|

|

|

alternatively

MDT

AmazonUK

AmazonUS |

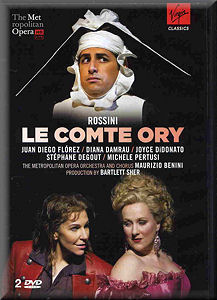

Gioachino ROSSINI

(1792-1868)

Le Comte Ory - an opera in two acts (1828)

Count Ory, a young and licentious nobleman - Juan Diego Florez

(tenor); Countess Adele - Diana Damrau (soprano); Isolier, page

to Count Ory and in love with the Countess Adele - Joyce DiDonato

(mezzo); Raimbaud, friend to Count Ory - Stéphane Degout

(baritone); Governor, tutor to Count Ory - Michele Pertussi (bass);

Ragonde, companion to Countess Adele - Susanne Resmark (alto)

Count Ory, a young and licentious nobleman - Juan Diego Florez

(tenor); Countess Adele - Diana Damrau (soprano); Isolier, page

to Count Ory and in love with the Countess Adele - Joyce DiDonato

(mezzo); Raimbaud, friend to Count Ory - Stéphane Degout

(baritone); Governor, tutor to Count Ory - Michele Pertussi (bass);

Ragonde, companion to Countess Adele - Susanne Resmark (alto)

Chorus and Orchestra of the Metropolitan Opera, New York/Maurizio

Benini

Producer: Bartlet Sheer

Set Designer: Michael Yeargen Costume Designer: Catherine Zuber

rec. 9 April 2011

Picture format: NTSC 16.9; Region free. Colour HD. Sound: LPCM stereo.

Subtitles: English, French, German, Spanish, Italian

VIRGIN CLASSICS 0709599

VIRGIN CLASSICS 0709599  [2 DVDs: 153:00 plus bonus]

[2 DVDs: 153:00 plus bonus]

|

|

|

Afterthe premiere of Semiramide in Venice on 3

February 1823 Rossini and his wife travelled to London via Paris.

There the composer presented eight of his operas at the King’s

Theatre, Haymarket, and also met and sang duets with the then

King. The stay was reputed to have brought Rossini many tens

of thousand pounds. On his return to Paris, Rossini was offered

the post of Musical Director of the Théâtre Italien.

His contract provided an excellent income and a guaranteed pension.

It also demanded new operas from him in French, a command of

which linguistic prosody he needed to learn. Before any such

tasks however, came the unavoidable duty of a work to celebrate

the coronation of Charles X in Reims Cathedral in June 1825.

Called Il viaggio a Reims (A Journey to Reims) it was

composed to an Italian libretto and presented at the Théâtre

Italien on 19 June. It was hugely successful in a handful of

sold-out performances after which Rossini withdrew it, considering

it purely a pièce d’occasion.

Rossini’s first compositions to French texts for The Opéra

were revisions of earlier works with new libretti, settings

and additional music. Le Siège de Corinthe, the

first, was premiered in October 1826 and was a resounding success

with Moïse et Pharon, a revision of the Italian

Mosè in Egitto, following in March 1827 to even

greater acclaim. During the composition of Moïse et

Pharon, Rossini agreed to write Guillaume Tell. Before

doing so he wrote Le Comte Ory, to a wholly new French

libretto. In doing so he made use of no fewer than five of the

nine numbers from Il viaggio a Reims.

The use of the five numbers from Il viaggio, mainly in

the first act, gives a distinctly different tinta to

the music between the two acts of Le Comte Ory. Itis

not a comic opera in the Italian tradition, where secco

recitative was to last another decade or so, but more in the

French manner of opéra-comique. There are no buffoon

characters and no buffa type patter arias. The work is one of

charm and wit in the best Gallic tradition and with, perhaps,

a look towards Offenbach. The plot concerns the Countess Adele

and her ladies who swear chastity and retreat to the Countess’s

castle when their men go off to the crusades. Comte Ory, a young,

licentious and libidinous aristocrat is determined to gain entrance

to the castle in pursuit of carnal activity. He first does so

as a travelling hermit seeking shelter and charity. When this

fails he returns disguised as the Mother Superior of a group

of nuns, really his own men in disguise and who also fancy their

chances with the pent up ladies. His young page, Isolier, a

trousers role, himself in love with the countess thwarts Ory’s

plans. The timely return of the crusaders does likewise for

the intentions of Ory’s fellow ‘nuns’. Love

remains ever pure and chastity unsullied!

This recorded performance is the same as was transmitted to

cinemas worldwide on the Saturday evening shown. At a cinema,

I waited with worried anticipation for a front of stage announcement,

as the performance was a little later than usual in starting.

None was forthcoming, but in the interval talk, repeated here

as part of the bonus of interviews conducted by soprano diva

Renée Fleming, it emerged that tenor Juan Diego Florez

had been in the birthing pool with his wife shortly before hurrying

to the theatre for the performance after the arrival of a son!

He was on a high and by the end of the performance so were we,

at least in respect of the singing.

Bel canto and the Metropolitan Opera have not always

been easy bedfellows. In the 1950s general manager Bing fell

out with Maria Callas, reigning queen of the genre. With that

separation the house ceded the genre to Allen Sven Oxenberg’s

American Opera Society. Oxenberg presented Callas as

Imogene in Bellini’s Il Pirata for its American

debut. Overnight the AOS became New York’s principal purveyor

of star operatic attractions. In February 1962 it even upstaged

the Met with Sutherland’s debut in the city singing the

eponymous role in Bellini’s long forgotten Beatrice

di Tenda. The arrival of Joan Sutherland on the scene changed

the Met’s attitude to the bel canto repertoire.

It is perhaps significant that shortly after Peter Gelb took

over as General Manager in 2006, and set about revitalising

productions, one of the earliest productions of his first season

was a revival of Bellini’s I Puritani, originally

mounted in 1976 for the great Australian diva. The revival featured

Anna Netrebko as Elvira giving a sensational rendering of the

act two mad scene (see review).

In retrospect this seemed to kick-start a significant return

to the bel canto under Gelb with a series of new productions

that were also premieres at the theatre, and even in America,

of neglected operas of that period. The sequence has included

Rossini’s Armida in 2010, this performance of Le

Comte Ory in the spring of 2011 and Donizetti’s Anna

Bolena later the same year. The composer’s Maria

Stuarda is scheduled for the 2012-2013 season. All these

productions are included in the Met’s programme of transmissions

to cinema’s worldwide. My reviews of the first and third

of those operas will appear shortly on this site.

The only downside of Peter Gelb’s policy has been in his

choice of directors and set designers. The choice often falls

to those with rather off-beat ideas and little experience of

opera. In the case of this Le Comte Ory, director Bartlet

Sheer and set designer Michael Yeargen choose the “theatre

within a theatre” concept of a presentation in the late

eighteenth century. Not a failing in itself, but do the audience

really want to see the wind-machine and thunder-sheet, let alone

the constant fussing of a period costumed and seemingly senile

stage manager roaming the set? I doubt it, and it does distract

from an excellent cast of principals and the superb and opulent

gowns for the ladies of the castle. Add a lack of cohesion,

even unintended confusion, in the three-in-a-bed pranks of the

last scene, much better handled in the 1997 Glyndebourne production

(see review),

and I dearly wished that Gelb had appointed a team with more

experience of opera and this genre in particular.

The three principal singers, Juan Diego Florez as Ory, Diana

Damrau as the Countess pursued by him and Joyce DiDonato as

Isolier, his page and rival for the countess’s affections,

could hardly be bettered. Their singing is outstanding in all

respects, all of them making the best they can of the producer’s

clichés. All three are consummate actors able to create

a character as well as being coloratura specialists. Despite

the many vocal challenges thrown at them by Rossini I hardly

heard a fluffed line or smudged or aspirated vocal division.

Spectacular high notes are hit with a purity and élan

that takes the breath away. The supporting cast includes a very

good Raimbaud, Ory’s friend in the seduction plans, in

the person and firm tones of the baritone Stéphane Degout.

There’s also a sometimes dry-toned Michele Pertussi as

Ory’s tutor. Susanne Resmark is a well-acted Ragonde with

many facial expressions that partially distract from her capacious

bosoms that look as if they are going to wobble out of her bustier

any minute. Maurizio Benini conducts with a pleasing combination

of wit and élan that allows Rossini’s creation

to sparkle.

The Virgin Classics booklet gives no chapter listings, contents

or timings. The essay explaining Bartlet Sheer’s ideas,

in English and French is no compensation for this omission.

Robert J Farr

|

|