MusicWeb interviews with Maestro Serebrier: Ann

Ozorio Gavin

Dixon

Glazunov has been one of my favourite composers since the days

of hearing broadcasts of the Fifth Symphony by the BBC Northern,

relays of the EMI-Melodiya Nathan Rakhlin Fourth Symphony (HMV

Melodiya ASD 3238), Boris Khaikin’s The Seasons (ASD2522

- in the 1970s a regular on the Radio 3 morning strand) and

Jose Sivo’s Violin Concerto (Decca SXL6532 but now on HDCD).

With this in the background I have wanted to review this set

as a complete sequence since first hearing Serebrier’s spine-tingling

version of the Fourth Symphony – of which more later.

Alexander Glazunov was a child prodigy of sixteen when his first

symphony was performed. José Serebrier was the same age when

Leopold Stokowski premiered his first symphony as a last-minute

replacement for the Ives Fourth Symphony. It can be heard on

the Guild

label. Stokowski and Serebrier collaborated over the pioneering

recording of the Ives Fourth for CBS

in the mid-1960s and, in another act of symmetry, Serebrier

later went on to record it himself for RCA.

With the fifth release in this series Warner and Serebrier complete

their cycle of the nine Glazunov symphonies. The conductor’s

account of the project and his perspectives on Glazunov can

be read in detail in a fascinating interview by Gavin

Dixon. Serebrier tell us that Glazunov is a composer close

to his heart. I can well believe that. As much can be heard

in these recordings. The conductor goes on to say that Glazunov’s

music has been neglected in part because “some performers have

played it rather "literally", without reading what's

behind the notes. If played metronomically and without emotion,

the music can sound uninteresting. It requires passion and subtlety.”

You can hear Serebrier’s approach in its quintessence in the

first two movements of the Fifth Symphony. In the first he builds

tension and exposes structural cogency through mercurial spontaneity.

It strikes me as instinctive but I am sure there is more to

it than that. Hearing Glazunov from a non-simpatico conductor

is like experiencing a flat and tepid wine designed to be enjoyed

chilled and sparkling. A Glazunov Scherzo is a thing of wonder

and Serebrier finds the mot juste in the Fifth. He unleashes

a reeling kinetic excitement in the finale making links with

Rachmaninov forwards and retrospectively with his teacher Rimsky-Korsakov.

On the same disc as No. 5 comes the ballet, The Seasons.

It’s one his most Tchaikovskian works yet in Serebrier’s hands

escapes any suggestion of being a warmed-over Swan Lake or

Nutcracker. Ice and Hail from Winter

are most touchingly pointed up making the notes leap to

attention off the pages of the score. Warner is to be congratulated

on separately tracking each section within each of the four

seasons. The great curvaceous melody of Spring is most

sensitively wielded though perhaps a notch down from Ivanov.

The Coda from Summer sheerly flies yet does not

become a gabble. If you enjoy your Tchaikovsky ballets do not

miss out on this version of the Glazunov – winning ideas tumble

one after the other.

I owe it to Ann Ozorio that I heard the first disc in the cycle.

At one of Len Mullenger’s earliest MWI reviewer get-togethers

at Keresley just outside Coventry she passed me a review copy

which she had received after her interview with Serebrier. I

have long been a Glazunov admirer and played the disc on the

2 hour plus journey back to the North-West. It is the recording

of the Fourth Symphony to have. Serebrier’s hesitations and

pressings-forward are just superbly judged, nudged and weighted.

You can hear and know that within the first three minutes

of the first movement. It’s the same in the finale with a belting

acceleration from reflective to exuberant and impetuous. Serebrier

treats the Symphony with a sort of loving respect which eschews

self-indulgence. The oboe’s song at 4:21 in the first movement

and its expressive twists and turns at 6:08 have never sounded

this good - not since the Rakhlin Melodiya recording. At the

other extreme Jacques Rachmilovitch and the Santa Cecilia Orchestra

in an ancient 1950s recording usefully revived by Pristine is

just too much of a breathless sprint. Serebrier’s unerring judgment

for pacing sweeps all before it in the finale of this glorious

symphony.

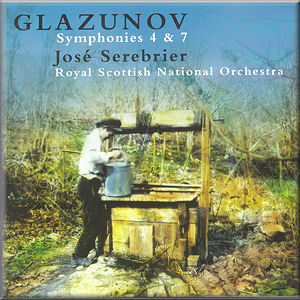

The Seventh is more relaxed as its title might suggest. It bubbles

and lilts delightfully but although Serebrier gives it some

steel especially in the Andante (II) and the Scherzo (those

gruffly accented brass and timps accents at 2:05) this is clearly

a work with a shade less tension than its disc-mate, the Fourth.

I listened to the Scherzo in the hands of Golovanov in his circa

1950 version with the Soviet State Radio Orchestra. Serebrier

works from the same book but here what is shown up is the superiority

of the RSNO wind principals who never lose definition in quite

the way that the Soviet orchestra counterparts do under Golovanov’s

typically wilful incitement. I also listened to Rozhdestvensky

giving the symphony an outing on Olympia OCD100 with the USSR

Ministry of Culture Symphony Orchestra. He is nowhere near as

tense as Serebrier and Golovanov and although he is recorded

finely the effect does not work as well as either of the other

two interpreters.

I always rather liked the Eighth Symphony even if it has come

in for some stick in various quarters. It was his last completed

symphony. My impressions and expectations were shaped by the

Svetlanov EMI-Melodiya LP – a rousing version. Glazunov comes

away with a truly sumptuous theme at 3:01 (I) and even if it

is given treatments that are redolent of Tchaikovsky and Rachmaninov

it works superbly. I an usually allergic to fugal writing but

the Elgarian cauldron whipped up at 2:30 and again and again

later in the finale is irresistibly heroic. Same goes for those

high-striding horns at 8:01 and the tramping indefatigable energy

of the last pages. The resonant qualities of the Henry Wood

Hall also play their part.

I find the delights of Raymonda rather wan after such

intensity; perhaps Warners should have reversed the order of

the works on the CD. In any event it is charming stuff even

if not up to the standards of The Seasons. The glowing

Soir, Clair de Lune (tr. 10) stands above the general

mêlée here as does the fine Valse Fantastique.

The Sixth Symphony is as Andrew Huth - who writes the informative

liner essays for most of the series - says in his notes the

one closest in style to Tchaikovsky. It at first wears its tragedy

heavily and recalls the Pathétique in the first movement.

Glazunov could never resist a Scherzo and he did them very well.

This one is a shade more deliberate than its counterparts in

the flanking symphonies. The finale has the iron-shod tramping

power of the finale of the Rachmaninov First Symphony finale

a work which Glazunov was infamously to conduct a month after

he conducted the premiere of his own Sixth. His tone poem The

Sea was written when the composer was in his twenties. It

is a pleasingly stormy romantic work which after the tempests

revels in a lighter lyric mood. It ends in what seems night-scene

in which the sea glimmers poetically in the moonlight. The scene

closes but not before a final macabre shudder from the depths.

It is usually pigeonholed alongside his other atmospheric pictorial

poems: The Kremlin (1890), The Forest (1887) and

Oriental Rhapsody (1889). The richly romantic Salome

music written in 1907 for a St Petersburg production of

the Oscar Wilde play ends the disc.

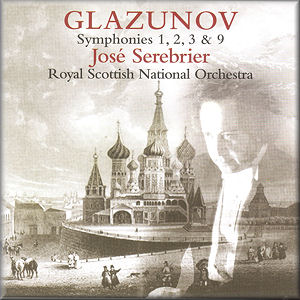

The last volume to be issued was a two disc set. Hearing the

long gait of the Third Symphony’s first movement reminded me

how the composer had, over the twenty year period spanned by

the eight symphonies, held true to Russian nationalist style.

It remains very enjoyable and full of the eager effervescence

of invention. The style is closer to that of his teacher Rimsky-Korsakov

but the pleasures are no less even if extended across 48 minutes

and his usual four movements. It’s the longest of his symphonies.

The incomplete Ninth was left in piano score and passed to a

cousin of the pianist Mariya Yudina who orchestrated the single

movement from piano score in 1947-48, twelve years after Glazunov’s

death. It has an Elgarian nobilmente about it and not

unsurprisingly seems to be from the same notebook as the finale

of the Eighth.

The Second Symphony is five minutes shorter. It was premiered

by the composer at the 1889 World Exhibition in Paris. The lugubriously

romantic second movement for me recalls the Balakirev First

Symphony. The finale is superbly rendered by the Warner engineers

and the artists with plenty of antiphonal detailing.

We end with the enjoyable First Symphony. This too is in the

accustomed four movements with several moments particularly

reminiscent again of Rimsky and of Borodin’s Prince Igor.

It will be recalled that Glazunov assisted with the completion

of Borodin’s Third Symphony. The invention is a step down from

the finest symphonies and the finale occasionally succumbs to

bombast but what is here is enjoyable and well worth discovering.

It is after all the work of a sixteen year old – the same age

as his pupil Shostakovich when he wrote his own First Symphony.

Over the years there have been several recorded cycles of the

symphonies. There’s rather good one from Rozhdestvensky (once

available complete and slip-cased on Olympia OCD5001). Then

again there’s Järvi’s 1980s on Orfeo (not reviewed here unfortunately).

Otaka recorded the eight symphonies for Bis.

Polyansky recorded most of them for Chandos and many of these

alongside some from Yondani Butt (ASV) and Otaka (Bis) found

their way into a bargain-priced set from Brilliant

Classics. Even the long-lost Fedoseyev Soviet (Moscow Radio

Symphony Orchestra) set can be had as an mp3 download via Amazon

for as little as £5.99. Though not without merit the least attractive

and sadly torpid cycle of the symphonies came from Naxos (Anissimov

review

review)

although no company has recorded as much Glazunov. Svetlanov’s

fine but long inaccessible set can now be had in a SVET box

(review

symphonies; review

orchestral works).

The Brilliant box is inexpensive and deploys mostly Chandos

sound quality. It’s pretty good though Polyansky can hit patches

of lassitude. The Svetlanov box can be difficult to source but

may be too old-sounding, raw and invigorating for some ears.

Even with all that heritage, Serebrier and Warner have the finest

modern premium price cycle available. It combines consistently

inspired interpretative insights, Imperial Russian style and

superb audio-technology.

In the Gavin Dixon interview there is talk of the complete Glazunov

concertos. After the exalted results secured here I hope that

comes to pass.

Rob Barnett

The Glazunov symphonies conducted by José Serebrier on Warner

Classics

Alexander

GLAZUNOV (1865-1936)

Alexander

GLAZUNOV (1865-1936)

Symphony No. 6 in C minor op. 58 (1896) [35:51]

The Sea - Fantasy in E major op.28 (1890) [15:22]

Salome - Introduction and Dance op.90 (1908) [15:19]

Royal Scottish National Orchestra/José Serebrier

rec. 4-6 June 2008, Henry Wood Hall, Glasgow. DDD

WARNER CLASSICS 2564 69627-0 [66:48]

Alexander

GLAZUNOV (1865-1936)

Alexander

GLAZUNOV (1865-1936)

Symphony No. 4 in E flat major op. 48 (1893) [33:31]

Symphony No. 7 in F major op. 77 Pastoral (1902) [36:21]

Royal Scottish National Orchestra/José Serebrier rec. 28 February-2

March 2006, Henry Wood Hall, Glasgow. DDD

WARNER CLASSICS 2564 63236-2 [69:52]

Alexander

GLAZUNOV (1865-1936)

Alexander

GLAZUNOV (1865-1936)

Symphony No. 5 in B flat major op. 55 (1895) [32:36]

The Seasons - ballet in one act - op. 67 (1901) [36:38]

Royal Scottish National Orchestra/José Serebrier

rec. 2-5 January 2004, Henry Wood Hall, Glasgow. DDD

WARNER CLASSICS 2564 61434-2 [70:31]

Alexander

GLAZUNOV (1865-1936)

Alexander

GLAZUNOV (1865-1936)

Symphony No. 8 in E flat major op. 83 (1905) [42:28]

Raymonda - suite from the ballet op. 57a (1898) [36:42]

Royal Scottish National Orchestra/José Serebrier

rec. 9-11 January 2005, Henry Wood Hall, Glasgow. DDD

WARNER CLASSICS 2564 61939-2 [78:50]

Alexander

GLAZUNOV (1865-1936)

Alexander

GLAZUNOV (1865-1936)

CD 1

Symphony No. 3 in D major, op. 33 (1890-92) [48:12]

Symphony No. 9 in D major, Unfinished orch. Gavriil Yudin

(1909) [10:32]

CD 2

Symphony No. 2 in F sharp minor, op. 16 (1886) [43:22]

Symphony No. 1 in E major, op. 5, Slavyanskaya (1881)

[34:17]

Royal Scottish National Orchestra/José Serebrier

rec. Henry Wood Hall, Glasgow, 2-5 June 2009. DDD

WARNER CLASSICS 2564 68904-2 [58:44 + 77:39]