitles: Latin, German, English, French

Booklet notes: English, German, French

EUROARTS 2072434

[97:00]

As the booklet essay notes, Verdi was not a religious man. Indeed,

it is fair to say he was anti-cleric and particularly anti-Pope, as

were many Italian Monarchists and Republicans. They held this view

because of the activities of holders of the Papal office over the

period of the fight for Italy’s unification and independence.

Despite those views he wrote religious music. At the death of Rossini,

an idol of Verdi’s, in November 1868, Verdi suggested that the

musicians of Italy should unite to honour their great compatriot.

This would involve them combining to write a Requiem for performance

on the anniversary of his death. No one would receive payment for

his contribution. There would be volunteers each to write one section

of the Mass being drawn by lot. After the performance, which Verdi

recognised would lack artistic unity, the score would be sealed up

in the Bologna Liceo Musico. The idea was enthusiastically received

and a committee set up to oversee the project. To Verdi, pre-eminent

among the names, fell the closing section, the Libera Me (see

review).

Verdi had his composition ready in good time despite revising La

Forza del Destino along the way. Problems arose in respect of

the chorus and orchestra, for which Verdi, somewhat unfairly, blamed

his friend the conductor Mariani and the project floundered. Verdi

met the costs incurred.

In the year of Rossini’s death, aided by arrangements connived

at by his wife and long-time friend Clarina Maffei, Verdi visited

his other Italian idol, Alessandro Manzoni. He had read Manzoni’s

novel I Promessi Sposi when aged sixteen. In his fifty-third

year he wrote to a friend, “according to me, (he) has written

not only the greatest book of our time but one of the greatest books

that ever came out of the human brain.” The novel has been

described as representing for Italians all of Scott, Dickens and Thackeray

rolled into one and suffused with the spirit of Tolstoy. It was not

merely the nature of Manzoni’s partly historical story that

gave the work this ethos, but the language. With it Manzoni made vital

steps towards a national Italian language to replace the proliferation

of dialects and foreign administrative languages present in the peninsula.

When Manzoni died in May 1873, after a fall, Verdi was devastated

to the extent he could not go to the funeral for which the shops of

Milan were closed, and the streets lined with thousands. The King

sent two Princes of the Royal Blood to carry the flanking cords. They

were aided by the Presidents of the Senate and Chamber as well as

the Ministers of Education and Foreign Affairs. A week after the funeral

Verdi went to Milan and visited the grave alone. Then, through his

publisher, Ricordi, he proposed to the Mayor of Milan that he should

write a Requiem Mass to honour Manzoni. This was to be performed

in Milan on the first anniversary of Manzoni’s death. There

would be no committee this time. Verdi proposed that he himself would

compose the entire Mass and pay the expenses of preparing and printing

the music. He would specify the church for the first performance,

choose the singers and chorus, rehearse them and conduct the premiere.

The city would pay the cost of the performance. Thereafter the Requiem

would belong to Verdi. The city accepted with alacrity. It was Verdi’s

eulogy to a great man of Italy. The work is often referred to as The

Manzoni Requiem.

This performance is intended to revere another great Italian musician,

the conductor Arturo Toscanini. It was he who had led the thousands

of Italians who lined the streets of Milan for Verdi’s funeral

in the singing of the famous chorus Va pensiero from Nabucco.

This 2007 performance of the Requiem, in the magnificent and ornate

basilica of St Mark's in Venice, was to mark the fiftieth anniversary

of Toscanini's death. The music was first performed there on 22 May

1874 to mark the anniversary of the death of the Manzoni. The orchestral

musicians are from the Orchestra Symphonica Toscanini. This was founded

in Rome in 2006 and consists of some two hundred young and highly

skilled musicians, all of whom were selected by Lorin Maazel, the

orchestra's Music Director for life. He conducted this performance.

There are times in the opening sequence where the concentration is

as much on Maazel walking through Venice as on the wonderful surrounding

city, St Mark’s Square and the Campanile and I wondered who

was being celebrated!

After the reverential and ecclesiastical style of the opening Requiem

and Kyrie (CHs. 2-3) the music varies between the beautifully

lyric and the heavily dramatic as in the Dies irae and Tuba

mirum (CHs. 4-5). At its premiere the soloists were renowned opera

singers. Ever since, as here, it is conductors and singers with that

background who seem best able to bring out its strengths, both spiritual

and vocal. The solo quartet here is well balanced vocally and includes

native Italians and Slavs for whom the Latin text holds no problems.

The two Italians, the soprano, Norma Fantini and tenor, Francesco

Meli have sung at the best operatic addresses. Both sing with good

lyric tone and enunciation of the text. Anna Smirnova, a low mezzo,

is a considerable vocal strength as is bass Rafal Siwek, who also

appears in the Florence performance conducted by Zubin Mehta (see

review).

His Mors, mors stupebit (CH. 6) is solid and tuneful. Smirnova

has the required resonance and power sufficient to make her mark throughout,

particularly in the Liber scriptus (CH.7) and - with her soprano

colleague - in the later Recordare (CH.10). It is to the soprano,

alongside the choir that the long Libera me depends with its

clear echoes of the Messe per Rossini referred to. Both are

very good with Norma Fantini’s gleaming clear tones rising and

soaring in the resonant acoustic (CHs.18-21). This resonance of the

Basilica makes the separation, in spatial terms, of the singers’

individual voices and those of the chorus and orchestra problematic.

That said, the views of the gold interior will serve as a poignant

reminder to anyone who has ever visited and been amazed at the awesome

beauty of the interior.

The chorus are vibrant and committed. On the rostrum Lorin Maazel

does little to convince me of his Verdian credentials. Conducting

without a score he fails to stir my inner spirit in the way that Karajan

and Abbado do in this most magnificent, and operatic style setting,

of the Latin Mass.

Robert J Farr

Masterwork Index: Verdi's

requiem

|

All Nimbus reviews

All Nimbus reviews