|

|

|

alternatively

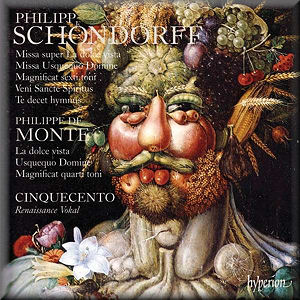

CD:

MDT

AmazonUK

AmazonUS

|

Philippe DE MONTE

(1521-1603)

Usquequo Domine oblivisceris me? a 6 [5:25]

Philipp SCHOENDORFF (1565/70-in

or after 1617)

Missa Usquequo Domine a 6 [17:19]

Magnificat 6. toni a 5 [6:32]

Te decet hymnus a 5 [2:25]

Philippe DE MONTE

Magnificat 4. toni a 4 [6:32]

Philipp SCHOENDORFF

Veni Sancte Spiritus a 5 [2:17]

Philippe DE MONTE

La dolce vista della donna mia a 6 [2:16]

Philipp SCHOENDORFF

Missa super La dolce vista a 6 [17:12]

Cinquecento - Renaissance Vokal (Terry Wey, Jakob Huppmann (alto),

Tore Tom Denys, Thomas Künne (tenor), Tim Scott Whiteley (baritone),

Ulfried Staber (bass))

Cinquecento - Renaissance Vokal (Terry Wey, Jakob Huppmann (alto),

Tore Tom Denys, Thomas Künne (tenor), Tim Scott Whiteley (baritone),

Ulfried Staber (bass))

rec. 21-23 April 2010, Kloster Pernegg, Waldviertel, Austria. DDD

Texts and translations included

HYPERION CDA67854 [60:02]

HYPERION CDA67854 [60:02]

|

|

|

Musical life in Europe in the 15th and 16th centuries was largely

dominated by the Franco-Flemish school. Everyone can name some

of the representatives of that school, like Josquin Desprez,

Nicolas Gombert or Orlandus Lassus. Those were all singers and

composers who took the most prestigious positions in cathedrals

and at royal and aristocratic courts. They are the proverbial

tip of the iceberg. Many others, who had less prominent positions

and worked as singers in chapels, have remained under the radar

of modern performers. The members of Cinquecento have a special

liking for such composers as their discography shows. They have

devoted two discs to Jacob Regnart and Jacobus Vaet. The latter

is also represented on a disc with music written for the court

of the Habsburg emperor Maximilian II. It includes again pieces

by Vaet and by another unknown master, Antonius Galli.

For the latest disc Cinquecento returns again to the Habsburg

dynasty. This time it is the court of Rudolf II which is in

the centre of attention. He was Maximilian II's son who sent

him to Spain to the court of his uncle Philip II. After his

return he was elected King of Hungary (1572) and then of Bohemia

(1575). In 1576 Maximilian suddenly died, and Rudolf succeeded

him. He moved his court to Prague, where Philippe de Monte,

one of the most distinguished Franco-Flemish masters, was his

Kapellmeister, and Philipp Schoendorff a member of the

chapel. He was not, as his name could suggest, German, but from

Liège in the southern Netherlands. Very little is known about

his origins or his formative years, except that he was educated

as a trumpeter. An important figure in his career was Jacob

Chimarrhaeus, chaplain and later almoner of the imperial court.

It is likely Chimarrhaeus introduced him to the chapel. His

career was probably helped by the fact that he dedicated his

Missa super La dolce vista to the emperor, and also paid

a tribute to Philippe de Monte, as the mass was based upon one

of his madrigals.

This work is one of the two masses which are known from Schoendorff's

pen. Both are remarkably short, in these performances less than

18 minutes each. The reason could well be that his employer,

Rudolf II, didn't like long religious services. Notable are

especially the concise settings of the Gloria which take about

three and a half minutes each. Schoendorff uses several means

to keep his masses short. There is relatively little repetition;

often the various phrases just follow each other without any

words repeated. Both masses are for 6 voices, and this also

serves the cause. By splitting the ensemble in various combinations

of voices one group can start a phrase while the other singers

are still closing the preceding phrase. This leads to a remarkable

short-windedness, without giving the impression of anything

being rushed. In the Missa super La dolce vista the syllabic

character of Schoendorff's setting also contributes to its succinctness.

Apart from the two masses only three other compositions by Schoendorff

are known: a setting of the Magnificat and the motets

Te decet hymnus and Veni Sancte Spiritus. The

Magnificat is an alternatim setting for five voices

in which the odd verses are sung in plainchant. In the polyphonic

passages we hear various specimens of ornamentation which Bénédicte

Even-Lassmann in the liner-notes explains by referring to the

composer's education as an instrumentalist. There are several

passages in which text and music are closely connected. In the

motets and the masses he also uses various musical means to

depict the text.

As Philippe de Monte was Schoendorff's superior at the court

in Prague it makes much sense to include several of his compositions

on this disc. The motet Usquequo Domine and the madrigal

La dolce vista are logical choices as they were used

by Schoendorff as starting points for his masses. The motet

is a setting of the complete Psalm 12 (13) which contains strong

contrasts between sad and joyful passages, vividly expressed

by De Monte. Bénédicte Even-Lassmann sees a connection between

this Psalm and De Monte's personal circumstances: it is considered

a work from the 1580s when De Monte was in bad health and poor

spirits. The madrigal has much of the passion and the sweetness

of many of De Monte's works. The Magnificat 4. toni is

again an alternatim setting, in which many passages are

homophonic and the tenor and bass are treated in falsobordone.

This disc presents the complete works of a hitherto largely

unknown master. He is a composer music historians like to characterise

as a 'minor master'. Considering his position and his small

output this may be justified, but it shouldn't be interpreted

in any derogatory way. There is enough that is remarkable in

his oeuvre fully to justify the attention Cinquecento is giving

him. Various reviewers on this site have sung the ensemble's

praises, and I am joining the chorus with enthusiasm. This is

singing of the highest order. All participants have very fine

voices, and the balance between them is perfect. Again I noticed

the relaxed singing of the upper voices which are without any

strain even on the highest notes. The various lines are beautifully

shaped and are easy to follow, also due to the superb recording.

The elements of text expression come off well, and the contrasts

in De Monte's motet Usquequo Domine are perfectly realised.

If there is anything to criticise it could be the habit of singing

the "Et incarnatus est" from the Credo of the masses

piano. I wonder whether there is any historical justification

for this. One could probably also question the Italian pronunciation

of Latin which may not have been practised in Prague in the

16th century.

If you are acquainted with previous releases with Cinquecento

you probably will have purchased this disc already. If you haven't

yet, don't hesitate. This is one hour of pure joy, and you can

also be sure that you hear almost only music you have never

heard before. I am already looking forward to Cinquecento's

next recording project. May their enterprising spirit never

dry out.

Johan van Veen

http://www.musica-dei-donum.org

https://twitter.com/johanvanveen

|

|