|

|

|

alternatively

CD: MDT

AmazonUK

AmazonUS

|

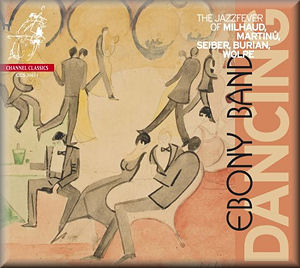

Dancing

Stefan WOLPE (1902-1972)

Suite from the Twenties [14:23]

Emil František BURIAN (1904-1959)

Suite Americaine, Op.15 (1926) [11:21]

Bohuslav MARTINŮ

(1890-1959)

Jazz Suite (1928) [11:25]

Mátyás SEIBER (1905-1960)

Jazzolette No.1 (1929) [3:15]

Jazzolette No.2 (1932) [4:01]

Darius MILHAUD (1892-1974)

La création du monde, Op.81 (1923) [16:47]

Ebony Band/Werner Herbers

Ebony Band/Werner Herbers

rec. 14 April 2007, Toonzaal, Den Bosch (Wolpe); 21 May 2007, De

Vereeniging, Nijmegen (Milhaud); 27 April 2011 (Burian & Martinů),

and 1 July 2011 (Martinu), Muziekgebouw aan ’t IJ, Amsterdam; 4

December 2001, Doopsgezinde Singelkerk, Amsterdam (Seiber).

CHANNEL CLASSICS CCS 30611 [61:25]

CHANNEL CLASSICS CCS 30611 [61:25]

|

|

|

The Ebony Band is back, this time with a jazz programme containing

known and less familiar pieces recorded at recent live performances.

Packaged in a nicely designed foldout sleeve and with a booklet

richly illustrated with period dance-themed artworks and portraits

of the composers, this is one of those releases with a vibe

of anticipation to which you know in advance the contents of

the disc will be more than equal.

Berlin-born and bred, Stephan Wolpe’s Suite from the Twenties

dramatically links atonal modernist musical tendencies with

jazz style. Geert van Keulen’s distinctive instrumentation heightens

this sometimes grotesquely theatrical effect in six punchy movements,

taking the music beyond what were originally pieces for piano

into a kind of distortion of the dance hall. This is a marvellous

piece, filled with striking and compact directness of expression.

Stravinsky-like syncopations can be heard in the opening Tango

for Irma, there is perhaps something of Kurt Weill’s declamatory

style in the Marsch nr.1, and the spirit of Webern seems

to inhabit the tonal and timbral pointillism of Tanz (Charleston).

Emil Burian was a pupil of Suk and Foerster, working for cabaret

theatres and promoting contemporary music as well as composing.

His Suite Americaine is distinctive not least for its

prominent part for the violophone, a violin whose strings are

amplified via a horn rather than the wood of a soundboard. This

strange sound floats above the band like a soloist whose part

is being sent in via radio relay and projected through an old

gramophone player. The music itself is the composer’s sophisticated

take on dance numbers like the Charlstonette (Foxtrott) and

a Valse Boston. The spooky nature of the instrumentation

is heavily in evidence in the restrained Tango Argentino,

and the final Fuga-Fox is a miniature tour de force on

the initials of the composer’s own name.

Bohuslav Martinů’s Jazz Suite has appeared a few

times in recordings, and I first came across it via a Supraphon

LP recording which can now be found on CD on a release titled

‘Works Inspired by Jazz and Sport.’ The Ebony Band’s performance

is every bit as idiomatic as the Prague players, and with more

soulful atmosphere in the Blues. The strings are more

prominent in the mix, and accompanying ostinati and sustained

notes intrude perhaps a bit much here and there, but this is

still a cracking recording. It has plenty of that loungy salon

atmosphere in the Boston and all of those subtly swinging

rhythms perfectly placed throughout, and notably in the rousing

Finale.

The Hungarian Mátyás Seiber is perhaps best known for film scores

such as that for the 1954 animated version of George Orwell’s

Animal Farm. The two Jazzolettes cross witty wah-wah

playing with Second Viennese School compositional techniques

– the second of the pieces starting with a 12-note row in the

trumpet. This is a remarkable pair of works: brief and intense,

but full of superb invention and a gasping sense of ‘how does

he do that?’

There can be little doubt that Darius Milhaud’s La création

du monde is the best known work here, and by chance I recently

had the privilege of reviewing the composer’s own conducted

recording on the André Charlin label, SLC 17. The Ebony Band

is a better bunch of players than the orchestra Milhaud worked

with in 1956, but it’s always fascinating to hear a composer’s

own rendition of his work. The timings between the versions

differs by 20 seconds, and therefore as close as makes no difference.

Werner Herbers creates an almost menacing atmosphere in the

opening pages, with heavy drums and emphasising the darker side

of the harmonies, as well as providing a fruitily warm bed of

sonority for the saxophone solo. This is a work for ballet,

so fits in with the ‘dance’ theme of this album while differing

in its lack of direct reference to dancehall numbers. As African

‘primitivism’ had already hit Paris and Picasso’s fascination

with African masks had been launched in previous years, so was

Milhaud enthralled by the black operettas he saw in New York,

integrating their fashionable American orchestration into the

story of creation as taken from African mythology. This is a

terrific piece and a marvellous performance – art and music

united in sound.

You may or may not know it, but we all really need the Ebony

Band. Werner Herbers’ crusade to make us aware of forgotten

composers and neglected repertoire has already brought us Józef

Koffler and Konstanty Regamy (see review),

Weill, Toch and Schulhoff (see review)

and many more, and once you’ve widened your horizons with these

kinds of programmes you will wonder why everyone else seems

so keen to re-record mainstream warhorses over and over again.

This Dancing – The Jazzfever of… release is taken from

live recordings at various locations, but there are no discomfortingly

extreme changes of recorded perspective, and applause and audience

noise is absent. We’ve had popular ‘jazz’ discs before now –

the kind like Simon Rattle’s London Sinfonietta EMI release

way back in 1987, which always sell out in advance of Christmas

and have shop owners tearing their hair out wishing they’d ordered

more. Let’s hope this Ebony Band achieves the same kind of commercial

success – it most certainly deserves it.

Dominy Clements

|

|

All Nimbus reviews

All Nimbus reviews