|

|

|

alternatively

CD: MDT

AmazonUK

AmazonUS

|

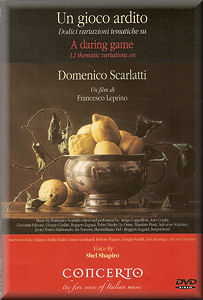

A Daring Game; 12 thematic variations on Domenico Scarlatti.

A film by Francesco Leprino

Genre, Docu-film. Code, 0. Audio and subtitles, Italian/English.

Audio Format, Dolby Digital 2.0. Video format, NTSC 16:9. Extras,

the Concerto catalogue.

CONCERTO

CONCERTO  DVD

2021 [98:00] DVD

2021 [98:00]

|

|

|

There’s an extensive apologia in the brief booklet that accompanies this DVD. It notes, with commendable honesty, that the film was shot on a very small budget on fairly basic equipment. But because of the passion enshrined for its subject, Domenico Scarlatti, the publishers hope that prospective purchasers understand and make allowances. You can’t say fairer than that – or that you haven’t been warned.

The title ‘A Daring Game. 12 Thematic Variations on Domenico Scarlatti’ might suggest the kind of thing that’s been done with Glenn Gould, but that’s not the case. This is instead a fairly basic chronology but with some bizarre features. You must accept that the English language dubbing is carried out in such a way that you can often – not always, but often – still hear the original Italian ‘underneath’. Sometimes it’s contrapuntal; sometimes it’s like a duet. But you can always hear the English; it’s just that you can also often hear the Italian too. Then there’s this business about Charles Burney. The great musical historian’s comments are mouthed via a rococo puppet, in a puppet theatre. Burney often jiggles about, his wooden mouth going at ten to the dozen, long after the English voice-over has stopped. On this subject will people of a continental disposition please note that Burney did not say that the water level in the Lisbon earthquake rose to fifteen metres? He said 50 feet or whatever. No retrospective metrication on my watch, thanks very much.

Anyway, I appreciate this is a minor aspect of the story. Burney does appear a lot though, in the form of his puppet, and it has its risible elements. The main body of the film divides into three; firstly, talking heads, academic and executant, secondly performances of Scarlatti’s music, and thirdly the puppet thing. The authorial voice-over provides an over-arching sense of continuity.

Fortunately there is a travelogue element too, so we get nice shots of Italian towns, and of Lisbon, and many of the places and buildings – royal and religious - associated with the composer. Some of the interviews are shot on rather basic equipment but the apologia covers this point and I can’t say it especially concerned me – though I did get the disc free to review and am therefore in a privileged position. You may not be quiet so forgiving. What is slightly tiresome is the occasional brusque cut-off at the end of interviews.

The musical examples used are a strange bunch. If you were expecting harpsichordists and singers recreating Scarlatti’s music you would be only partially right. Part of the programme’s brief is to propound his living importance to music; no mere statuary, this is the living breathing Scarlatti whose corpuscles now run through the avant garde. Thus we have jazz groups improvising on Scarlattian themes – Giovanni Falzone’s band for instance, whose line-up of trumpet (himself), vibes, bass and drums certainly puts a new slant on things. There’s an electronic keyboard and computer mash-up complete with kind-of feedback. And Giorgio Gaslini performs a very studied Jacques Loussier-style updating, along with his more clued-in bass player. The Lisbon segment inspires two things I did like; the (apparently) last filmed interview with José Saramago, the Nobel Prize winning Portuguese novelist and poet. We also hear the exquisite Fado singer Ana Moura, beautiful and talented, whose music I like very much: she’s up there with Misia, for me, and just as persuasive as the more fêted Mariza. Some may know that Saramago’s lyrics were sung by Fado singers over the years – a neat conjunction though, I admit, this is taking things a long way from Domenico Scarlatti. I must mention also the brief interview with the courtly and eloquent Gustav Leonhardt, who answers in English.

We watch a collage performance of Longo 380, and also a number of performers and academics chip in on the subject of L208 which many think his single most daring and spectacular proto-Romantic masterpiece. Maybe for budgetary reasons we don’t get cantata performances – though we do get a contemporary version, a rather trying one I must say. It’s especially good though to be reminded of the influence of Spanish folk music on Scarlatti, which is there for all to hear.

The speakers and musicians are captioned at the end, in the final credits, though it’s a bit difficult to work out at the time who is who and what is what.

This is certainly a strange one. It’s neither a true chronological biography, nor really a contrapuntal examination of Scarlattian themes. Yes, it’s a bit of a mess, but a warm-hearted, dedicated, polyphonic mess.

Jonathan Woolf

|

|