|

|

Jean FRANÇAIX (1912-1997)

Musique de chambre

CD 1

String Quartet (1937) [13:00]

Sonatina for violin and piano (1934) [11:44]

Theme and variations for clarinet and piano [8:58]

Divertissement for piano and string trio (1933) [21:32]

CD 2

Decet for string quintet and woodwind quintet (1987) [18:32]

Eight bagatelles for piano and string quartet (1980) [9:23]

Nonet after the Quintet K452 by Mozart (1995) [24:51]

CD 3

Octet for clarinet, French horn, bassoon, and string quintet (1972) [22:23]

Divertissement for bassoon and string quintet (1942) [9:16]

Quintet for clarinet and strings (1977) [26:39]

L’heure du Berger for piano and string quintet (1947) [9:34]

Octuor de France; Jean Françaix (piano and direction); David Braslawsky (piano) (CD3)

rec. 1996, College Sainte Marie a Antony (CDs 1-2); February 2012, Studio Sequenza, Montreuil sous Bois, France (CD3)

INDÉSENS INDE043 [3 CDs: 55:13 + 52:46 + 67:52]

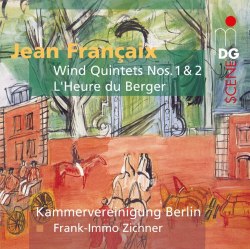

Musique pour cinq vents

Woodwind Quintet No 1 (1948) [20:03]

L’heure du Berger for piano and wind quintet (1947) [7:32]

Woodwind Quintet No 2 (1987) [20:11]

Frank-Immo Zichner (piano) (L’heure)

Kammervereinigung Berlin

rec. September 1993, Fürstliche Reitbahn Arolsen, Germany

MUSIKPRODUKTION DABRINGHAUS UND GRIMM MDG 603 0557-2 [47:46]

Jean Françaix is the pumpkin spice latte of 20th century composers. I don’t know if that will make any sense to people who don’t frequent Starbucks, but hear me out: his music is sweet, satisfying, and pleasantly warm; it’s spicy without being bitter, and it’s flavourful without being overpowering. The serious coffee-hounds will order something more forbidding like an acidy double espresso, but if you’re like me and only want to keep your taste buds happy, you’ll be after the pumpkin spice latte … and that’s Jean Françaix.

On he ploughed from the 1920s to the 1990s, unperturbed by the waves of serialism, Boulez-ism, avant-garde-ism, and every other -ism, writing gently witty music which seems to reside permanently in the cafés of 1920s Paris. Here we have two complementary reissues which, together, give you a delicious tasting menu of his chamber music.

Up first is a single CD featuring the woodwind quintets, recorded by MDG in 1993. The first woodwind quintet sets the tone immediately: warm, mellifluous music with good tunes and cheeky twists. The scherzo skitters about like chattering squirrels. The whole quintet is suffused with such energy that even the purported slow movement can barely get its theme out before sashaying into jazzy variations. L’Heure du Berger is even more forthright about its funniness: a trio of satirical portraits, it depicts things like old dandies in bow-ties and “Pin-up Girls”. The second quintet features a scurrying toccata and a slow movement which has the oboist switch to English horn for a long solo. The CD’s playing time is just 47 minutes, but they’re relaxing fun.

More substantial is the box set from Indésens, which doesn’t duplicate a single work. Actually, L’Heure du Berger appears again, but in an arrangement for piano and strings rather than winds.

The first disc contains the sprightly - and short - string quartet, which would make a terrific filler for a Debussy and Ravel quartet album. There’s also a sassy violin sonatina with hints of sarcasm and melancholy; notice the nocturnal andante and a sombre interlude in the finale. Add to this a delightful set of variations for clarinet and piano; and a piano quartet which to some extent assigns the piano and the strings separate personalities. They tend to balance each other, with, at any given time, one performer more playful and the others urging a bit of relaxation. Notice the long dream-like interlude in the finale where the piano falls silent.

The second disc of this box starts with the Dixtuor (1987), for string quintet and wind quintet combined. A brief woodwind-only introduction leads to a main theme of laid-back tranquillity, like a pastoral scene. Notice that the first movement has a slow outro, too, which explains the lack of an independent slow section. The second half of the piece is a delightful scherzo and a finale with solo licks for the first violin and the flautist switching over to piccolo.

Then we have a set of bagatelles for string quartet and piano (1980), which begin in a rather abrupt, astringent style: not typical of Françaix. Slowly the ensemble begins to push itself forward from fragmentary ideas - presented in solo and duet - into cohesive musical lines. This is highlighted by a lonely cello solo and the dramatic build-up to the finale, in which our composer finally reveals his true voice. CD 2 concludes with, of all things, Mozart’s Quintet K452, re-written by Françaix for winds and strings. The interplay definitely does not feel fully formed - the two instrument groups mostly stick together, rather than mingling - but I listened with pleasure. I was gratified by some of the ways Françaix found to compensate for the absence of piano with lyricism and grace.

The third disc begins with my favourite work in the set, if it’s possible to single one delight out of the assortment. The octet for clarinet, horn, bassoon, string quartet and double bass starts with a rather breathtaking stab at serious mood-setting. The clarinet and bassoon alternate autumnal solos, wistful and nostalgic, in a way which suggests the composer is letting his guard down. After a few minutes, though, the customary party is underway. This is both the joy and the frustration of Françaix: he never seems to grow or change or evolve. On the other hand at least the unwavering authorial voice is always fun to hear. Even in his world, the old-fashioned waltz which concludes the Octet, with sliding violins and agile dancing feet, is a moment of sheer inspiration.

The Divertissement for bassoon and strings, modestly-sized at nine minutes, gives that instrument a flashy moment in the spotlight. You can also hear some challenging, entertaining solo writing for the double bass. Clarinet quintets, on the other hand, have a bit of a pedigree as a Serious Thing (consider Brahms), and there is definitely some of that here. Françaix makes it three entire minutes, including a brief and strikingly modern clarinet cadenza, before - wouldn’t you know it - his sombre adagio moves into a perkier gear. The real standout is the grave slow movement, which really does sound like somebody else: think the adagio of Ravel’s piano concerto.

Having four CDs of chamber music like this might well be too much of a good thing. If all you hear is the Octet and L’Heure du Berger, you will only be missing more of the same. If you want serious music with formal rigour and emotional import, the bagatelles are pretty much it. On the other hand, this is all really quite a frothy delight, like that tasty drink at the coffee shop. I keep buying more and more of those.

Sound quality is consistently very good despite a variety of venues and dates. In both cases, though, the woodwind players can get breathy in their solos. Jean Françaix himself plays piano on the first two discs of the Indésens box.

Brian Reinhart

|

|

|