|

|

|

alternatively

CD: MDT

AmazonUK

AmazonUS

|

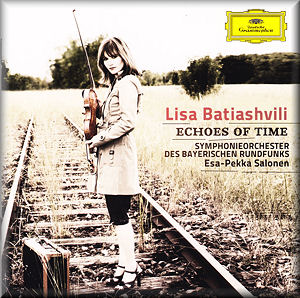

Echoes of Time

Dmitri SHOSTAKOVICH

(1906-1975)

Violin Concerto No.1 in A Minor, Op.77 (1947/48, rev. 1955) [40:07]

Giya KANCHELI (b. 1935)

V&V for violin and taped voice with string orchestra (1994)

[10:51]

Dmitri SHOSTAKOVICH (1906-1975)

Lyrical Waltz from Seven Doll's Dances for violin and orchestra

(orch. Tamas Batiashvili) (1952) [3:25]

Arvo PäRT (b. 1935)

Spiegel im Spiegel for violin and piano (1978) [10:21]

Sergei RACHMANINOV (1873-1943)

Vocalise for violin and piano, Op. 34, No. 14 (1912) [5:39]

Lisa Batiashvili (violin)

Lisa Batiashvili (violin)

Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra/Esa-Pekka Salonen (Shostakovich;

Kancheli)

Hélène Grimaud (piano) (Pärt; Rachmaninov)

rec. May 2010, Hercules Hall, Residenz, Munich, Germany (Shostakovich;

Kancheli) and November 2011, IRCAM, Espace de projection, Paris,

France (Pärt; Rachmaninov)

DEUTSCHE GRAMMOPHON 477 9299 [68:21]

DEUTSCHE GRAMMOPHON 477 9299 [68:21]

|

|

|

Titled Echoes of Time, this is a varied collection chosen by Lisa Batiashvili, “of works by composers whose artistic lives - like her own - were impacted on by Soviet life and politics.” Of the five pieces on this splendid Deutsche Grammophon release the feature work is the Shostakovich Violin Concerto No.1. Although lesser in scale the remaining four scores are still fine in their own right. I found them highly enjoyable and often fascinating.

Georgian Lisa Batiashvili is one of the most outstanding young women violinists on the international scene today. It’s a crowded place these days with most notably Hilary Hahn, Leila Josefowicz, Julia Fischer, Arabella Steinbacher and Alina Ibragimova. In May this year (2011) at the Munich Philharmonie I attended a concert with Batiashvili playing a truly beautiful account of the Sibelius Violin Concerto (a work she recorded for Sony) with a strangely lacklustre New York Philharmonic under Alan Gilbert. The present disc was also in large part recorded in Munich but a year earlier at the Hercules Hall.

I have compared Batiashvili’s recording with Steinbacher’s impressive 2006 Hercules Hall recording with the same orchestra under Andris Nelsons on Orfeo 687061A. A significant additional attraction to the Steinbacher-Nelsons disc was the inclusion of Shostakovich’s Violin Concerto No.2.

After composing his Concerto for Piano, Trumpet, and String Orchestra in 1933 it was some fifteen years before Shostakovich wrote his first string concerto the Violin Concerto No.1 completed in 1948. Owing to a climate of strict censorship in Soviet Russia in the immediate post-war years Shostakovich consigned the unpublished concerto to the drawer for a number of years. By 1955 the political climate had sufficiently mellowed to permit the score’s première by its dedicatee, the renowned soloist and David Oistrakh with the Leningrad Philharmonic under Yevgeny Mravinsky. At the publication of the full score in 1955 the opus number 77 was altered to 99. However the original opus number has now been restored. Highly praised at its première this concerto is acknowledged as one of finest of the twentieth century.

The four movement score commences with a disconcerting Nocturne (Moderato). Its desolate and bleak atmosphere develops to nerve-shattering intensity. With playing of rapt tenderness Batiashvili’s interpretation has a tearful and deep yearning quality. Steinbacher brings out more anger and distress from the writing amid episodes of intense longing. The demonical Scherzo (Allegro) has both conductors building weighty orchestral climaxes of powerful emotional impact. Batiashvili takes a brisk pace drawing out a latent tension that to threatens to explode. Her dance constantly circles round and round like a demented circus ride. The playing from the energetic Steinbacher creates a feeling of cold isolation. A sense of extreme anxiety prevails as the pace quickens. This tension-filled dance evokes an uncomfortable sense of shame and humiliation.

Probably the most celebrated movement in the concerto is the third movement Passacaglia. Developed from an ostinato figure emanating in the cellos, the music has been said to serve as a requiem for victims of the Stalinist regime. Highly assured direction from both Salonen and Nelsons conveys a rock-like power with sinister doom-laden grandeur. Both conductors manage to tighten the screw, escalating the tension and sheer declamatory power to an almost unbearable level. With Batiashvili one feels a sense of isolation with the pining violin sobbing its heart out. Similarly, as if her instrument was weeping Steinbacher plays with a marked mournful quality imparting rather more rawness. Both Batiashvili and Steinbacher are outstanding in the cadenza an unremitting rhapsodic melody of a progressively disconsolate and introverted character. The soloist’s line becomes less melodic, increasingly discontented and more frenzied.

Following straight on the Final movement marked Burlesque: Allegro con brio - Presto is a vigorous and boisterous romp. Especially noticeable, before the soloist enters Salonen’s percussion section sounds in quite remarkable form. Strongly paced Batiashvili transmits the power of a runaway stream train travelling at full pelt. The madcap approach to the conclusion is as breathtakingly thrilling as one could imagine. Exciting and strongly rhythmic Steinbacher’s account feels more spontaneous, galloping along with boundless reserves of energy. Now Steinbacher’s dancing violin takes on a gypsy-like freedom. With great brio the weight and intensity of her playing leaves a quite dramatic impression with the concerto ends with uncomfortably abruptness on a wild and breathless note. There is more than one way of playing this exceptional concerto with both soloists Batiashvili and Steinbacher playing superbly well and adopting noticeably differing approaches. On balance the expressive Batiashvili plays with more refinement and beauty in a way that feels wonderfully controlled; a more cerebral interpretation. Conversely Steinbacher’s interpretation is wilder, more spontaneous, displaying a wider extreme of emotion. Recorded four years apart Salonen and Nelsons with the same crack Bavarian orchestra obtain the finest support directing exceptionally well-sprung rhythms with plenty of dramatic bite.

I know Georgian composer Giya Kancheli mainly for his 1999 score Styx for viola, mixed chorus and orchestra. Now an Antwerp resident, Kancheli wrote his score V&V for violin and taped voice with string orchestra in 1994 having been inspired by the distinctive voice of Georgian singer Hamlet Gonashvili who suffered a fatal fall from an apple tree. The beginning and the concluding sections of V&V use a tape of Gonashvili’s voice taken from a 1973 recording of the Symphony No. 3. Predominantly in the high resisters Batiashvili’s mainly hushed violin playing against the slow ethereal sounds of the taped voice creates an enthralling and often haunting sound-world. Weightier waves of sound provide a welcome contrast. The string sound is beyond reproach.

Shostakovich’s Seven Doll's Dances is a suite of seven piano pieces originally arranged from the Ballet Suite No. 2. The Lyrical Waltz is presented here in the orchestrated version prepared by Lisa Batiashvili’s father Tamas. This short, eminently agreeable if undemanding waltz containing a highly memorable melody and is played with relish.

Arvo Pärt wrote Spiegel im Spiegel (Mirror in the Mirror) in 1978 prior to his leaving his Estonian homeland to avoid problems with the Soviet authorities. One of the most admired contemporary scores in circulation today Spiegel im Spiegel has been arranged for various instrumental combinations. Recorded at IRCAM, Paris in 2010 Batiashvili and Grimaud perform Pärt’s original conception of the score for violin and piano. The repetitive design and the languid quality of this exquisite score combined with such responsive and expressive playing makes for a near-hypnotic experience of poignant spirituality.

Continuing the theme of discontentment with the Soviet regime in their homeland, Rachmaninov was another composer who felt he could no longer live in the country of his birth. Following the Russian Revolution in October 1917 Rachmaninov left for Sweden later emigrating to America in November 1918. Originally a song published in 1912 Rachmaninov’s Vocalise with its arresting melody is one of the composer’s most played scores; especially as an encore. Owing to its extreme popularity with audiences the Vocalise has been arranged for numerous instrumental groupings from two pianos to jazz ensemble to twenty-four cellos. With the much admired version for violin and piano in the hands of Batiashvili and Grimaud the Vocalise becomes the epitome of tender romance.

This is a beautifully played and recorded disc of twentieth century music. Throughout Batiashvili displays a highly refined quality to her playing conveying most gorgeous tones from her 1727 Venus Stradivarius (in the Violin Concerto) and 1709 Engleman Stradivarius.

Michael Cookson

|

|