|

|

|

alternatively

CD: MDT

AmazonUK

AmazonUS

|

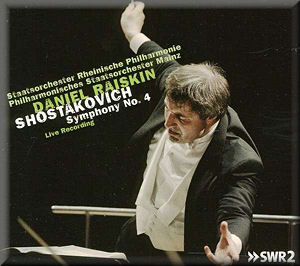

Dmitri SHOSTAKOVICH

(1906-1975)

Symphony No. 4 in C minor, Op. 43 (1936) [65:30]

Staatsorchester Rheinische Philharmonie, Philharmonisches Staatsorchester

Mainz/Daniel Raiskin

Staatsorchester Rheinische Philharmonie, Philharmonisches Staatsorchester

Mainz/Daniel Raiskin

rec. live, 19-20 March 2009, Phönix-Halle, Mainz (SWR), Rhein-Mosel-Halle,

Koblenz (Deutschlandradio Kultur)

C-AVI 8553235 [65:30]

C-AVI 8553235 [65:30]

|

|

|

An early performer likened the effect of Shostakovich’s opera

The Nose to ‘an anarchist’s grenade’, a description that

could just as easily be applied to the Fourth Symphony, written

eight years later. The latter’s a hugely talented piece and

the seedbed for much that was to take hold and germinate in

the composer’s later works. But it’s more than that; in the

right hands it’s Shostakovich’s most uncompromising and subversive

symphony. Remember, the finale of the Fourth was completed in

the immediate aftermath of Stalin’s infamous Pravda article,

with all the personal and artistic turmoil that brought with

it.

Among the most penetrating versions of this symphony on CD are

Kiril Kondrashin’s on Melodiya, Gennadi Rozhdestvensky’s Czech

radio broadcast from 1985, Neeme Järvi’s for Chandos and,

most recently, Mark Wigglesworth’s for BIS. There’s some dispute

about the exact provenance of the Rozhdestvensky, but absolutely

no doubt about his excoriating performance. Hard to beat, I

thought, until Wigglesworth burst on the scene. In many ways

this was the Fourth I’d been waiting for, combining as it does

the visceral elements of Rozhdestvensky and Kondrashin with

an implacable strength and clarity of vision that’s just astounding

(review).

Indeed, it was one of my picks for 2010, and a reading I was

sure could not be improved upon.

Enter Daniel Raiskin, the up-and-coming maestro from St. Petersburg

and, since 2005, the chief conductor of the Staatsorchester

Rheinische Philharmonie. Lest one is tempted to write off these

provincial bands, remember Wigglesworth’s Dutch radio orchestra

play Shostakovich as if to the manner born. Factor in a top-notch

hybrid recording from BIS and you’ll understand why these newcomers

elicited polite interest rather than outright enthusiasm when

the disc was offered for review.

Well, seconds into the Allegretto and any such doubts are thrust

aside by the most lacerating introduction to this symphony I’ve

ever encountered. The shrieking strings, chatter of woodwinds

and bone-crushing contributions from the percussionists simply

beggars belief. It’s not just about heft, for the alarums and

excursions that ensue are every bit as gripping, Raiskin extorting

exceptional, razor-sharp attack from his players. Wigglesworth

is broader and there’s much more air around the notes, but the

Russian’s reading – and Avi’s close recording – are alive with

detail and arcing with unrelieved electricity.

Shostakovich’s strange ditties and diversions are all uncovered

with forensic skill, the orchestra responding to this wild music

with remarkable assurance. Raiskin never allows the pace to

flag and the climaxes – judiciously scaled – are staggering

in both breadth and intensity. As for those Mahlerian crescendi,

they’ve seldom sounded so menacing, the timps so brutal. One

really is in the front row of the stalls here, and there’s no

escape from the withering fire. Even Shostakovich’s more spectral

writing is as revealing as an x-ray image, the yearning strings

most beautifully caught. But it’s Raiskin’s strong, steady pulse

that holds all these disparate elements together, the music

utterly compelling throughout.

And how winningly he phrases the opening of the Moderato. That

said, Raiskin brings something of Bartók’s nervous energy –

and colour - to the score. There’s a pleasing sense of proportion

as well, all those sardonic asides voiced with as much care

and attention as the symphony’s more spectacular outbursts.

No apologies need be made for the fact that this is a live recording,

made over two nights and in different venues; detail is abundant,

perspectives are consistent, and the audiences are very quiet

indeed.

The Largo – Allegro has a pronounced Mahlerian cast, the opening

cortege played with splendid character and weight. It’s those

gaunt little tunes that bubble up and then subside that give

this movement its abiding strangeness, that first peroration

as anguished as I’ve ever heard it. This really is a Lubyanka-like

edifice of dread and despair, as dark as anything Shostakovich

ever wrote, and Raiskin wrings the most individual sonorities

from his players. Not only that, he builds tension like few

others, that crazed march underpinned by the truly explosive

thud of timps and crowned with fevered brass.

In a work littered with frigid interludes this movement has

more than its fair share of chill-inducing moments, with Shostakovich

passing uneasily between cold terror and grim comedy. As for

that lampooning brass, it’s superbly managed, the Mahlerian

scurry beneath it deftly done. And all the while Raiskin maintains

a mesmeric tension, so that when that cataclysm finally arrives

it’s been well prepared. Goodness, this is a scream like no

other in the symphonic repertoire, the Avi engineers drawing

out every last, incandescent detail and decibel. But it’s the

haunted postlude that’s really terrifying; this is truly a blasted

heath, a no-man’s land of unimaginable bleakness. As compelling

as Wigglesworth is at this point, Raiskin distils something

quite extraordinary from the notes. The ghostly shimmer of the

celesta is indescribably moving.

Having emptied the cupboard of superlatives, all I can say is

that Daniel Raiskin is a man to watch. Like that anarchist’s

ordnance, he’s blown away every shred of smugness and complacency

I felt before hearing this phenomenal performance.

Shattering, unforgettable Shostakovich.

Dan Morgan

|

|