Tovey's 'The Bride of Dionysus'

A dream come true

Peter R. Shore

See also

Sir

Donald Francis Tovey (1875–1940) by Peter R. Shore

TOVEY's THE BRIDE OF DIONYSUS

Synopsis

with musical examples

Donald Francis Tovey (1875- 1940), Reid Professor and Dean of

the Faculty of Music at Edinburgh University from 1914 until

his death, was my paternal grandmother's first cousin. Although

Tovey is best known for his Essays in Musical Analysis he was

a noted concert pianist and also composed symphonic as well

as chamber music. Among his work is an opera called The Bride

of Dionysus to a libretto by Robert Calverley Trevelyan.

The opera was produced by the Edinburgh Opera Company in 1929

and again in 1932 and conducted by the composer himself. Having

read a biography of Tovey in 1990 (by Mary Grierson, published

in 1952 by OUP) my curiosity about the opera got the better

of me and after some detective work I traced the vocal score

and the full orchestral score (all 750 pages of it!) to the

Reid Music Library at Edinburgh University. The full score has

never been published and the opera has never been performed

again since 1932. In 1936 Fritz Busch wrote from Glyndebourne

asking for a pianoforte score of The Bride with which

he was already familiar. Tovey had hopes that his opera would

be performed at Glyndebourne and to this end he wrote in the

same year a letter to John Christie, the founder of Glyndebourne,

who was a personal friend. It was decided, however, that the

opera was too large for the stage requirements and too long.

Three years later in 1939, after some reconstruction of the

stage at Glyndebourne the matter was considered again, and it

was decided that the opera should be given in 1940. But with

the coming of the Second World War and Tovey's death in 1940

the project was laid to one side, never to be revived.

As I began to play laboriously through the piano/vocal score,

the piano part was written for a concert pianist which Tovey

was, I couldn't help wondering why this beautiful music had

been allowed to disappear without trace, gathering dust on the

shelves of a library.

I visited the Reid Music Library in Edinburgh to see what material,

apart from the printed piano/vocal score exited. The full handwritten

orchestral score existed as well as the hand-copied parts. But

in the biography Tovey had complained that so much of the orchestral

rehearsals had been taken up by correcting all the mistakes

in the parts. I looked through the parts and found this to be

true. So I decided the first thing to do was to transcribe everything

onto the computer using a MIDI keyboard and notation program.

Little did I know when I started transcribing the material that

it would take me ten years to complete it. I still had a full-time

job and growing family. The advantage of transcribing the opera

onto the computer using the Coda Finale notation program is

that one is able to listen and playback the material to check

for mistakes. I was to discover later that many mistakes remained

even after this process. The other advantage is that the computer

does all the work extracting the parts from the full score.

Although there is plenty of work left fixing the layout as well

as planning suitable page turns and other necessary copyist

jobs. So now I had a full score and a complete set of parts

all neatly printed out and a pretty good idea what the opera

sounded like. What next?

I realised very early on that the chances of getting a performance

of an opera which was nearly four hours long by a virtually

unknown composer were nil. I began compiling a concert performance

of approximately an hour in length, reasoning that this would

stand a much better chance. This work was put back on the shelf

while I went through the same process with Tovey's Symphony

which had never been published either.

Martin Anderson and Toccata Classics came to the rescue and

in 2005 the Symphony was recorded in Malmö, Sweden with the

Malmö Opera Orchestra conducted by George Vass (a complete

description of this recording from the producer's point

of view can be found on the MusicWeb - also

recording review).

The next project George and I tackled was Tovey's Cello Concerto

which was dedicated to and given its first performance in 1935

by Tovey's old friend Pablo Casals with Tovey conducting. The

concerto was broadcast from a concert in the Queen's Hall, London

in November 1937 with the BBC Symphony Orchestra conducted by

Sir Adrian Boult who thought highly of it. The broadcast was

recorded onto acetate disks, put onto a shelf and forgotten

about. They were discovered in 1975 when the BBC were planning

a programme on the centenary of Tovey's birth. But in the meantime

a green mould had grown on the disks and after cleaning the

disks could only be played once in order to transfer the material

onto tape. The result was of depressingly poor quality but moments

of Casals magic are still discernible. Our recording took place

in May 2006 in the Ulster Hall, Belfast with the Ulster Orchestra

with the cellist Alice Neary as soloist. Alice's husband David

Adams was the leader of the orchestra (more of David later).

We were very fortunate to have the services of recording producer

Michael Ponder who brought his years of recording experience

as well as being an excellent string player himself. We utilised

the BBC's recording facilities in the Ulster Hall as well as

their senior music engineer, John Benson. This recording was

released on the Toccata Classics label in the same year. review

It began to dawn on me that there was now a real possibility

of recording my concert version of Tovey's opera. I began discussing

this with George Vass (I could not imagine anybody else conducting

it!) and we began going through the whole opera to decide what

could be used and remain true to the plot.

The reader may be wondering why I didn't contemplate recording

the whole opera. I do not have the financial resources to record

all of it and thought that the recording we were planning was

better than nothing at all. I am prepared to be criticised for

this and offer no apology. If anyone else wishes to record (or

perform) the whole opera I am only too glad and have a full

orchestral score and a complete set of parts which they are

welcome to use.

We decided to return to Belfast and the Ulster Orchestra who

had done such a magnificent job on the cello concerto recording.

So they were contacted and recording dates were planned for

the end of May 2009. The next problem was finding the soloists.

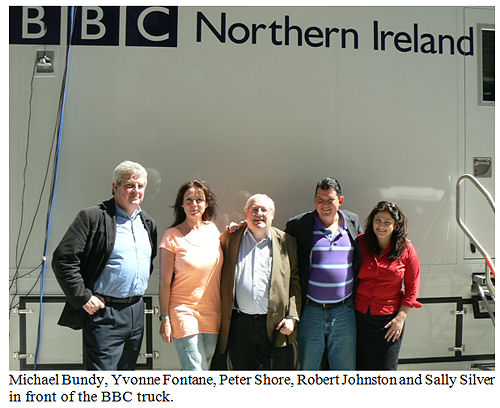

I had heard the soprano Sally Silver, originally from South

Africa, sing several years previously and decided she was the

voice of Ariadne, the daughter of King Minos. Sally was approached

and agreed to sing the role. George had worked previously with

the mezzo-soprano Yvonne Fontane who has received international

acclaim for her interpretation of Carmen and is artistic

director of amongst others the Lakeland Opera. Yvonne would

sing the role of Phaedra the younger sister of Ariadne. Robert

Johnston, the tenor and Michael Bundy, the baritone who are

both members of the BBC singers have worked with George on many

occasions and have a great deal of operatic experience. Robert

would sing the role of Theseus and Michael would sing the roles

of both King Minos and Dionysus.

The chorus is an integral part of the opera so the next problem

was finding a suitable choir. We contemplated bringing a choir

with us but decided that this was financially impossible. I

had heard both positive and negative reports of the Belfast

Philharmonic Choir. But their choir-master Christopher Bell

is well known for achieving great results. Michael Ponder was

asked back as recording producer. John Benson unfortunately

had a prior engagement but we decided to use the BBC's facilities

together with senior sound engineer Davy Neill assisted by Alex

Forsyth. Our chief engineer would be Anthony Philpot. Tony Philpot

had a long career as a senior sound supervisor at BBC TV but

has been a freelance engineer for several years. He is a church

organist and has been for over thirty years. Tony and I were

at school together and although we have kept in touch over the

years have only recently been working together. So now the team

was complete.

The soloists, George, a rehearsal pianist and I had a run-through

of the opera at a rehearsal room in London two months prior

to the recording. I then flew to Belfast to complete negotiations

with David Byers the chief executive officer of the Ulster Orchestra

and meet Davy Neill to discuss the technical requirements. Davy

was happy to have Tony Philpot at the controls and knew him

by reputation. I went along to the second rehearsal of the choir

and realised that although they had a long way to go they were

very keen to be a part of the recording and that they were in

the very capable hands of Christopher Bell.

A project of this magnitude has basically three phases. Pre-production,

production and post-production. The logistics involved require

a great deal of planning and the more thorough one is in planning

the less likelihood of problems arising and costing both time

and money. But problems are unavoidable!

We would require six three-hour sessions at least to record

all we needed and because the choir had day jobs they would

only be available at the weekend. So we started on Thursday

28th May 2009. The morning was taken up by the engineers

rigging a large quantity of microphones. The orchestral staff

were putting out all the chairs and music stands and Paul Mckinley

the orchestral librarian was busy putting all the orchestral

parts in the right place. The Ulster Hall had recently been

renovated and the paint was hardly dry. When recording the Cello

Concerto we had used the BBC control room in the Ulster Hall

but the new control room would not be ready for the opera and

so we had to use the BBC's sound truck which was parked in the

road outside the hall. An optical fibre cable with all the microphones

signals trailed through the hall and through a window to the

truck outside. The technical team managed to squeeze into the

truck with Tony at the controls of the mixing desk, Davy monitoring

everything and keeping a record of all the takes, Michael producing

and Alex making sure all the computer systems were functioning

correctly and that the material was being properly stored on

hard disks. I had decided that each microphone should be recorded

on a separate track ie multitracked. The BBC engineers are very

used to producing a stereo 2-track signal for live broadcasting

but multitracking everything gave us the option of adjusting

levels on each channel during the mixing and editing process

giving us the best possible final result.

We started recording on the Thursday afternoon with Robert

and Sally's arias and their duet. Tony quickly got a good stereo

balance which was recorded on two tracks of the multitrack and

would provide a good reference as we recorded the rest of the

opera. We reckoned on recording between 15 and 20 minutes worth

of material at each session and by the end of the session we

had recorded all the material planned.

The Friday morning session was purely orchestral and opened

with the Prelude of the opera. I had already heard this when

I recorded Tovey's Symphony in Malmö in a broadcast studio which

only just accommodated the Malmö Opera Orchestra. What a difference

hearing it again in the wonderful open acoustic of the Ulster

Hall! David Adams the orchestral leader played the solo violin

part at the end of the Prelude so beautifully and with such

feeling. Then came the orchestral opening to Act 2 which is

full of pomp and circumstance which melts away to piano in the

strings as the curtain rises to reveal the Labyrinth bathed

in moonlight where dark deeds are about to take place. Robert

and Yvonne added their parts to the next orchestral interlude

which is the death of the Minotaur. This is pure film music

and we hear Theseus running through the Labyrinth and meeting

up with the Minotaur, half bull, half man. They start fighting

and the Minotaur is fatally wounded and falls down the stairs.

Distant trumpets are heard warning Theseus of the approaching

Cretan guards and he makes his escape through the Labyrinth

to meet up with the Athenian captives who have also escaped

and are waiting for him by the shore. ”Hail friends, slain is

the Minotaur!” Theseus cries out and they make their escape

by boat from Crete.

The afternoon session was devoted to Phaedra's aria, the longest

and most difficult one in the opera. The role of Phaedra was

written for a contralto but I thought a mezzo-soprano would

give a much better result and Yvonne Fontane proved me right.

The escapees have arrived on the island of Naxos including Ariadne,

Phaedra and Theseus. Theseus is still in love with Ariadne and

Act 3 opens with Phaedra standing by a small fire using her

witchcraft to bewitch Theseus and entice him away from Ariadne.

The aria is very chromatic with many key changes and whole scales

and borders in places on the atonal with sweeping harp glissandi

to illustrate the flickering flames of the fire. Phaedra reaches

the climax of her aria with the words ”He is mine!” and Yvonne

thundered out her top A. I was sitting on the stage opposite

her and that moment the hairs on the back of my neck stood up

and I felt a tingling all down my spine. That's what music can

do for you!

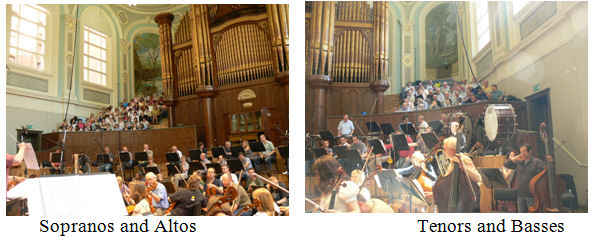

Saturday morning and the whole ensemble was gathered to record

Act 1, Scene 1 of the opera. The four soloists at the front

and the 100 strong choir who were seated behind the orchestra

in the galleries on either side of the organ. The morning session

went well and we completed the choral sections in Act 2 before

breaking for lunch. George and I had been to the last rehearsal

of the choir on the Wednesday evening and knew that we had nothing

to worry about. They had been well rehearsed by Christopher

Bell and were so enthusiastic about doing the sessions at the

weekend with the orchestra. I reminded them that we were recording

an opera and not an oratorio and I expected plenty of expression

from them. I was not disappointed!

After lunch we said goodbye to Robert and Yvonne who had completed

their parts and I was sorry to see them go as they had given

me such wonderful performances. In the afternoon we moved onto

Act 3 Scene 9. Michael Bundy now changed roles and instead of

the irascible King Minos he took on the mantle of the serene

god Dionysus. Tovey states in the score that Dionysus is the

majestic God shown on a Greek Vase, not the Bacchus of Titan.

The session went well and we took a break just before the Piu

Largamente which leads into the Finale. After the break

disaster struck! I explained at the beginning of this article

about the process of transcribing the handwritten score onto

the computer and extracting the parts. However hard one tries

and however many pairs of eyes scrutinize every page and every

part mistakes get through. Horn parts are different for historical

reasons. Before the invention of the valve in the early years

of the nineteenth century brass players, with the exception

of the trombone could only play notes of the harmonic series.

When the rest of the orchestra changed key the horn player had

to add an additional length of tubing called a crook and play

a different harmonic series to match. There was no key signature

in the horn parts only an indication to change to another crook.

When valves were introduced the horn parts retained the tradition

of having no key signature but as the player had more access

to more notes accidentals (sharps and flats) were added in front

of the notes that required them. In extracting the horn parts

of the Finale from the score the computer had left out the accidentals

and in the rush to get the parts ready I did not notice they

were missing. As we began recording the Finale a lot of very

wrong notes started come out of the horn section. Everything

ground to a halt and the leader of the horn section stood up

angrily complaining about the unprofessional behaviour of the

copyist. I replied that I took full responsibility for the mistakes

as I had done the copying and was prepared to 'face the music'.

The session came to an abrupt halt and everybody packed up and

went home. I left the hall deeply depressed and went into the

sound truck to apologise to everybody there and was on the point

of calling the whole thing off when my friend Tony Philpot took

me on one side and told me not to worry that everything would

be sorted out and we would pick up where we had left off the

following morning. George had immediately gone to talk to the

horn section to perform a public relations job on my behalf.

I returned to the hall and went up to David Adams the leader

to apologise to him. David told me to bring the horn parts and

the handwritten score and that we would sit down there and then

and correct the parts together. This is not the job of the orchestra

leader, but David is such a nice person and dedicated musician

and, as this was to be his last recording session with the Ulster

Orchestra before he took up his post as leader of the Welsh

National Opera Orchestra, he wanted it to be a success. So we

sat on the stage for next two hours and wrote in all the missing

accidentals. I then went back to the hotel which fortunately

was just across the road from the Ulster Hall and spent the

rest of the evening checking the horn parts for the whole of

the Finale.

The morning session on the Sunday was to be our last as the

hall was booked for another event in the afternoon starting

at 4 pm and the engineers and orchestral staff needed the time

to dismantle everything. I approached the horn section with

some trepidation but after checking the parts they said they

were happy to get on with the recording. I went down to the

front of the stage and sat down behind the soloist, George raised

his baton and we were off. Michael Bundy now in the guise of

Dionysus sang ”O thou pure soul, thou chosen shrine of justice

and love”, with his magnificently rich baritone voice echoing

round the hall. The choir came in with their big final chorus

”blessed art thou o bride divine”. This was their big moment

and they did not waste it and sang with such gusto. Tovey shows

his mastery of counterpoint by bringing in many of the themes

and motives which have been heard previously in the opera passing

them back and forth between orchestra and chorus with a fugue

thrown in for good measure. The orchestra builds up to a powerful

fortissimo tutti backed up by everything in the percussion department

and as the choir intone their final notes they are joined by

Ariadne's voice ringing out above them. She continues her final

aria with a rich orchestral accompaniment climbing first to

a top B flat, then a top A and finally a perfect top C which

resounds round the hall and is answered by a top C from the

trumpet. She ends her aria with the words ”with the fullness

of thy godhead made whole” and the orchestra builds up to a

final fortissimo tutti dying away as the solo violin plays the

same solo from the Prelude and the opera finishes on a D major

chord in same key as it started.

My dream had come true! Words failed me and I was completely

overcome.

Of course there was still the editing and post-production work

to be done but we were extremely lucky that Michael Dutton of

Dutton Vocalion and his A & R consultant Lewis Foreman had

agreed to release the opera on the Dutton Epoch label which

specialises in British classical music. Its out and now available

in the shops and on the Internet. I am so grateful to all those

who made my dream come true and I am well aware that without

the help of so many talented and enthusiastic people none of

this would ever have been possible. I can see Tovey sitting

on his little white cloud with a big smile across his face.

To him music was his life, his all and his compositions mattered

to him.

© Peter R. Shore 2009

photographs by Peter R. Shore

The recording - Ulster Orchestra/George Vass - Excerpts from

Tovey’s The Bride of Dionysus CDLX

7241

see also

Sir

Donald Francis Tovey (1875–1940) by Peter R. Shore

TOVEY's THE BRIDE OF DIONYSUS Synopsis

with musical examples

http://www.donaldtovey.com/