|

|

|

alternatively

CD: MDT

AmazonUK

AmazonUS

|

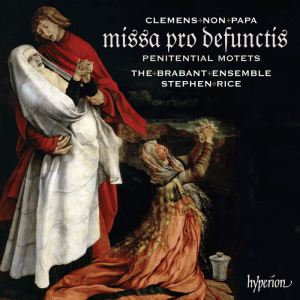

Jacobus CLEMENS non Papa

(1510/1515-1555/6)

Missa Pro Defunctis [20.38]

Tristitia et anxietas [10.02]

Vae tibi Babylon et Syria [4.59]

Erravi sicut ovis a 5 [7.29]

De profundis [9.21]

Vox in Rama [4.16]

Peccantem me quotidie [8.41]

Heu mihi, Domine [7.23]

Brabant Ensemble (Helen Ashby, Kate Ashby, Alison Coldstream (soprano);

Emma Ashby, Sarah Coatsworth, Claire Eadington, Fiona Rogers (alto);

Alastair Carey, Andrew McAnerney (tenor); Paul Charrier, Jon Stainsby,

David Stuart (bass))/Stephen Rice

Brabant Ensemble (Helen Ashby, Kate Ashby, Alison Coldstream (soprano);

Emma Ashby, Sarah Coatsworth, Claire Eadington, Fiona Rogers (alto);

Alastair Carey, Andrew McAnerney (tenor); Paul Charrier, Jon Stainsby,

David Stuart (bass))/Stephen Rice

rec. 16-18 March 2010, Merton College, Oxford

HYPERION CDA67848 [72.52]

HYPERION CDA67848 [72.52]

Sound

Samples

|

|

|

I have waxed lyrical before about the wonderful Brabant Ensemble

when reviewing their discs of Dominique Phinot (CDA67696)

and Morales (CDA67694).

This disc has not disappointed me.

I am not going to go into all that gobbledygook about why Clemens

has such a silly name or give you much in the way of biography.

I simply want to express how and why this music and these performances

have affected me so much emotionally.

Clemens has not been often recorded and when he has been the

CDs have not made much impression. The possible exception is

that by The Tallis Scholars (Missa Pastores quidnam vidistis

on Gimell 013). As Stephen Rice comments in his excellent and

extensive booklet notes, no one can be quite sure why . The

counterpoint to quote him has “points woven together …

which seem more to support the melodic line … designed

to emphasize the melodic gesture rather than to subsume it.”

It is the glorious melody which one notices first. Then come

the subtle and long lines and the sequential writing is almost

as grand as on an architectural level. Yet there is an austerity

too as exemplified most certainly by the Missa Pro defunctis

which is the longest work here. It’s not one you might

think would attract a large number of listeners to Clemens’

style, but it did me. As the motets also sucked me in I had

nowhere to hide.

OK I was listening to this penitential music during Holy Week,

sometimes in the car sometimes quietly at night. OK we were

driving about Belgium and Holland (Clemens’ homeland)

seeing the many and imposing churches, which were often austerely

clad and grimly silent, suitable for the season. In Ghent we

saw Nicholas and St.Bavo, also in Tournai, Ocquier and others

but there was more to admiring this disc than just the inspiring

atmosphere of our travels.

Stephen Rice makes decisions early on about what he thinks the

music is saying and how he sees it developing. He works at it,

obviously pointing the climaxes and the subtle word-painting

and always working with aim and direction. He is not content

simply to wallow in the wonderful melodic lines and rich harmonies.

There are several good examples. In Vae tibi Babylon et Syria

he spots the long extended development of one line which exhorts

the people to “wrap yourselves in sackcloth”. Further

on he draws attention to the subdued and plangent “and

weep for your children”. By realizing what the composer

is doing he sets his singers on course to bring out the fullest

expression as the music demands. He also deduces a later “reduction

of tension” and allows the dynamics and passion to be

gradually spent in a final passage, which “creates a sense

of exhausted despair”. In Tristitia et anxietas

he highlights the words ‘vae mihi’ (Woe unto me)

as it stands apart with block chords high in the choir’s

range and allows the “waterfall” climax of its final

bars to contrast strongly with its previous homophonic texture.

Rice also talks of Clemens’ use of sonority; that is the

use of textures which have no or little use in regard to the

text. You hear this in the De profundis setting with

its gentle and overlapping syncopations and melodies.

Clemens lived, it is said, a somewhat debauched life; at least

at times. His biography is probably in his music and this may

well have helped him to express his sorrow and regret in a strongly

confessional way in these texts. In Peccantem me quotidie

(‘Sinning every day and not repenting, the fear of death

troubles me’) Clemens focuses on, to quote Rice again

“text expressive manoeuvres” especially in the section

‘For in hell’ with its passionate descending sequence.

Rice allows the voices to drain out onto the next line, “there

is no redemption”. Also what about the final motet Heu

mihi, Domine (‘Alas for I have sinned greatly in my

life’) with its constant and seemingly endless repetitions

of ‘Quid faciam miser’ - What shall I do, miserable?

This is truly astonishing stuff.

The photograph of the choir shows eleven voices but twelve are

listed. Often it is just two to a part, but being closely recorded

and with synchronized breathing there is little sense of strained

effort. The voice quality right across whichever combination

Rice chooses to use is consistent. In addition Merton College

is about the most perfect acoustic in which to make any recording

of choral music.

I took my portable player into the Romanesque church at Bonneville

a short way south of Brussels. With the sun effortlessly cascading

through the shimmering coloured glass, I listened to the Missa

Pro defunctis. Its affecting simplicity so suited the architecture

that I listened with tears in my eyes. The usual seven movements

included as a Tractus ‘Absolve, Domine’. It’s

often homophonic and emphasises the melodic line. This is restricted

in range and never allows itself to be let loose as in the motets,

I really did begin to feel that Jacobus Clemens is as Rice states

right at the start of his notes “one of the most remarkable

composers of the sixteenth century”. There can be little

doubt that he can be considered up there with the very best.

Gary Higginson

|

|

All Nimbus reviews

All Nimbus reviews