|

|

|

|

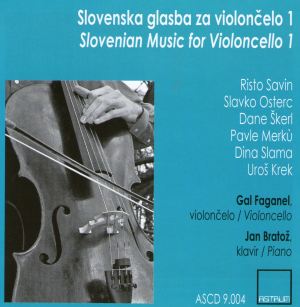

Slovenian Music for Cello and Piano - Volume

1

Risto SAVIN (Friderik

ŠIRCA) (1859-1949)

Sonata for Violoncello and Piano, op.22 (1922) [17:25]

Slavko OSTERC (1895-1941)

Partita for Violoncello and Piano (1929) [14:00]

Dane ŠKERL (1931-2002)

Two meditations for Violoncello and Piano (1989) [5:09]

Three Intermezzos for Violoncello Solo (1987) [10:06]

Pavle MERKÙ (b.1927)

Madrigal for Violoncello Solo (1985) [3:58]

Dina SLAMA (b.1941)

Song for Violoncello (1994) [3:47]

Uroš KREK (1922-2008)

Sonata for Violoncello and Piano (1984) [22:22]

Gal Faganel (cello), Jan Bratož (piano)

Gal Faganel (cello), Jan Bratož (piano)

rec. St. Anne Parish Church, Tunjce, Slovenia; Hall of St. Stanislav’s

Institution, Ljubljana, Slovenia, 1-4 July 2008.

ASTRUM ASCD 9.004 [77:13]

ASTRUM ASCD 9.004 [77:13]

|

|

|

With this disc to review I can’t help opening with British

comedy icons Monty Python’s famous phrase “and now

for something completely different”. Slovenian music for

cello and piano and solo cello and what a discovery! To say

that I know nothing about music from Slovenia is not to overstate

the case. That’s one of the many joys of reviewing: the

learning curve is never ending.

The first surprise is that the composer of the first piece on

the disc is by someone who literally led a double life. Risto

Savin, composer, was born Friderik Širca and was a General

in the army! As a composer he is credited with creating a Slovenian

national tradition of opera. In his Sonata for Violoncello

and Piano, op.22, written in 1922, each instrument is given

an equal role. I imagine it is quite tricky to play as the cello

is predominantly in the lower register whilst the piano is well

above. The opening movement’s main theme is beautifully

rich and, though the work was written in the 1920s it has much

more in keeping with one written in the late 19th

century. The first impression is that you are listening to a

piece by Brahms or Mendelssohn. In common with Brahms there

is much reference to the folk heritage of the region and it

is impossible not to know that we are in ‘central Europe’.

The second short movement has a lovely opening theme too as

does the third. The whole work brims with ideas, all of them

thoroughly explored and exploited. It is a piece that is highly

enjoyable with lush melodies and I imagine one would never tire

of hearing it.

Though written a mere seven years after Savin’s work Slavko

Osterc’s Partita for Violoncello and Piano is a

world away in style with its roots firmly in the 20th

century. Osterc’s teachers included Emerik Beran, a pupil

of Leoš Janáček as well as Vítězslav

Novák and Alois Hába. The work begins with

spiky rhythms introduced on the piano before the cello joins

in to share them. The second movement begins much more calmly

with a melancholy theme on the cello which then becomes agitated.

The piano part mirrors the mood before calm is restored. A short

Interlude comes next in which the piano has the role

to itself, the cello taking no part at all. The final Fugue

has both instruments with an equal share of the material. It

completes a work that is a perfect example of the kind of modernist

experimentation that was prevalent in the interwar years.

Two short works by Dane Škerl follow, the first, Two

meditations for Violoncello and Piano was composed in 1989.

It can be considered an example of Slovenian avant-garde and

though stark in nature it is attractively melodious. His Three

Intermezzos for Violoncello Solo which dates from 1987 is

also spare but beautiful, exploiting the full range of the cello’s

register from its very lowest voice to its topmost notes across

three short movements. Pavle Merkù’s short Madrigal

for Violoncello Solo from 1985 is again avant-garde but

as he himself put it so eloquently “In contemporary music

I search - just like my predecessors did in the past - for directness,

experience and originality. What we termed ‘contemporary

music’ or ‘avant-garde’ (or call it by any

other name you like!) is in actual fact the expression of our

times. Just like all past periods, the present yields weeds,

degenerated crops and all kinds of speculation. However, it

also produces many great and true works of art. The development

of contemporary music can bestow on us absolutely nothing new

under the Sun”. Indeed, and I thought of that especially

when 2½ minutes in comes a little tune that reminded

me immediately of “Cherry Ripe”.

Dina Slama is the only Slovene woman composer represented here.

Her Song for Violoncello written in 1994 is another beautifully

simple piece that fully exploits the cello’s wonderfully

expressive eloquence. The final work on this fascinating disc

brings the piano back for Uroš Krek’s Sonata for

Violoncello and Piano, a substantial three movement work dating

from 1984. This is full of long flowing lines and a particularly

attractive tune in the second movement.

This disc is entitled Slovenian Music for Violoncello 1,

implying that there will be further releases of this repertoire

which will be worth hearing if this one is anything to go by.

It is a credit to a small country like Slovenia with a population

of little over two million that it has produced as many composers

as it has. The music is really interesting and memorable. There

are so many works as yet undiscovered and it is wonderful to

have the opportunity to hear them. This disc was a revelation

to me and will be to any music-lover. The two soloists play

the works with passion, commitment and skill and they have been

well recorded.

Steve Arloff

|

|