|

|

|

MDT

AmazonUK

AmazonUS

|

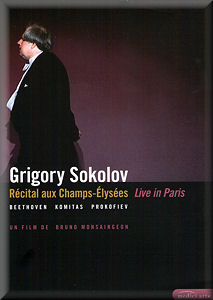

Grigory Sokolov - Live in Paris

Ludwig van BEETHOVEN (1770-1827)

Piano Sonatas: No. 9 in E, Op. 14/1 (1798) [15:00]; No. 10 in G,

Op. 14/2 (1799) [15:30]; No. 15 in D, Op. 28, “Pastorale” (1801)

[29:09]

KOMITAS (1869-1935)

Six Dances [21:53]

Sergei PROKOFIEV (1891-1953)

Piano Sonata No. 7 in B flat, Op. 83 (1942) [21:29].

Encores

Frédéric CHOPIN (1810-1849)

Mazurkas – C sharp minor, Op. 63/3 [3:23]; F minor, Op. 68/4 [4:40].

François COUPERIN (1668-1733)

Le Tic-Toc Choc ou Les Maillotins [3:21]

Soeur Monique [4:01]

Johann Sebastian BACH (1685-1750)

Prelude in B minor (after BWV855a, arr. Siloti) [2:49]

Grigory Sokolov (piano)

Grigory Sokolov (piano)

rec. live, Théâtre des Champs-Elysées, 4 November 2002

MEDICI ARTS 3073888 [123:02]

MEDICI ARTS 3073888 [123:02]

|

|

|

This is a rare opportunity to savour the art of Grigory Sokolov,

that most reclusive of pianists. A Barbican

recital in May 2006 furnished the only opportunity I personally

have had of hearing him – and what a revelation it was, too.

The trio of Beethoven Sonatas is perfectly chosen: the Op. 14

set complements the Op. 28 perfectly. How many amateur pianists,

I wonder, have slaved over the E-Major from Op. 14, aiming at

full evenness in the interlocking third semiquavers in the first

movement and, like myself, failed miserably – at least in comparison

to Sokolov. There is an element of rescuing these sonatas from

an undeserved reputation as teaching pieces so that they can

take their rightful place as a part of the canon. Sokolov lavishes

much love on the first movement of the E-Major. The central

Allegretto movement of the sonata is no mere dashed-off interlude.

It, too, has care upon care heaped upon it, to revelatory effect.

Note the way Sokolov links the two-octave leaps between the

“E”s in a miraculous way, or the way his scales are things of

pearly, even beauty in the finale. The second sonata of the

pair, the G-Major, here holds a first movement of the utmost

burnished lyricism. Bruno Monsaingeon's camera angles, fully

entwined with the music itself, and Sokolov's beloved low lighting

highlight the sense of intimacy here. Sokolov's touch in the

central movement of the G-Major is infinitely varied, his depth

of sound entirely in keeping with his conception and used to

contrast with the most fantastical staccatos. Sokolov now takes

my first recommendation in these pieces - previously reserved

for Backhaus.

The serenity of Beethovenian D-Major pervades the first movement

of Sokolov's “Pastorale” sonata. The Andante is a lesson in

fine piano technique, with the wonderfully legato right hand

against perfectly judged left hand staccati resulting in a magnificent

Beethoven processional. Musicality is all here – it is only

in retrospect that one allows oneself the time to gawp at Sokolov's

even left hand in the third movement. At the time, one is completely

engrossed in Beethoven's fascinating musical surface. And that,

surely, is how it should be. The finale is slower than most

– more a recollection of shepherds piping than the pipes themselves.

Ashkenazy in his early Decca account was most definitely in

the opposing latter camp, for example. The coda is stunning,

and, for once, not a mad romp to the finishing line.

The cheers that greet Sokolov after the final Beethoven Sonata

are more those that one would associate with end of recital

delirium. Quite rightly, though. This is Beethoven playing of

the very first rank. Every note, every phrase is to be cherished.

Not only that, Sokolov's realisation of and delineation of musical

structure is exemplary and he is one of the few musicians that

can marry that to exquisite surface detail.

The three Beethoven Sonatas provided the first half of the recital

and were given without a break for applause. The second part

opened with the Komitas Dances, an idiosyncratic choice in which

Sokolov fully presented the inherent melancholy of these pieces

from Armenia. Close-up shots of Sokolov's face show his clear

involvement and concentration. The piano is perfectly tuned

– the overall result is mesmerising.

For the Prokofiev Seventh Sonata, it is Pollini who has for

long held my affections (DG). Sokolov matches Pollini in animalistic,

elemental ferocity but includes more moments of bitter-sweet

lyricism. Again, this reading goes to the top of my tree. Sokolov's

mastery of staccato comes into its own here. Note also how Monsaingeon's

use of a distant camera can emphasise the loneliness of this

music's slower portions. The intensity of the slow movement's

climax is monumental. If Sokolov does not quite equal Polini's

cumulative effect in the finale, it is a close thing indeed.

The standing ovation is no surprise – neither is the quantity

and quality of the encores. The Chopin Mazurkas actually sandwich

the Couperin items. Sokolov's Chopin is twilit magic, his Couperin

a ray of adroitly-turned daylight. The final encore is a Bach/Siloti

Prelude. Sokolov's articulation is perfectly clean, but it is

the serenity that makes the performance glow that is most memorable.

The perfect way to end.

Colin Clarke

|

|