|

|

|

Buy

through MusicWeb

for £16 postage paid World-wide.

Musicweb

Purchase button |

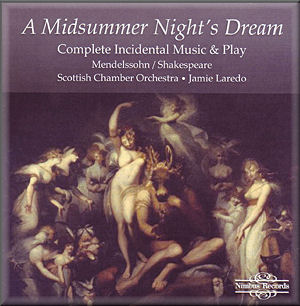

Felix MENDELSSOHN

(1809-1847)

A Midsummer Night’s Dream (William Shakespeare

(1564-1616))

Overture, Op.21 [11.44]; Incidental music, Op.61 [100.08]

(with play adapted by Adrian Farmer)

Eirian James and Judith Howarth (sopranos): Scottish Philharmonic

Singers; Scottish Chamber Orchestra/Jaime Laredo

Eirian James and Judith Howarth (sopranos): Scottish Philharmonic

Singers; Scottish Chamber Orchestra/Jaime Laredo

with John Holbeck (Theseus, Snout); Susan Oliver (Hippolyta,

Helena); Ian Sexon (Egeus, Philostrate, Bottom); Helen McGregor

(Hermia, Fairy); William Elliott (Demetrius, Flute); Ray Dunsire

(Lysander, Quince, Snug); William Blair (Puck, Starveling); Richard

Greenwood (Oberon, Snout, Cobweb); Elizabeth Phillips-Scott (Titania)

rec. 1985 using Ambisonic microphones; Venue and date otherwise

unstated

NIMBUS NI 5041/2 [54.42 + 57.10]

NIMBUS NI 5041/2 [54.42 + 57.10]

|

|

|

Mendelssohn’s incidental music to A Midsummer Night’s Dream

is one of those theatrical scores, like Grieg’s Peer Gynt,

which loses immeasurably by being given in the form of orchestral

suites without dialogue. Much of the music is written to be

performed as ‘melodrama’, that is, spoken over orchestral accompaniment.

Without the voices much of the dramatic impact which the composer

intended is lost. So it makes sense to perform the score, as

here, in the context of an abridged version of the Shakespeare

play for which it was originally composed.

When this is done, it is essential that the interplay between

music and dialogue is tightly maintained so that there are no

unseemly delays or mismatches between the two. This is certainly

achieved here, for the actors are in the same acoustic space

as the orchestra. The recording venue is not given, but to judge

from the booklet photographs it does not look like the reverberant

hall at Wyastone Leys where so many Nimbus recordings are made

although it sounds very similar. This means that the actors

are set slightly back in a realistic theatrical ambience and

not in the close-up focus to which listeners may be accustomed.

It works well, although the voices of the actors are sometimes

somewhat lacking in immediacy when they move away from the microphone.

The doublings of the actors are somewhat peculiar – sometimes

they are taking two distinct roles in the same scene, adopting

different accents. The mechanicals appear to be decidedly Scottish,

while the various pairs of lovers and the fairies - including

the proletarian Puck - are very English. Adrian Farmer’s abridgement

of the Shakespeare play is sensible, and no elements of the

disparate plot are lost; while there is plenty of sense of stage

movement in the placement of the actors. They are perhaps not

the most characterful of performers, but their nicely paced

delivery will perhaps better bear repetition than any barnstorming

would.

After the overture – written by the teenage Mendelssohn some

thirty years before the rest of the score – the whole of the

First Act of Shakespeare’s play is devoid of incidental music;

just over eight minutes of dialogue here. As we move into the

enchanted wood, the orchestral cues come thick and fast. After

the Scherzo, in the scene between Puck and the Fairy,

Jaime Laredo is not quite as prompt in picking up the cues as

one might wish. The final fragmentary reminiscence of the scherzo

- which should perhaps underpin dialogue – although the cues

in my score only give the German translation which Mendelssohn

originally used - is played between spoken phrases.

The brief snippets of music make much better logic here than

in the context which we sometimes hear them, where they are

played one after the other without any sense of the dialogue

which they are intended to illustrate. The underpinnings of

the scenes where Oberon and Puck enchant the lovers and Bottom,

for example, positively require the dialogue in order to make

any sense at all of the music. It is perhaps odd that Mendelssohn

composes no music for the song which Bottom sings and which

awakes Titania. The tune employed here fits well with the quotations

from the overture which are sprinkled throughout the scene.

The extensive melodrama passages which in the score constitute

No.6 (practically all of Act Three of the play – including the

dialogue this is by a considerable margin the longest movement

in the score) are split between the two CDs, but the break makes

dramatic sense.

Jaime Laredo uses a smallish orchestra, matching the size which

Mendelssohn might have expected. The balance is excellent with

the strings well defined and the woodwind – not too predominant

– nice and characterful. There are innumerable recordings of

this music, and listeners may well prefer a larger and more

upholstered sound, but there is nevertheless plenty of body

here. The romantic Nocturne is beautifully played with

the right sort of impassioned dreaminess, and the famous Wedding

March has all the panache that one would wish at a proper

Allegro vivace speed. The delightful reprise of a passage

from the Nocturne (with a new string counterpoint)

that underlines Oberon’s words “Come, my queen, takes hands

with me” is a real emotional highlight. Incidentally the (in)famous

passage for ophicleide in the Bergomask Dance sounds

as though a real ophicleide was used, or maybe it is just a

deliciously vulgar tuba. It is much less noticeable in the similar

passage in the Overture, and the clearly deliberate

distinction shows how carefully the dramatic side of the music

has been considered.

The play-within-a-play Pyramus and Thisbe has almost

no incidental music until the little funeral march - often played

as a purely instrumental number without the dialogue intended

to be spoken over it - at the end, and constitutes the second

longest passage of spoken dialogue (about seven minutes) in

this recording. The actors here don’t make as much of the humour

as they might. The result is the one point in this recording

which drags a little; Ian Sexon as Bottom sounds more than a

little like Billy Connolly here. The final scene, from the Bergomask

Dance onward, is a real delight. First we have the diminuendo

reprise of the Wedding March which leads into the opening

chords of the overture, sustained under Oberon’s words “Through

the house give glimmering light”. This music really only makes

sense with the dialogue. Recording both simultaneously means

that the correlation between the two can be precisely judged.

There are several other recordings of the Mendelssohn score

which make use of actors (many very distinguished) to speak

the dialogue in the appropriate places. All those I have heard

have clearly been post-dubbed, with the speaking voices set

down over previously recorded orchestral tracks. This may be

inevitable where CDs are destined for the international market,

but it seems to me that Shakespeare’s text deserves to be heard

in the original language, just as we accept much inferior spoken

dialogue when we listen to recordings of German and French operettas

by Strauss and Offenbach. The give-and-take of recording speakers

and orchestra at the same time - even if sometimes the interchange

could be crisper here - pays considerable dividends. Those who

are allergic to the speeches may be disappointed to find that

the tracking on these CDs does not allow the dialogue to be

skipped, but they will miss the essential element of drama which

is implicit in Mendelssohn’s score. Non-English speaking listeners

should however note that no texts or translations of the play

are given in the booklet.

As a recording of the Shakespeare play and Mendelssohn’s incidental

music treated as an integral unit, then, this is very much a

set which stands unchallenged in the catalogue. Its only rival

for completeness - and the text is much more heavily cut - comes

from mainly Parisian forces conducted by John Nelsons, with

a cast of genteel and anonymous actors from the “Oxford and

Cambridge Shakespeare Society” who are located in a clearly

different acoustic from the singers and orchestra. Listeners

who love this music, one of the greatest works ever written

for the spoken theatre, should experience it in its dramatic

context; afterwards hearing the music shorn of the dialogue

will be discovered to be forever unsatisfactory.

Paul Corfield Godfrey

|

|

All Nimbus reviews

All Nimbus reviews