|

|

|

Buy

through MusicWeb

for £12 postage paid World-wide.

Musicweb

Purchase button |

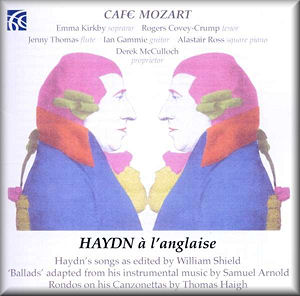

Haydn à la anglaise

Franz Joseph HAYDN (1732-1809)

The fleeting hours, ballad (duet) (after H I,74/4) [1:14]

Morning, ballad (after H I,53/2) [2:05]

Love in Return, song (after H XXVIa,16) [3:20]

Sailor's Song, canzonetta (H XXVIa,31) [2:32]

Thomas HAIGH (1769-1850)

Rondo No. 1 (after H XXVIa,31) [4:20]

Franz Joseph HAYDN

Too late, Mother, song (after H XXVIa,12) [2:38]

An old story, song (after H XXVIa,4) [2:39]

Contentment, song (after H XXVIa,20) [2:12]

The manley Heart, song (after H XXVIa,6) [4:03]

Youth and Beauty, ballad (after H I,77/4) [2:57]

The Comforts of Inconstancy, song (after H XXVIa,16) [2:43]

Thomas HAIGH

Sonata No. 1: Aria con Variazione [3:33]

Franz Joseph HAYDN

Werter's Sonnet, ballad (after H III,23/1) [2:25]

The Knotting Song, song (after H XXVIa,1) [5:11]

Peace and Content, ballad (after H III,41/4) [1:49]

My Mother bids me bind my Hair (A Pastoral Song),

canzonetta (H XXVIa,27)

Thomas HAIGH

Rondo No. 3 (after H XXVIa,27) [5:22]

Franz Joseph HAYDN

Molly Carr, song (after H XXVIa,10) [3:55]

Evening, ballad (after H I,73/2) [2:57]

Life is a Dream, song (after H XXVIa,21) [3:29]

Café Mozart (Emma Kirkby (soprano), Rogers Covey-Crump (tenor),

Jenny Thomas (transverse flute), Ian Gammie (guitar), Alastair Ross

(square piano))/Derek McCulloch

Café Mozart (Emma Kirkby (soprano), Rogers Covey-Crump (tenor),

Jenny Thomas (transverse flute), Ian Gammie (guitar), Alastair Ross

(square piano))/Derek McCulloch

rec. 7 - 9 June 2011, Rycote Chapel near Thame, Oxfordshire, UK.

DDD

NIMBUS ALLIANCE NI6174 [62:31]

NIMBUS ALLIANCE NI6174 [62:31]

|

|

|

One of the features of the last decades of the 18th century

was the flowering of the music printing business. It took profit

from the increasing popularity of music-making among the affluent

parts of the middle class. As a result there was a huge demand

for music to be sung and played in the intimacy of the private

home or in social gatherings. Obviously music-loving citizens

would like to have access to the music by the most famous masters

of their time. Earlier in the 18th century it was Handel who

was the hottest composer in Britain. By the end of the century

he had been supplanted by Haydn – the dominant force in European

music. When he was invited to visit England his friend Mozart

advised against it, saying that he didn't speak the language.

Haydn replied, “My language is understood everywhere”. He was

referring to his music, and he was right.

The title of this disc suggests that we get here some of the

music which Haydn composed during his stays in England. That

is not the case. What is offered is some of the music which

was printed in London, in particular by Longman & Broderip,

well before Haydn's first visit to London in 1791. Two

collections of German songs which Haydn had published in 1781

and 1784 were printed with either English translations of the

original German text or with new texts which had little or nothing

to do with the original. In addition two collections with ballads

were printed which were based on melodies from Haydn's

music which seemed suitable to be turned into songs. Among them

are movements from symphonies and string quartets. The third

category tackled by this disc involves three keyboard pieces

by Thomas Haigh. His two rondos are from a much later date as

they are based on two of the Canzonettas which Haydn composed

in England. Thjey were printed in 1794 and 1795. The two rondos

are preceded by the canzonettas on which they are based. These

are the only original Haydn pieces included in the programme.

One may conclude that this is a highly original disc with repertoire

probably never recorded before. From the liner-notes by Derek

McCulloch one can gather that a lot of effort has been invested

in this project. The connections between the arrangements and

the originals are given in the booklet. There is much background

information about the new texts with which Haydn's music

was underlaid. This way an interesting picture is given about

domestic music life in the last decades of the 18th century

in London. A couple of comments need to be made.

The material isn't always performed as it was printed.

The fact that some liberties have been taken in adding instrumental

introductions to the songs - in particular by the flute - is

fair enough. It will certainly reflect the way the material

was treated at the time. The flute was a very popular instrument

among amateurs. But McCulloch also decided to change the texts,

for various reasons. In some cases Haydn set words which were

German translations of original English poems. The English arrangers

were not aware of that, and translated them back, as it were.

In some cases McCulloch decided to use the original, although

these had to be adapted in several cases to fit the music. In

some songs he thought the adaptation of the German original

wasn't good enough and made his own. In his comment on

Too late, Mother (an adaptation of Die zu späte

Ankunft der Mutter) he writes that "[the] original

text was too risqué for William Shield [the arranger], who substituted

it with a blander text An invocation to Venus".

McCulloch, who apparently missed the original content, provided

his own translation. In another work, Peace and Content,

he decided to combine the text of one adaptation with the musical

material of another.

This may make sense from a strictly musical point of view, but

as those who have read previous reviews from my pen know I tend

to assess recordings from a predominantly historical angle.

From that perspective I am not that happy with these decisions.

It may be true that - as McCulloch writes - several English

texts are 'distortions' of the originals, but

they give a true picture of performance practice of the late

18th century, and the way the growing market of amateur musicians

was served. Why should this picture be adapted to modern taste?

Nobody would ever think to do so with a picture in the National

Gallery. I strongly believe that it is always better to stick

to what has come down to us from history. If we don't

like it, we can always decide not to perform it.

That said, I have greatly enjoyed what is offered here. The

performances are stylish and creative, and the singing and playing

is mostly very good. Emma Kirkby has lost nothing of her interpretational

skills; nor has Rogers Covey-Crump. During his career the latter

has sung many parts for a high tenor. It is notable that in

particular in his high register a nervous wobble creeps in.

When he has to sing forte his voice becomes a little unstable.

The use of a square piano underlines the character of the repertoire

as being intended for domestic use. The involvement of a guitar

reflects more the practice in Germany than in Britain, as McCulloch

admits. "If that brings an à l'allemande

element into proceedings, then this is not totally inappropriate,

given the significant number of first and second generation

Germans in the musical and cultural life of England at the end

of the 18th century". That is one way to put it. The argument

that the harp - which was an alternative to the keyboard among

English middle class families - is absent from Café Mozart is

less convincing. As far as I know there are various fine specialists

of the historical harp in Britain. I can hardly believe that

none of them would have liked to participate in this project.

One last item: in the canzonetta My mother bids me bind

my hair, also known as A Pastoral Song, Ms Kirkby

sings "'Tis sad to think the days are past"

instead of "the days are gone". This way the line

"I sit upon this mossy stone" fails to rhyme. What

is the reasoning behind this change? In Emma Kirkby's

recent recording of Haydn songs (Brilliant Classics) she sings

the text as it is written and printed in the booklet.

Johan van Veen

http://www.musica-dei-donum.org

https://twitter.com/johanvanveen

John Sheppard also listened

to this disc

Although Haydn first visited England in

1791 he was well known there long before that. Publishers were

understandably eager to take advantage of this, and the two sets

of songs that Haydn published in Vienna in 1781 and 1784 provided

a suitable opportunity. The composer William Shield (1748-1829)

adapted the first set in 1786 as “Twelve Ballads” and the second

was adapted by an anonymous editor in 1789. Extracts from both

sets are included here, with verses whose relationship with the

original verse is at times remote. Samuel Arnold (1740-1802) produced

a set of “Twelve Ballads” in 1787 which differ from the others

in being vocal arrangements of instrumental movements. Again there

are examples here, including the last movements of Symphonies

Nos. 74 and 77, the second movement of Symphony No. 53, and two

movements from string quartets. These alone would probably make

the disc an irresistible curiosity to any Haydn enthusiast but

that is guaranteed by the inclusion of three piano pieces by Thomas

Haigh, a student of Haydn in 1791-2. These comprise two Rondos

based on two of Haydn’s English Canzonettas, also included

here, and a set of variations based loosely on the second movement

of Symphony No. 53 which is also the basis for one of the Ballads.

Admittedly Haigh’s pieces serve more to show by comparison just

how good a composer Haydn was, but they are interesting as further

proof of the latter’s impact on the English musical scene.

All of this music was essentially intended for the well-to-do

domestic market and very properly it is sung and played accordingly,

albeit with a technical security and panache that you would probably

have been very lucky to encounter in their intended settings.

The two singers make the most of the words, and whilst they are

printed in the booklet their admirable diction makes this unnecessary

for most of the time. Three accompanying instruments – square

piano (from c1798), guitar and flute – are used, thus ensuring

ample variety of tone. Admirable booklet notes by Derek McCulloch

from which I have drawn much of the above information set the

scene clearly for the listener.

It would be idle to regard the contents of this disc as much more

than a very entertaining curiosity; something is lost in almost

every case from Haydn’s originals. Nonetheless it becomes immediately

clear just why the English took so enthusiastically to his music.

It simply “works” so well in its new context. This is one of those

discs that fills admirably a gap you probably never knew was there,

and which, for me at least, is likely to be one I will return

to often for sheer pleasure in its innocent music-making.

John Sheppard

|

|

All Nimbus reviews

All Nimbus reviews