|

|

|

alternatively

CD: MDT

AmazonUK

AmazonUS

Downloads available from eclassical.com |

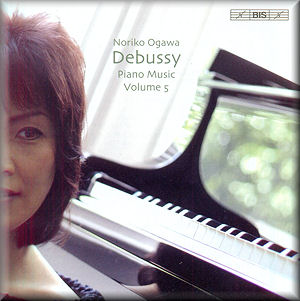

Claude DEBUSSY (1862-1918)

Piano Music - Volume 5

2 Arabesques (1890-1) [8:56], Danse (Tarentelle styrienne) (1890)

[5:09], Ballade(1890) [7:26], Valse romantique (1890) [3:22], Rêverie

(1890) [5:02], Suite Bergamasque (1890-1905) [18:04], Mazurka (1890)

[2:55], Nocturne (1892) [6:21], Danse bohémienne (1880) [2:08],

Pour le Piano (1894-1901) [14:20]

Noriko Ogawa (piano)

Noriko Ogawa (piano)

rec. Nybrokajen 11, Stockholm, Sweden, January 2000

BIS-CD-1405 [75:08]

BIS-CD-1405 [75:08]

|

|

|

I have suggested several times that the Debussy piano music

cycles by Ogawa and Bavouzet (Chandos) are the most significant

of recent surveys. The Bavouzet has been fairly speedy in its

erection. Begun in 2006 it is now complete, maybe more than

complete since the latest volume embraced piano transcriptions

of some orchestral works. If Bavouzet intends to pursue this

path he may have several more volumes in store. Nevertheless,

as far as original piano music is concerned his series is finished.

Ogawa has built up her cycle much more slowly and patiently.

Volume I, with much praised versions of the “Estampes” and “Images”,

was set down in 2000. Succeeding volumes followed at two- or

three-yearly intervals. The most recent, until now, was a really

magnificent set of the “Etudes” (Vol. IV). Though Ogawa presumably

doesn’t intend to delve into orchestral transcriptions she has

nevertheless included several items – the two-hand version of

the “Epigraphes antiques”, an enthralling performance of “La

Boîte à joujoux” and some smaller pieces – which did not appear

in earlier “canonical” cycles by Gieseking, Casadesus and others.

Here, then, is her final volume, following the previous one

at a due interval.

So it is surprising to say the least to discover that this last

volume had existed all along. It was set down a few months before

Vol. I and has been sitting unreleased for eleven years. BIS

have explained to MusicWeb that, since Ogawa’s second

sessions contained more substantial music, the decision was

made to put this first disc on hold, record all the later works

and then bring out the present CD of Debussy’s earlier

pieces as the concluding volume. This would have been OK if

the entire process had taken place over two or three years,

but Ogawa is still a fairly young artist who has surely matured

in the meantime. I would like to hear how she plays this music

now.

But let me start by saying that this may well be the most beautiful

Debussy disc in my collection. Ogawa’s sound is always limpid,

her textures transparent, her phrasing natural and musical,

her tempi unhurried but backed up by a superb sense of rhythm.

I listened first to the “Suite Bergamasque” and could only wonder,

in the “Prélude”, at how naturally she applies quite generous

rubato without distorting either the line or the rhythmic motion.

Debussy actually marked this piece “tempo rubato” and performers

tend to divide between those who pull the music out of shape

in their attempt to obey the instruction, and those who go prim

and straight. Ogawa has the secret of it. Her “Menuet” and her

“Passepied” are taken very gently, but with a rhythmic lilt

that makes you smile. “Clair de lune” is played with real feeling

yet free of romantic excess.

If I had begun at the beginning, though, with the first “Arabesque”,

I might have had a few doubts. It’s certainly a very beautiful

performance, the music flows gently and naturally from her fingers.

But it is unusually slow and a little placid. At this point

I turned to Bavouzet. He is quite a bit faster, but his actual

sound is no less translucent and the music floats as if on air.

In truth, Debussy marked this piece “Andantino con moto”. To

my ears Bavouzet’s tempo is Allegretto while Ogawa’s is a full

Andante. So maybe the right tempo is in the middle, but of the

two I prefer Bavouzet.

The tables turn in the second “Arabesque”, though. The clarity

and evenness of Ogawa’s triplets is marvellous pianism in itself,

but above all she uses her slower tempo to bring out the cheeky

humour of the piece. Bavouzet by contrast sounds as if he has

a train to catch.

The other piece about which I had some doubt is the “Ballade”.

This, like the first “Arabesque”, is marked “Andantino con moto”

and here, too, while on a phrase-by-phrase basis I admired the

sheer beauty of Ogawa’s slow unfolding, she does little to disguise

the sectional construction of the music, as a more ardent rendering

can do to some extent. On the other hand, she is ravishing in

the stronger slow pieces, the “Rêverie” and the “Nocturne”.

But so, frankly, is Bavouzet. She is magical in the “Tarentelle

styrienne” and scores notable successes with the “Valse romantique”

and the “Mazurka”. Every time a record of Debussy’s early pieces

heaves in sight my heart sinks at the thought I have to listen

to these two again. Ogawa’s graceful elegance has won me over

at last. I might even listen to them again for sheer pleasure.

The pay-off of the “Mazurka” shows she can be bold when needs

be and she’s quite cheeky with the “Danse bohémienne”.

And lastly, the most mature work here, “Pour le piano”, often

interpreted in a dry neo-classical light. Ogawa’s pianism is

all about colours. While Bavouzet’s “Toccata” is a brilliant

display of fireworks, Ogawa’s sounds as if it has as much right

to be called “Jardins sous la pluie” as the later piece that

actually bears that name. Pure magic!

So has perfection come to an imperfect world? Well, when I started

by saying this might be the most beautiful Debussy record in

my collection, some might have detected an inherent reservation.

Whatever Keats thought, I’m not sure that beauty is truth, or

at least the only way to it. If heaven is really as full of

angels sitting on clouds and playing harps as they say, this

would surely have even a Trappist Monk longing for an unredeemed

saxophone or two. Amid so much unremitting loveliness one may

just sometimes wish for something bigger, riskier, even a little

abrasive. In short, for Bavouzet. Ungrateful sod, aren’t I?

But here we’re back to my opening point. For we are comparing

Bavouzet pretty well as he is now with Ogawa eleven years ago.

Ogawa’s superbly characterized “La Boîte à joujoux” and her

magnificent “Etudes” suggest that she might herself provide

this extra interpretative range today. So, grateful as I am

for this truly beautiful record, I wish I had been allowed to

hear it eleven years ago when it was made, and could now hear

Ogawa’s latest recording of the same music.

But there it is. As things stand Ogawa and Bavouzet offer in

any case the two essential Debussy cycles of our time. Ogawa

is unfailingly beautiful, truly poetic, Bavouzet sometimes bolder

and wider-ranging. But he can be ravishing too. On the downside,

Ogawa at her least effective can be a little placid, Bavouzet

at his can be over-assertive, even aggressive. Bavouzet also

goes in for a lot of left-hand-before-right and split chords,

which I suppose some people actually like. It’s a big drawback

for me. As the two cycles are differently coupled, there’s no

way you can get a bit of one and a bit of the other and still

have all the music without duplications. So you have to throw

in your lot completely with one or the other. Or, if you really

love Debussy, get both. And, since the “Préludes” seem to draw

out the weakest in both of them, supplement them with Gieseking

in those. If you don’t like historical sound, then Thiollier’s

“Préludes” (Naxos) are the high point of an uneven cycle and

offer a plausible reproduction of Gieseking’s volubility in

modern sound.

Christopher Howell

|

|